Archival Spaces 360

Ich klage an / I accuse (1941)

Uploaded 15 November 2024

My German-born mother once confessed to me that she was in favor of mercy killing if someone was terminally ill because as a teenager in Cologne, she had seen Ich klage an (1941), Wolfgang Liebeneiner’s propagandistic endorsement of euthanasia, lavishly produced under close supervision of Joseph Goebbels. Having just reviewed Barbara Hales’ excellent new monograph, Transmitted Disease. Eugenics and Film in Weimar and Nazi Germany (Berghahn, 2024) for Medienwissenschaft, I had to think about my mother who told me that story when she was dying of cancer. I had rewatched Ich klage an after finishing the review but I wasn’t going to blog about it, until, by total accident, I viewed Berlin Correspondent (1942, Sidney Lanfield) on YouTube, a film I had not previously seen in my anti_nazi film research. Made less than a year after Ich klage an’s German premiere the American film directly responded to the prior film with an expose on Nazi euthanasia.

Ich klage an pursues two separate narratives. In the first, Hanna, a beautiful, young, and vivacious woman, played by Heidemarie Hatheyer, is married to a famous research Professor of Medicine (Paul Hartmann). She contracts multiple sclerosis, finally asking her husband to poison her before she suffocates in the disease’s final stage. She dies a wonderful, romantic death in the arms of her husband, happy and pain-free. It is implied that both are aetheists, as was the National Socialist state. The Professor is put on trial but is acquitted when his close friend (Mathias Wiemann), a doctor who had turned down Hanna’s request for assisted suicide on moral grounds, has a change of heart about euthanasia. He has been treating little Tude, a baby who contracted meningitis and was now “blind, deaf and idiotic,” their parents wishing a mercy death for her.

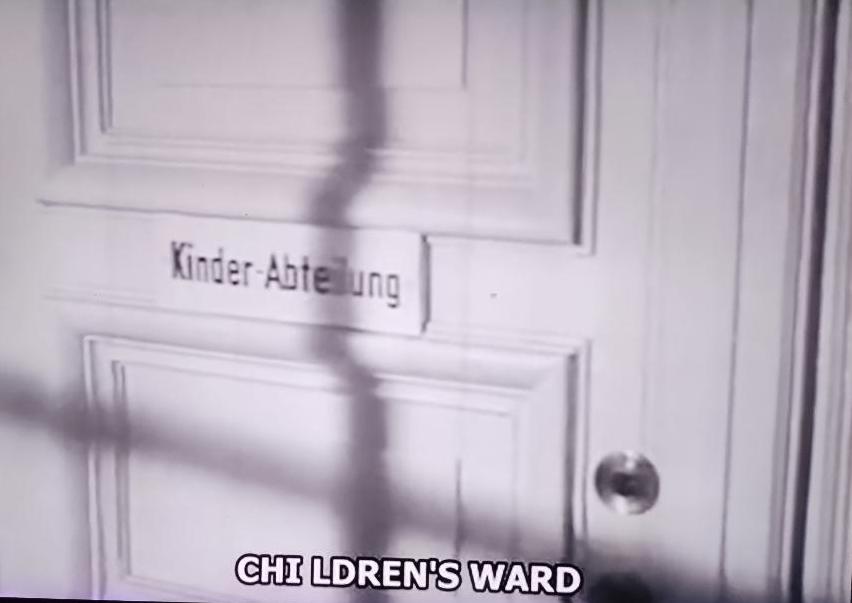

In contrast to the first plot, the second story of the child’s birth, her treatment for the disease, and final vegetative state take only a few minutes of screen time, the stricken baby remaining invisible behind a closed door, her state only verbalized by the doctor as hopeless, a cross intimating her death. Ich klage an thus briefly mentions the possibility of a state-sponsored euthanasia program, but only abstractly, without revealing real human bodies, while allowing the viewer to bathe in the warm glow of a star-studded, romanticized euthanasia, based on personal choice. I’m not surprised my mom fell for the ploy, although she was otherwise anything but a Nazi.

The reality of the Nazi’s T-4 Program, implemented even before Ich klage an opened, was that 70,000 physically or mentally impaired German citizens were gassed, poisoned, or starved to death. Before May 1945, everyday German doctors, working conscientiously in public hospitals and institutions murdered another 130-180,000 helpless victims, doing their “patriotic” duty, for which virtually no one was prosecuted after the war. Only the Catholic Church, especially the pastoral letter and sermon of the Bishop of Münster, later Cardinal Clemens August Graf von Galen, in the fall of 1941, indicated there was passive resistance to the notion of state-sponsored euthanasia.

In my dissertation, I wrote about an anti-Nazi film, Women in Bondage (1943), which alluded to the Nazi euthanasia program. It was a low-budget Monogram film, produced by Herman Millakowsky, directed by Steve Sekely, and written Frank Wisbar, all three German-speaking émigrés. In visualizing the Nazi education of young women to become loyal child-birthing machines, Bondage shows an SS officer in an insane asylum preparing a deadly injection for a rebellious girl, then quotes her grandmother (the great Gisela Werbesirk): “I’m waiting to be led away to my death. Mercy killing they call it…”

The subject was possibly familiar to American readers through the New York Times which reported on Count von Galen’s condemnation (6-8-42) of “unauthorized killings of invalids and the insane,” and at least one non-fiction book had exposed these Nazi policies, Gergor Ziemer’s Education for Death (1941) noted: “The Hitler chamber was a little white hospital, where underprivileged weaklings went to sleep.”(p. 77). Otherwise, Nazi euthanasia remained virtually unreported in the American press during the war years.

Less than a year after the September 1941 release of Ich klage an, 20th Century-Fox released Berlin Correspondent, which specifically addressed Nazi euthanasia. When an American radio reporter (Dana Andrews) sneaks information out of Nazi Germany, his German contact Mr. Hauen is arrested and sent to an insane asylum; his Nazi daughter (Virginia Gilmore) who had denounced him, complains to her Nazi boyfriend (Martin Kosleck): “I’ve heard of the Gründorf Asylum. He’ll be murdered there. People who are sick, crippled or puny, they send them there and they don’t come back.” In a later scene in the Gründorf facility, the head doctor (Sig Ruman) tries to convince a patient (Paul Andor) to sign a release, so they can operate/kill him, when he is interrupted by the reporter, disguised as a high-level Wehrmacht psychiatrist, who inquires about methods of mercy killing. The doctor admits that many inmates are not really insane, but deserve to disappear, like one very young girl in a cell with polio. He also shows him a cell with Hauen, explaining that sometimes politicals are sent to be disposed of.

Thus, while Berlin Correspondent’snarrative is highly improbable, even silly at times, it is worth noting that it is a rare example of a Hollywood anti-Nazi film directly addressing Nazi euthanasia when most mainstream media in America avoided discussion of these Nazi atrocities.