Archival Spaces 328

Bonn Silent Film Festival

Uploaded 18 August 2023

I first wrote about the Bonn Summer Cinema – International Silent Film Festival two years ago. This week I’ve again been able to view films at the Festival for this 39th iteration from 10 – 20 August 2023. As in the past several years due to the COVID pandemic, the Festival has continued to make films available online for forty-eight hours after the screening, allowing not in Bonn to actually view the program. The show was programmed by Artistic Directors Eva Hielscher and Oliver Hanley. The Festival is continuing for a couple more days, so you still have an opportunity to see films @ https://www.internationale-stummfilmtage.de/en/home-en. What I like about the Bonn Film Fest is that they consistently show unknown or little-seen work, rather than the classics, which ostensibly would bring more audiences. I was able to see a number of films on my bucket list and discovered several more that were completely unknown to me.

Like many Weimar era German films, Groβstadtschmetterling/City Butterfly (1929, Richard Eichberg) opens on a Caligari-like fairground, where the grotesque Coco the Clown (Alexander Granach) doubles as a barker for the show, where Mah (Anna Mae Wong) is an exotic dancer. Coco is in love with Mah, forcing unwanted attention on her, even after she escapes the itinerant life. Her budding relationship with Kusmin, a Parisian painter, is interrupted by a wealthy female patron who becomes Kusmin’s lover. The film thus avoids the specter of miscegenation, leaving the film’s star, Anna May Wong, to relinquish her object of desire. Anna May Wong was a huge star in Germany and the U.K. after Richard Eichberg brought her to Europe in 1928 from Hollywood, where she was only playing Asian stereotyped secondary roles. She starred in four films, including the multiversion Hai-Tang (1930), before returning to B-film Hollywood.

Even though I had researched pioneering woman director, Germaine Dulac who not only helped establish the first French film avant-garde but also published film theoretical work, I had not seen L’invitation au voyage (1927), which was recently restored at Amsterdam’s EYE Museum. The film follows a neglected housewife as she visits an exclusive club for upper-class patrons wanting to consort with sailors. The opening design recalls German expressionism, and Dulac constructs a film and meta-film that remains totally subjective through a visual orchestration of looks, gestures, and objects, while providing a catalog of new film techniques, including accelerated montage, superimpositions, quick pans and tracks, out-of-focus shots, and fast motion. Insisting on the legitimacy of woman’s desire, even in tawdry haunts, Dulac crafts romantic visions of love that allow for a return to the real world.

I had seen the Norman Studios’ all-black cast melodrama, The Flying Ace (1926), but was impressed this time with its very professional editing. Starring Laurence Criner and Kathryn Boyd, the former railroad detective who solves a robbery, the primary suspect being the girl’s father, the film is one of the few all-black cast films from the 1920s that has survived intact. Although the film is deeply rooted in middle-class values, I was struck by the negative image of the local cop, whose mixture of Keystone oafishness and serious danger seems to embody the black community’s ambiguous relationship to the police. The real hero of the film, as far as I’m concerned, is the one-legged assistant to the detective (Steve Reynolds), who disguised as a bum chases down the robbers on foot and with a bicycle, his crutch morphing at one moment into a leg for peddling and into a rifle the next. Unfortunately, the producers had no funding for actual flying sequences – they are staged – unlike L’Autre aile/The Other Wing (1924, Henri Andréani), which has spectacular aerial sequences in its story of two feuding aviatrixes. Unfortunately, much of the film is boudoir drama, staged by a film director who began his career in 1908.

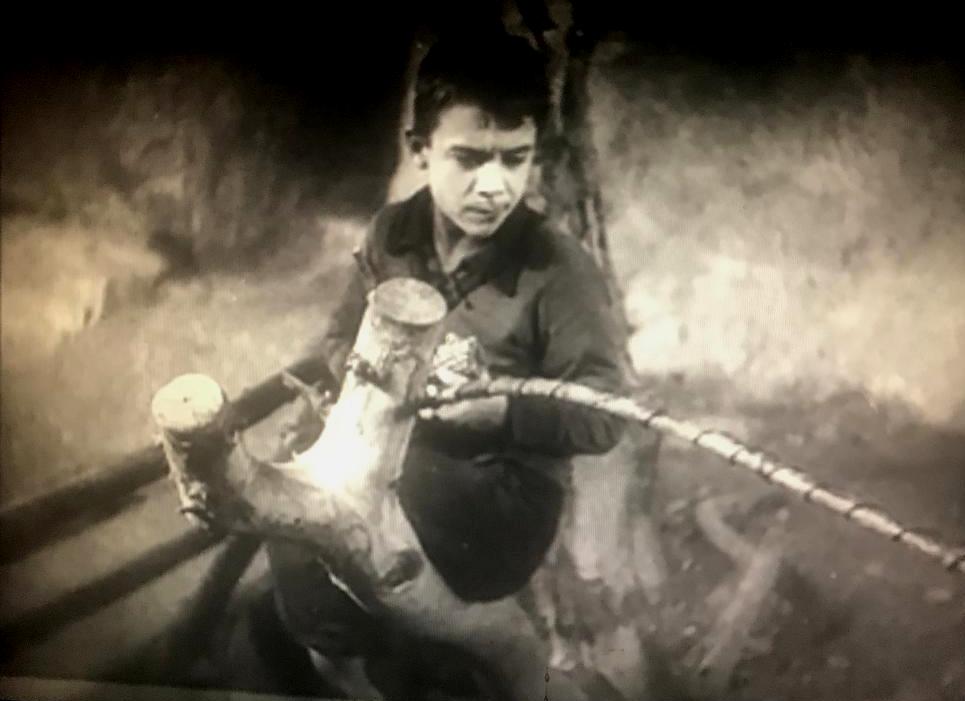

The previously lost Ukrainian silent, Congratulations on Graduating (1932), is the first children’s feature by Ukrainian woman director, Ivha Hryhorovych. It is thanks to the Federal German Archives that this film (and the likewise previously lost Ukrainian Pigs Will Be Pigs [1931]), were digitized from 35mm prints that had been placed in the Nazi Reichsfilmarchiv; both silent films include a title that states it is a punishable offense to reveal the film’s contents to the public. Made after the institutionalization of Stalinist Socialist realism, the film does have its propagandistic elements. But Hryhorovych also inserts a feminine, sympathetic depiction of a bullied teenager who attempts suicide because he is a poor student and will be kicked out of the Young Pioneers. The director’s lyricism also recalls Alexandr Dovzhenko in her love for nature in the Ukrainian countryside and moments of tenderness in the depiction of children on the cusp of adulthood.

Another Ukrainian film that shared Dovzhenko’s love of nature was In Spring (1929), directed by Mikhail Kaufman who was the cameraman in Dziga Vertov’s The Man With the Movie Camera (1929). He was also Vertov’s brother and had a falling out with him which lead Kaufman to produce his own film, even using rejected out-takes from Vertov’s film. In Spring, while featuring similar montage and camera techniques to the earlier film, focuses much more on nature and on individuals, opening with scenes of melting snow, showing people at work and at play, and observing birds in their nests. This version, restored by Amsterdam’s EYE, includes 20 minutes more footage than the YouTube version, specifically footage of Orthodox religious processions which were cut by the Soviet censors. It ends with a joyous montage of peasant dancing, thereby highlighting community rather than technology, as had Vertov’s film.

As noted, six more films will be available online through 23 August. The films are accompanied by internationally known musicians, including the Aljoscha Zimmermann Ensemble, Cellephone (Paul Ritell, Tobias Stutz), Neg Morley, the Monte Alto Motion Picture Orchestra, Elaine Loebenstein, Filmsirup (Michael Hendricks, Christian Carazo-Ziegler), Misha Kalinin/Roksana Smirnova, Richard Siedhoff, Neil Brand/Frank Bockius, Daan van den Hurk/Mykyta Sierov, Stephan Horne, Elizabeth-Jane Baldry, Céline Gailleurd/Oliver Bohler, and Teuvo Puro.