Archival Spaces 260

Restoration of Paul Leni’s Waxworks (1924)

Uploaded 8 January 2021

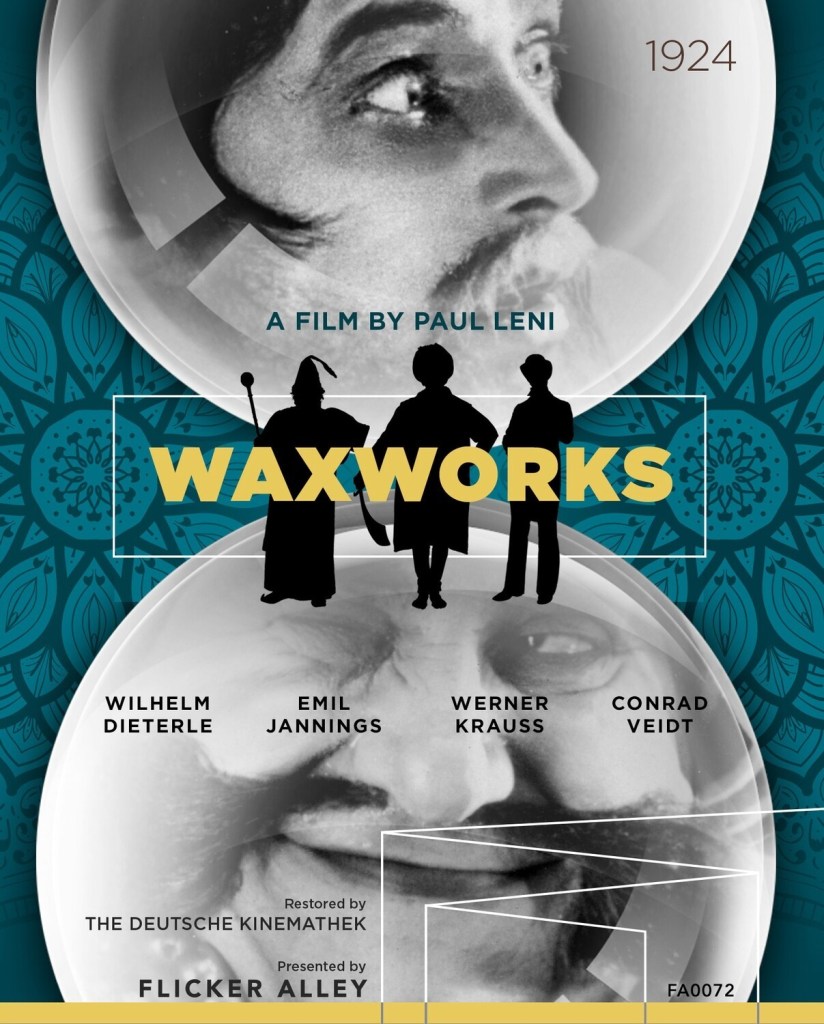

A courageous little distributor of classic and silent films, Flicker Alley has just released a blu-ray-DVD dual-format edition of Paul Leni’s canonical Das Wachsfigurenkabinett / Waxworks (1924), directed by Paul Leni. This new digital restoration, carried out by the Deutsche Kinemathek, Berlin and the Cineteca di Bologna, offers a completely new visual experience. I had previously seen a number of different 35mm prints while researching the German-Jewish photographer/cameraman, Helmar Lerski, but all of them originating from the nitrate master positive at the British Film Institute. Seeing Waxworks in this new digital version revealed many visual details previously hidden in the patina of the emulsion, but digitality has its own pitfalls.

Waxworks is considered by film historians to be a “pure” Expressionist film, like The Cabinet of Caligari and Genuine (1920), all films defined by their expressionist décor, visual design, and acting style, in contradistinction to more realistic Weimar era films, like The Last Laugh (1925) and Metropolis (1927), which have been said to display expressionist lighting and camera angles. Interestingly, Waxworks, as the last pure expressionist film, is also the first to highlight expressionist lighting, as it would be inherited by American film noir, thanks in no small part to Jewish émigrés from Berlin. Not surprisingly, Waxworks opens, like Caligari, on a fairground, a place of wonder in German cinema, as well as the first home of cinema.

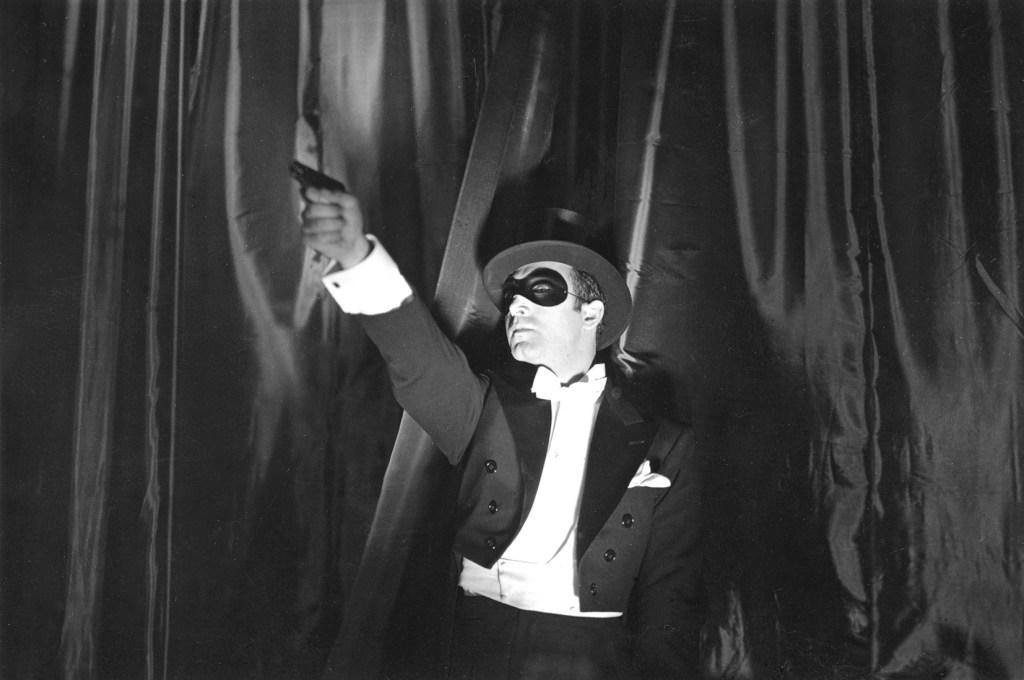

Waxworks relates the stories of three historical figures, depicted in a fairground wax museum, Haroun al Rashied, the Caliph of Bagdad, Ivan the Terrible, and Jack the Ripper. In the film’s frame story the attraction’s owner hires a young journalist to create stories for his wax figures, which in their cinematic incarnation are played by Emil Jannings, Conrad Veidt, and Werner Krauss, respectively, the three most famous actors of the era, while a young William Dieterle impersonates the writer. Interestingly, the three stories are not weighted evenly in terms of length – indeed a fourth episode, Rinaldo Rinaldini was never shot, due to budget issues, although the figure is clearly visible in the attraction’s line-up – nor are the episodes stylistically similar beyond some expressionist features.

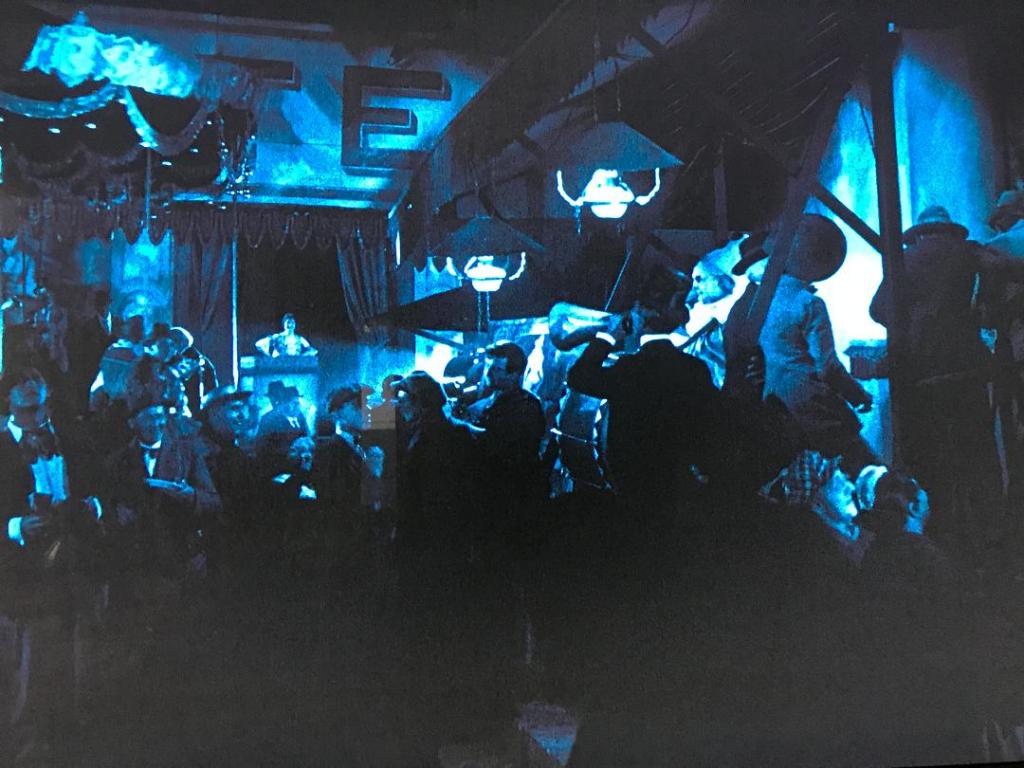

The 1001 Nights sequence is relatively evenly lighted (except later night scenes), in order to highlight the outrageous set design, a riot of intestinal passageways, rotund architecture, oversized balloon-like headdresses, and obese bodies. The shorter Ivan the Terrible story intensifies the gaze on elongated, tortured bodies, their agony inscribed on faces in high-key lighting. The final Jack-the-Ripper sequence turns the journalist narrator into a subject, as he dreams, the serial killer is stalking his sweetheart, the proprietor’s daughter. Only roughly five minutes in length, the sequence is a densely constructed series of superimpositions, in which the hero and heroine are haunted by the phantom image of Jack, the Ripper. Not only are the episodes shorter, but their central characters are progressively less developed with Werner Krauss literally a ghost without a solid body.

According to Jürgen Kasten’s Der expressionistische Film (1990), the Berlin premiere version of 12 November 1924, began with the Ivan episode, then Jack, then Haroun al Rashied, but was changed shortly after. Budget issues and a lawsuit by the screenwriter Henrik Galeen delayed the production which probably began in Summer 1922, and caused the elimination of Rinaldini, with shooting completed in November 1923.

It has long been my contention that Helmar Lerski, the film’s cinematographer has been unjustifiably ignored in favor of Paul Leni’s highly stylized and abstracted sets. While comedy and playful set design dominates the first story, the Ivan and Jack episodes, in particular, allow Lerksi to create filmic space solely with light, through high key close-ups and intensely lighted figures within a black frame. This manipulation of cinematic space through light matched Lerski’s practice of making close-up photographic portraits, for which he often used black velvet, wide-angle lenses, and a battery of Jupiter lamps and mirrors, to eliminate all superfluous visual information, and thus better explore the landscape of the face. The Jack the Ripper sequence’s almost cubist visual design, layering superimposition over superimposition, would not have been possible without Lerski’s framing of bodies against black backdrops.

The new restoration’s carnivalesque tinting and toning seem to emphasize the intense pools of light that structure the images (excepting the Haroun al Rashied episode), but digitality also flattens out space, thus intensifying the effects of Paul Leni’s abstract stage and costume design. Indeed, the tinting turns even scenes with movement from background to foreground into two-dimensional spaces, given the saturation of the tints. The digital image flattens space, obliterating any sense of fore and background, because scanners remove grain and sharpen all data, eliminating depth cues based on focus. But viewing habits are changing, so many may prefer such images.

Apart from the two discs (DVD & Blu-ray), the set includes a handsome booklet, an audio commentary by Adrian Martin, an interview with Julia Wallmüller from the Deutsche Kinemathek about the restoration, a conversation with Kim Newman, as well as a bonus of Paul Leni’s short crossword puzzle films, Rebus-Films Nr. 1 (1926).