Archival Spaces 288:

William Thiele’s Downward Slide in Hollywood

Uploaded 4 February 2022

While my recent blog discussed the USC/Academy Museum’s symposium “Vienna in Hollywood,” here is an abridged version of my talk on the Austro-Jewish film director William Thiele, who will be the subject of a book I’m editing with Andréas-Benjamin Seyfert: Enchanted by Cinema: William Thiele Between Vienna, Berlin and Hollywood. Given that I interviewed William Thiele for an AFI Oral History in June 1975 – at the very beginning of my research into German-Jewish refugees to Hollywood, – my career is coming full circle.

In the 1920s and early 30s, Wilhelm Thiele became the UFA’s director of choice for light entertainment, his Drei von der Tankstelle (1930) establishing a new genre of sound film operettas, until 1933 when he was blacklisted by the Nazis for being a Jew. By 1934, Thiele was in Hollywood at Fox, and then Paramount, where he had a worldwide hit with Dorothy Lamour’s soon-to-be-famous sarong in The Jungle Princess (1936), before slipping into B-film production at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, where he made a series of delightful, family-oriented comedies with low budgets and modest but respectable yields. When Thiele’s contract was not renewed in early 1940, his career pretty much fell off a cliff. Although he had experienced periods of unemployment in Hollywood, nothing would match the ensuing eight years of unemployment, interrupted by merely three directed films for ever-lower budget producers.

Thiele’s frustration is palatable in his correspondence with the Austro-German agent Paul Kohner. Thiele had originally been signed by Stanley Bergerman who had opened a talent agency in 1936. In a letter to Kohner dated February 1939 while he was still at MGM, Thiele apologized for re-upping with Bergerman, instead of moving to Kohner who had recently opened his own agency, because he had a big family to support, including relatives still in Europe. In August 1943, Thiele made the move to Kohner, having already been unemployed for all but six weeks in 1942 and 1943, when he worked on two Tarzan films. In November 1943, Thiele writes to Kohner: “I’ve been waiting all month and not a single interview with a producer. I MUST FIND WORK RIGHT AWAY AND MUST EARN SOME MONEY.” Seven months later he writes to Kohner: “It’s ridiculous I can’t find work.” A Part of the problem may have been that even though both Tarzan films for Sol Lesser were financial successes, especially Tarzan Triumphs (1943), Thiele was fired by Sol Lesser after the second film.

Kohner tried for a year to negotiate a deal for Thiele before the director gave up on Kohner in late 1944. The agent had negotiated with a Mexican film producer, Gen. Juan Francisco Azcárate, setting up a three-picture deal that would have sent Thiele and his family to Mexico City in March 1944. The deal however fell through because the first script offered to Thiele was not a film he wanted to make. As Thiele wrote: “The story lends itself much more to a risqué farce than to the kind of musical with charm and feeling which I used to make and which proved to be so successful.” Furthermore, as Kohner noted to the producer, the story was anti-American. Azcárate did purchase a script Thiele had written with the Hungarian writer László Görög with whom he formed a writing partnership. The team sold several more scripts, including She Wouldn’t Say Yes (1945) with Rosalind Russell.

Thiele reportedly signed a long-term contract at Republic in June 1945 to make The Madonna’s Secret, starring Francis Lederer and based on a script by Thiele and Bradbury Foote. The film was an attempt by Republic to make a more serious, higher-budget product, and Thiele was congratulated for leading the effort. The film got very good reviews, nevertheless, it remained a one-off for Thiele at Republic. Thiele apparently just couldn’t catch a break.

Needing desperately to support a family, Thiele was saved by producer Jack Chertok who assigned Thiele to direct industrials and public service educationals, then transitioning to commercial television. For years, Chertok had produced short films at MGM, before forming his own company, Apex Film Corporation, in April 1945 to produce shorts, industrials, and advertising films. Thiele is listed as Apex’s staff director in the 1946 Film Daily Yearbook and remained with the company for at least ten years as a salaried employee. One early client of Apex was the National Association of Manufacturers for which Thiele directed and co-wrote the public service short, The Price of Freedom (1948). The short film follows a young newspaper reporter to Germany, where he learns that freedom of the press should not be taken for granted. The Freedoms Foundation Award winner was not only anti-Nazi but an explicit defense of free speech in the wake of the House Un-American Activities growing anti-Communist hysteria. For the U.S. Department of State Thiele directed University of California at Los Angeles (1948), for the U.S. Department of Education Junior College for Technical Trades (1950), for the Southern California Dental Association, It’s Your Health (1949), and for the National Tuberculosis Association, A Fair Chance (1954).

Thiele’s most productive association was with Apex client, I.E. Du Pont de Nemours Company of Wilmington, Delaware, for which Thiele wrote and directed three industrials about Dupont’s nylon production. Thiele was then hired to produce a feature-length, color docudrama on the history of the Dupont Company for its 85,000 employees, The Dupont Story (1950), which was ultimately also exhibited non-theatrically. Budgeted at $250,000 ($2,869,180/2021), the film presented a history of the family-owned company, featuring more than fifty Hollywood actors.

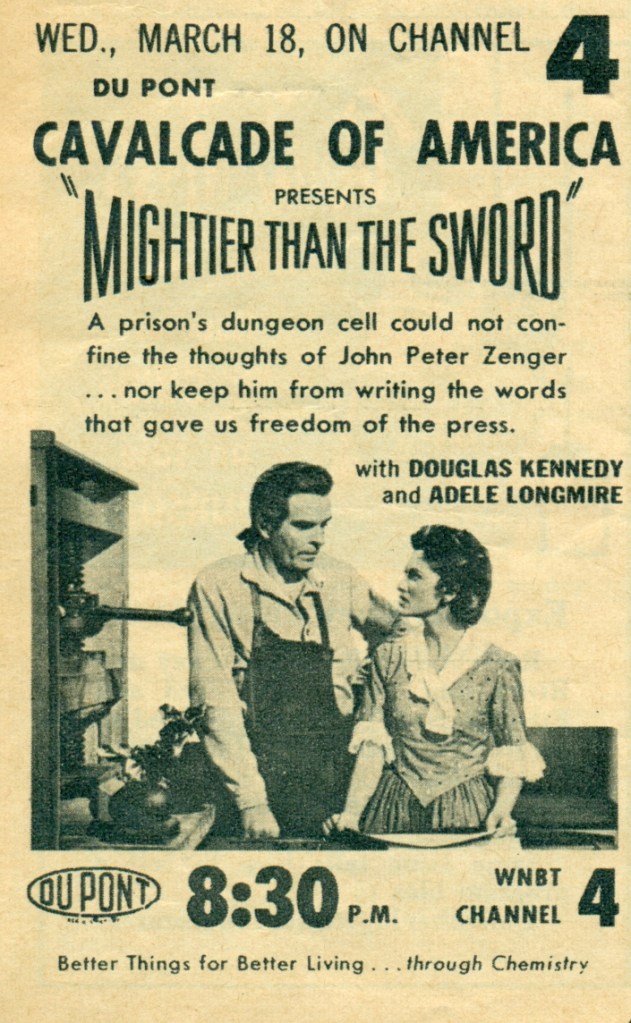

DuPont also sponsored the Apex production of the television series, Cavalcade of America (1952-1957), based on the Dupont radio show on-air since 1935 to improve their public relations image. Each episode of the half-hour show illustrated a moment in American history. Until May 1955, Thiele would go on to direct no less than thirty-five episodes, including shows about John Peter Zenger, William Penn, Benedict Arnold, Ben Franklin, John Marshall, Wyatt Earp, Horace Greely, and many lesser or unknown figures, including women Dr. Alice Walker and Elisabeth Blackwell.

Jack Chertok also contracted with General Mills to produce The Lone Ranger television series in September 1949, after Apex director Sammy Lee directed the industrial, Assignment General Mills (1949). Thiele, however, did not work on The Lone Ranger until its fourth season in 1954. He completed 25 episodes until September 1955 when the last b&w season ended and Apex lost the contract. Thiele remained unemployed for much of 1956-1958, accepting a three-picture contract with Deutsche Film Hansa and completing two films in Germany, before returning to Los Angeles and retirement at age 70 in 1961.

Surprisingly, when I interviewed Thiele so many years ago, he not only expressed no bitterness or regrets for failing to reach the heights of his European career in Hollywood but actually expressed gratitude for the good life America had given him.