Archival Spaces 292

Film Erotica in Papal Film Archives

Uploaded 1 April 2022

My wife and I have been in Rome for the past ten days. Since this is not our first trip to Rome, we have forgone most of the Roman antiquities sites, and have focused on visiting libraries, archives, and private collections of art, including the Galeria Colonna and Galeria Doria Pamphili, still owned and maintained by two of Rome’s wealthiest and most prestigious families, both of whom have been supplying Popes to the Vatican for the last five hundred years. Unfortunately, many of the city’s most famous libraries, including the Biblioteca Casanatense and the Biblioteca Angelica are closed, possibly due to COVID, but who knows, since both websites say they are open. In both cases, we were told, “Non lo so,” when asked when they will open. However, we were vey lucky to see a virtually unknown rarity in Rome’s landscape, namely the Filmoteca de la Pape, or Papal Film Archives.

Getting into the Filmoteca de la Pape, – not to be confused with the Vatican film Library – was a major undertaking and took weeks of negotiation with the Brussels office of the Federation Internationale des Archivs du Film – before we got to Rome, and finally only a letter from Archbishop José Gomez of Los Angeles got us into the facility. The reason it is so difficult to see this archive, is because it houses one of the largest collections of film erotica in the world, rivalling even the Kinsey Archives Collections. Its official name is the Filmoteca Erotica de Pape, but for obvious reasons the more neutral term is being used.

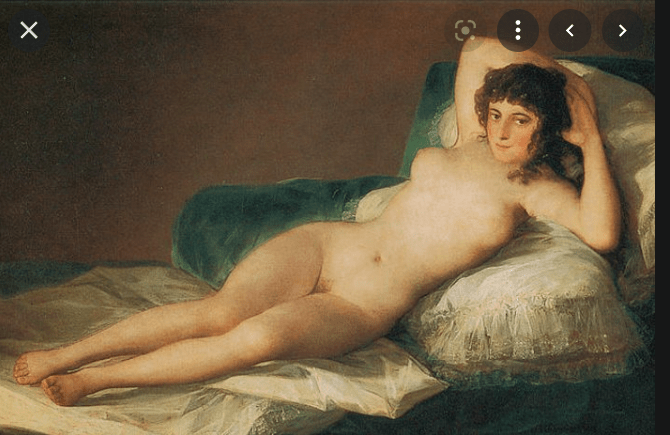

The Papal libraries have of course been secretly collecting erotic images and books since the latter stages of the Inquisition, when Francisco Goya was summoned in 1815 for having painted The Naked Maja (1805). At the time, administrators in the offices of Pope Pius VII hoped to eradicate all such visual temptations to the flesh by confiscating or purchasing whatever they could find, destroying much of it, but keeping a percentage as documentation of the devil’s work. When Pope Leo XIII was informed by a papal spy in the offices of the Archbishop of Paris, His Eminence François-Marie-Benjamin Richard de la Vergne, in 1899 that the Lumiere Brothers were distributing pornographic films under the table, along with their more famous La Sortie de l’Usine Lumière à Lyon and L’arrivée d’un train en gare de La Ciotat, papal authorities sprung into action, founding the Filmoteca de Pape as a compliment to a similar archive of pornographic photographs that had been set up in the 1850s, after profane images of naked male and female bodies began circulating. For a few years, there was a power struggle between the two archives, but eventually the Filmoteca de Pape won its independence.

Wisely, the Papal authorities decided that it would not be politic to have such an archive within the confines of the Vatican itself, so a building was purchased in a back courtyard off the Piazza de Renzi in the Vicolo del Cinque in Trastevere. While official films of the Vatican are housed in the Vatican Film Archives proper, the Filmoteca de Pape collected blue material from the turn of the twentieth century to the 1970s. As a staffer told us, the Archive gave up acquiring new material at the time, because funds had been cut and the amount of pornographic material being produced morphed into an avalanche that could no longer be contained. According to the Filmoteca de Pape’s curator – understandably they wished to remain anonymous – the earliest erotic film in the collection is Fatima’s Coochie-Coochie Dance (1896), an Edison kinetoscope film, which shows a gyrating belly dancer.

The Filmoteca’s earliest French pornographic film is A L’Ecu d’Or ou la bonne auberge / At the Golden Shield or the Good Inn from 1908, which survived in a 9.5 mm copy. Unfortunately, many of the earliest films from the turn of the 20th century no longer survive, because the Filmoteca for decades did not have climate-controlled vaults, leading to nitrate decomposition, including as paper records indicate, close to 100 films, produced in the brothels of Buenos Aires and exported to Europe to be shown at stag parties, or what the Germans called “Herrenabende.” One Argentine film that has survived is El Satario / The Satyr, which may have been produced as early as 1907.Besides the French, who specialized gay and straight porn, sometimes in the same film, the Austrians and Germans were big producers. Another gem in the collection of the Filmoteca de Pape is Am Abend, a ten minute German film from 1910.

We were hoping to actually see a few examples from their rich collection of silent porn, but unfortunately COVID restrictions did not make it possible. Their new climate-controlled vaults, however, rival any of those in Italy.