Archival Spaces 381:

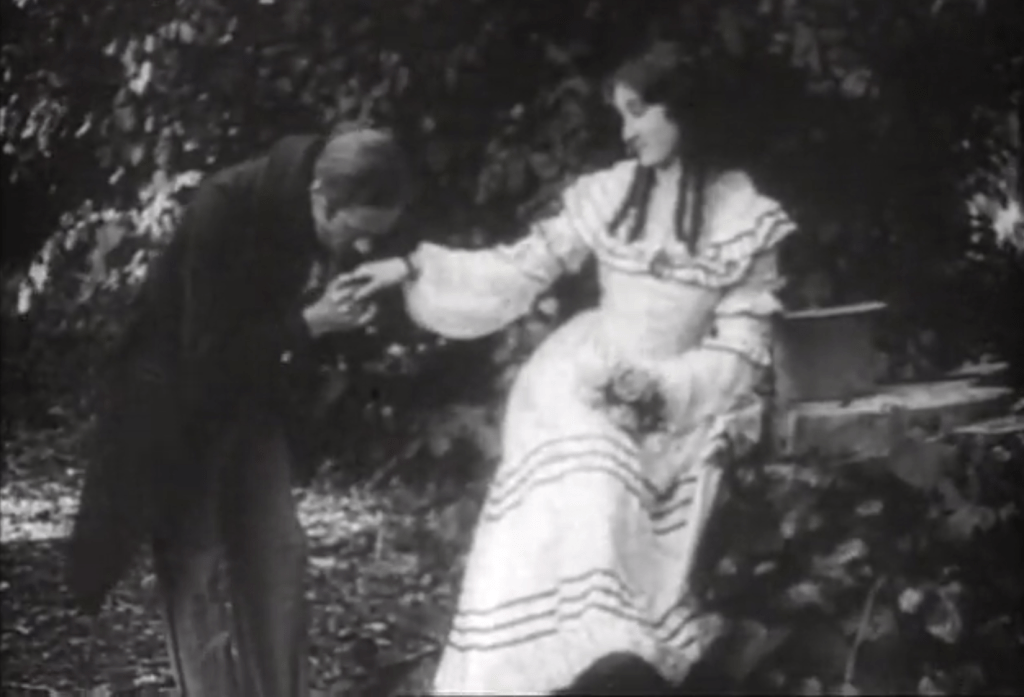

Identifying Silent Film Actors

Uploaded 5 September 2025

Identifying film actors who are not listed in the credits or misidentified can be a tricky business, because available filmographic resources are not always accurate and comparing images can be deceiving. I ran into this problem a number of years ago, when I helped Northeast Historic Film identify an unknown biblical epic that had been distributed in America as The Fall of Jerusalem, but turned out to be Jeramias (1923, Eugen Illés), a German film. IMDB is often not completely reliable because it is a user-generated site that depends on input and corrections from the public. I encountered both filmographic inaccuracy and photo identification issues recently again, but, as in the case of Jeramias, both issues were solved through the concerted effort of a number of international film scholars and collectors, including Jean Ritsema, Ivo Blom, Johan Delbecke, and Werner Mohr.

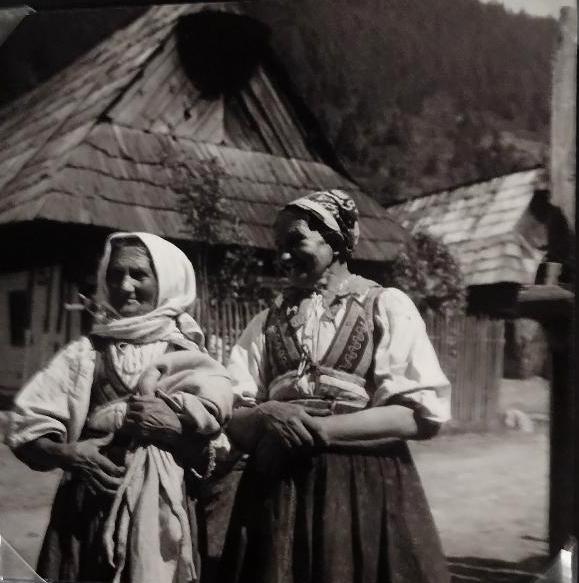

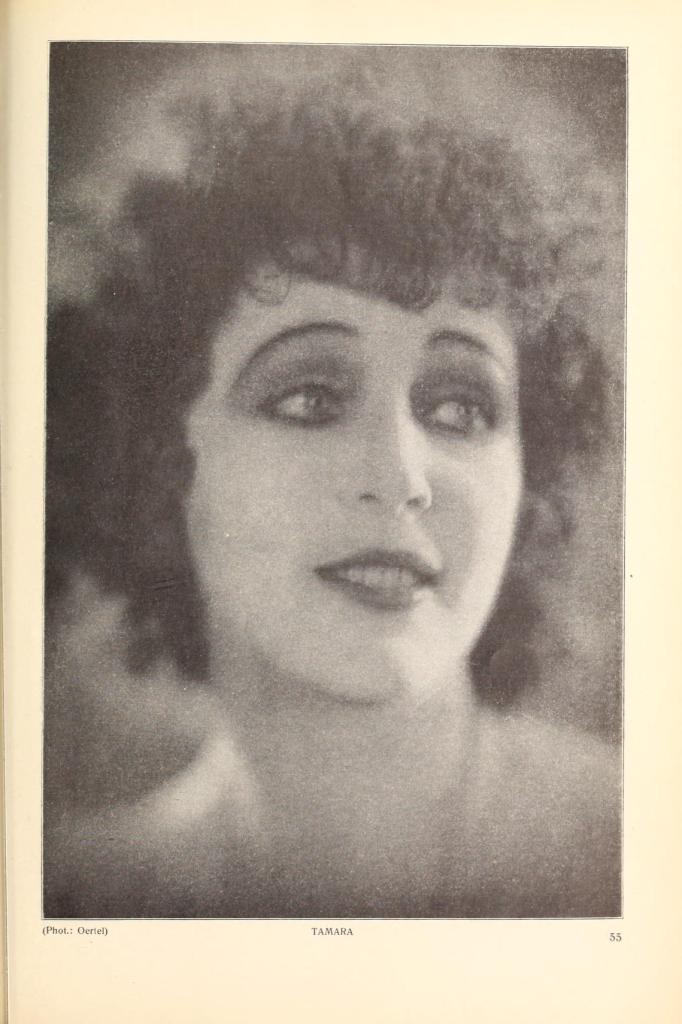

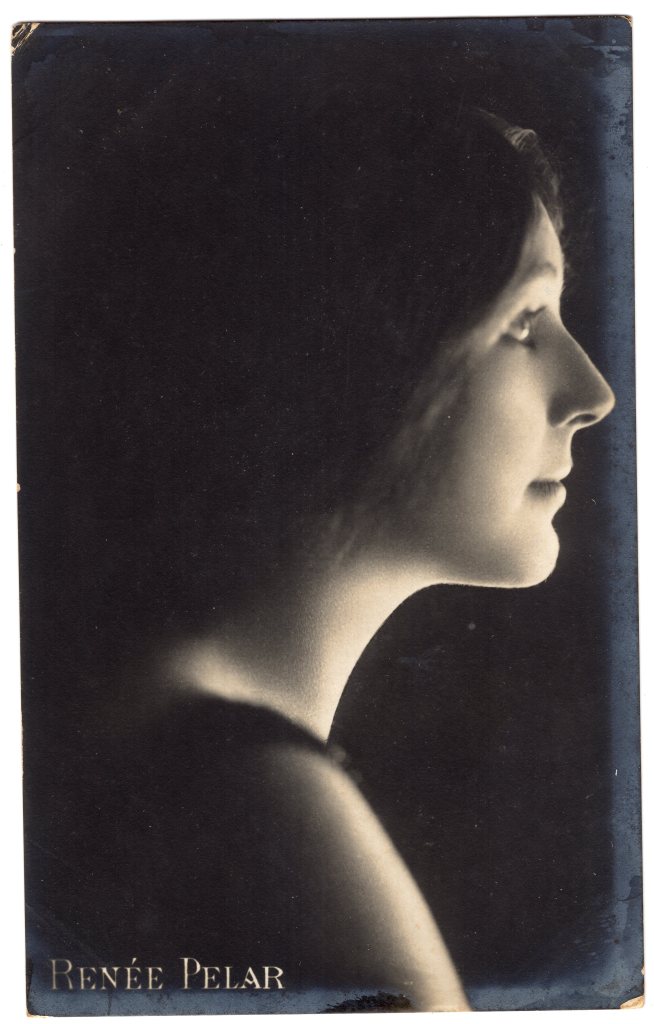

The story begins when Michigan collector Jean Ritsema contacted me in early July about identifying a postcard for “Tamara Karsavina” (Traldi 863, Ross Image Archive) from the German collector Werner Mohr, which they believed might be a shot of the character of Oberon in the German film, A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1925). I had written about that film (https://archivalspaces.com/2023/08/04/327-a-midsummer-nights-dream/) and had misidentified Oberon as Tamara Geva, as had the San Francisco Silent Film Festival and other sources. Ritsema stated that the Russian ballerina was probably still in Russia when the film was made, and also noted that she looked very similar to Tamara Tolstoi in The Joyless Street (1925), which I had restored at the Munich Filmmuseum. She also sent me a 1925 interview with Tamara (no last name) from the German fan magazine Filmland (No. 8, June 1925), which included a photo recognizable as the actress “Tamra Tolstoi,” playing Lia Leid in The Joyless Street. According to the interview, Tamara had started her career with Friedrich Zelnik in a film later identified as Eugen Onegin (1919), where she used the pseudonym Thea Pellard. Next, Ritsema sent me a link from a Belgian postcard collector, Johan Delbecke, to an “Erna Thiele” webpage by Stephanie D’heil (www.steffi-line.de), suggesting that Dorothea Elise Alma Gertrud Thiele, an actress prominent in the mid-1910s in Germany (Homunculus, 1916), may have used various pseudonyms, including Renée Pelar, Thea Pellard, and Tamara. After her retirement from the screen, she married the Swiss painter, Peter Voltz, and became a painter herself, Tamara Voltz. I responded that it was strange that in the Tamara interview, she had not mentioned her earlier German career. The photo of Erna Thiele on the webpage also looked very unlike the dark-haired, “Russian” beauty of Lia Leid.

Over the next weeks, we both attempted to research Tamara Geva and Tamara Tolstoi. Geva, as Ritsema noted, apparently made two films for UFA, but was only in Berlin a couple of months before moving on to Paris with her husband, George Balanchine. None of the films credited on IMDb to Geva were produced by UFA, but Gräffin Plattmamsell (1926) was distributed by UFA. Was this Geva or Tamara, or Thiele? Through continued research, I realized that Countess Tolstoi credited in the Joyless Street was actually the daughter of Leo Tolstoi, and was on a lecture tour through Europe in 1925, but was about 60 years old and played Valeska Gert’s brothel assistant. At the Munich Filmmuseum, we had credited Tamara Tolstoi as Lia Leid, but now I was no longer sure since no German version credits of the film had survived. On the other hand, a contemporary reviewer had eroneously listed Lia Leid as Countess Tolstoi. We also followed up on a lead from Ivo Blom that a Countess Tolstoi had appeared in La Petite Marchand d’Allumettes (1928) as a woman with a dog, again obviously the older Countess.

Ritsema had contacted Blom, a well-known Dutch film historian and specialist in Italian Cinema, to research the Italian films mentioned by Tamara in her interview. Blom consulted Vittorio Martinelli’s Il cinema muto italiano, Vol. 1920 and discovered that Renée Pelar had indeed starred in several Italian films in the early 1920s, including Liberazione (1920) and La donna del mare (1922). So Renée Pelar was another pseudonym for Tamara, but was she also Erna Thiele? The Erna Thiele website had also named a source as documentation for her later marriage to Voltz, so Ritsema looked up the book on WorldCat and found that a copy was housed at the UCLA Library. I ordered the book, Alfred A. Häsler’s Außenseiter-Innenseiter, 28 Porträts aus der Schweiz (1983). A chapter in the book on the Swiss painter, Tamara Voltz, confirmed that she had been born in Berlin on 23 March 1896 and spent much of her life in Locarno, Switzerland; she died in Klosters on 4 August 1985. So we thought Dorothea Thiele was indeed Erna Thiele, but also Thea Pellard, Renée Pelar, and Tamara in her fractured film career.

But in a final twist, Jean Ritsema wrote to me on the day the first version of this blog was published that Erna Thiele and Dorothea Thiele are two different actresses; the former was born in St. Petersburg on 6 May 1895 as Erna Josephine Thiele. Her filmography has now been corrected on IMDb. We still don’t know what Tamara Geva’s only possible German film credit was.