Archival Spaces 303

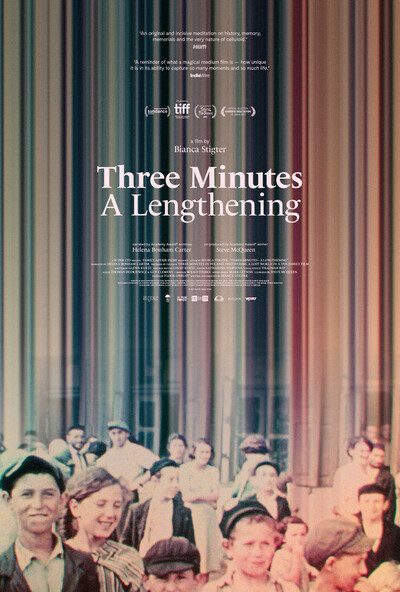

Three Minutes. A Lengthening (2022)

Uploaded 2 September 2022

In the Summer of 1990, after the fall of Communism, I visited Poland for the first time, training docents for a United States Information Agency exhibit on American cinema in Katowice. On a free day, I asked my driver to take me to Auschwitz which was a few hours away. We first went to Auschwitz I, which was the work camp, where both a film and all exhibition signage failed to mention the word Jew, but only the nationalities of those incarcerated and killed there. Afterward, I wanted to see Auschwitz-Birkenau, the death camp, which proved challenging, because there was no signage anywhere to give directions. When I found it, I was surprised to see that the Poles had built housing within 200 ft of the gas chambers. I was reminded of that moment, when in a new film, Three Minutes (2022, Bianca Stigter), the narrator, Helene Bonham-Carter) describes the market square in the town of Nasielsk, Poland, today, a small town where almost half of the pre-World War II population of 7,000 were Jewish, yet not a single sign, marker, or plaque marks their disappearance in December 1939, when virtually every last Jewish inhabitant was deported to Warsaw’s ghetto, before being murdered in Treblinka three years later.

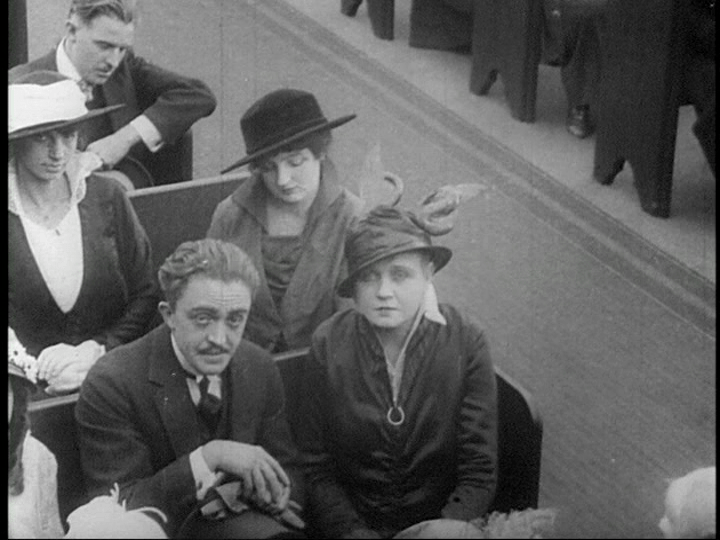

A remarkable new documentary, Three Minutes recently opened in Los Angeles after a preview screening, sponsored by Hilary Helstein’s Los Angeles Jewish Film Festival. The film’s title refers to three minutes of degraded 16mm black and white and color footage, taken in the Summer of 1938 in Nasielsk’s town square by David Kurtz, a native son who had emigrated to America as a child and was now returning with his family and some friends. Kurtz’s longer film, Our Trip to Holland, Belgium, Poland, Switzerland, France, and England, produced with a Cine-Kodak camera, documented their grand European tour. Kurtz’s grandson, Glenn Kurtz, discovered the footage in 2009 in Palm Beach Gardens, Florida, and was immediately intrigued by the three minutes of Jewish people in an unidentified Polish town, but everyone who would have known was dead. Glenn Kurtz donated the footage to the Holocaust Museum in Washington, DC, which had the badly decomposed film – due to vinegar syndrome, – digitally restored at Colorlab in Rockville, MD. He then began the difficult process of trying to identify the town and its inhabitants. How do you identify something when there are no prominent landmarks or other identifying marks, like signage?

Glenn Kurtz assumed it was either the town where his grandmother or grandfather were born, but it was only after finding a photo of a Synagogue door adorned with two Lions of Judah that matched the door in the film that he knew it was Nasielsk, a town about thirty miles north of Warsaw, where his grandfather had been born. Finding survivors who might help identify the individuals in the film proved much more challenging. Two years later, he was contacted by a woman from Detroit who recognized her then 13-year-old father in the film; Maurice Chandler was still alive. Eventually, eleven of the approximately 150 persons seen in the footage were identified, of which only a few survived the Shoah. Chandler could only identify males, like his friend Chaim Talmund, because as an Orthodox Jew he was forbidden to look at girls. The story of their horrific deportation from Nasielsk’s town square that December 1939, the initial imprisonment in the town Shul of 1600 of them, their continual beatings by German troops, and their journey in cattle cars to Warsaw, was documented by a Jewish eyewitness who buried his report in the Warsaw ghetto and by a German Wehrmacht Commandant who made an official report. Another survivor tells the remarkable story of how he rescued his girlfriend from the synagogue by posing as a German officer, after an anti-Nazi German officer lent him his winter coat, both then fleeing to Russian-occupied Poland.

Before seeing the film, I was unclear how those three minutes could be turned into a feature-length documentary, but Kurtz and Stigter succeed. Using the tools of avant-garde filmmaking, the director not only repeatedly shows the three minutes in their entirety, while relating the story of the film, but crops, refocuses, reedits, and digitally manipulates the images so that the film seems at times in danger of falling into the abstract. But it doesn’t because while the film employs structuralist repetition, to stretch time, the way the 1960s avant-garde had, especially Ken Jacobs, it simultaneously focuses over and over again on the faces, their look into the camera, their movement out of the synagogue and into the street. While the ultra-Orthodox would not have wanted to be filmed, the narrator notes, the event still “scrambled social hierarchies,” mixing middle-class and working-class Jews, mostly young people and curious adults. One of the most emotional sequences is when the film digitally isolates in close-up every inhabitant visible in the film, creating a full-screen gallery of portraits of the dead. Holocaust researchers usually have names, not faces, while this film offers countenances as the only traces of their human existence, which Kurtz’s film memorialized. Finally, in questioning why so many had congregated in the film in and outside the synagogue, the film speculates that the famous cantor, Moishe Koussevitzky had performed that day: We hear the Cantor’s melodious voice on the track over an abstract image of b & w film grain, which eventually pulls back to reveal the darkness of the synagogue’s entrance, the diegetic source of the music, but also a metaphor for the film’s pulling life from the shadows.

Having literally seen hundreds of Holocaust documentaries, I can say Three Minutes is both unique and an amazing aesthetic experience because it personalizes the stories of six million.