Archival Spaces 364

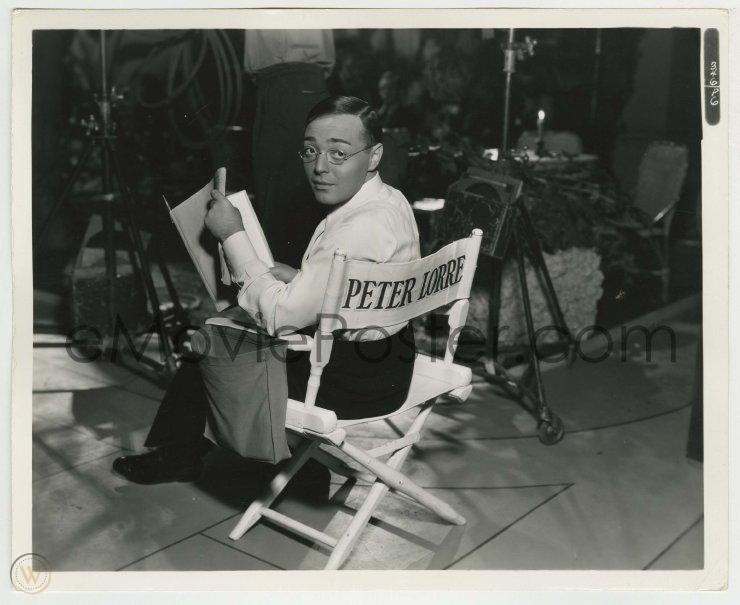

Peter Lorre’s Mr. Moto Detective Series

Uploaded 10 January 2025

When Adolf Hitler ascended to power on 30 January 1933, Peter Lorre knew he would be at the top of Joseph Goebbels’ enemies list, having been the star of Fritz Lang’s M (1931), a film that called for sympathy for a mentally ill mass murderer. While it took the Nazis until July 1934 to ban M, Lorre had left for Paris in March 1933, where he joined fellow penniless, German Jewish refugees, like Billy Wilder, Franz Waxmann, and Friedrich Holländer at the Hotel Ansonia, an establishment that didn’t ask too closely about police permits. While in France, Lorre appeared in two French films by German émigrés, including Du haut en bas (1933, G.W. Pabst), in which Lorre had a cameo as a beggar, reflecting his actual real-life status. Lorre then moved on to London, where Ivor Montegue suggested the actor to Alfred Hitchcock, who cast him as the criminal mastermind in The Man Who Knew Too Much (1935), shot in Spring 1934, before Lorre and his wife, Celia Lovsky embarked in July for America and Hollywood. After starring roles in Mad Love (1935, Karl Freund), Crime and Punishment (1935, Joseph von Sternberg), and Hitchcock’s Secret Agent (1936), Lorre accepted a contract at 20th Century-Fox to star in a new series, featuring the Japanese amateur detective, Mr. Moto.

Mr. Moto had been the subject of a series of extremely popular novels by John P. Marquand, serialized in the Saturday Evening Post, beginning with No Hero (1935), which the writer consciously created as a successor to the Charlie Chan novels, whose creator Earl Derr Biggers had died in April 1933. Given that Japanese aggression in Manchuria (1931) and Shanghai (1932) was well-known, it is surprising that Marquand and Fox would choose a Japanese hero for their detective series, but then most Americans only slowly perceived a Japanese threat across the Pacific. It was however the third Marquand novel, Think Fast, Mr. Moto (1937, Norman Foster) that became the basis for the first film adaptation, starring Peter Lorre.

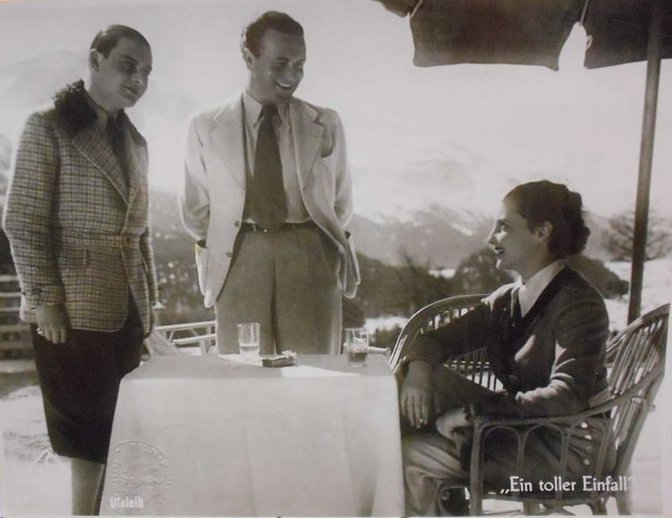

In contrast to today’s prohibitions against “yellow face,” no one in Hollywood seems to have been bothered by an Austrian Jew playing an Asian detective, – except probably Asian actors – or the fact that his Japanese character sounded more like a German. Eschewing prosthetics, Lorre slipped convincingly into the role with a bit of eye make-up, round glasses, and black-dyed hair. Ever polite and speaking in soft measured tones, one can imagine that Lorre was initially drawn to the character because he was both a positive, intelligent figure and an action hero who could use judo to neutralize foes – a double handled the judo – unlike the typecast monsters and villains he had been playing. The film was a major box office hit, leading to the production of seven more Mr. Moto films until Lorre bowed out in 1939.

As Lorre soon realized, the Mr. Moto programmers, running barely more than an hour, were extremely formulaic, even silly, souring him on the character, even if Lorre could have fun slipping into numerous disguises. But within the narratives, the disguises also reveal Mr. Moto as a morally ambiguous character who the Caucasian hero and heroine often have trouble reading. Through the first half of Think Fast, Mr. Moto (1937, Norman Foster) it is unclear where Moto’s sympathies lie, with the smugglers or the police. His face is often a tabula rasa, even with friends, thus conforming to “the mysterious Oriental” racist stereotype. White supremacy demanded vigilance, especially in Hollywood. In Thank You, Mr. Moto (1938, Norman Foster), the second in the series, there is likewise, a hint of moral ambiguity, given how Moto covers up his killing of one person, then kills several others. The white hero and heroine wonder repeatedly, whether they can trust the non-white Moto.

Situated in exotic locales in Asian jungles, the deserts of North Africa and Iraq, or Chinese cities/Chinatown, Moto appearing in the stories as a mild-mannered art dealer or archeologist, covertly tracking criminals, the leaders of whom are often revealed to be upper class and close friends of the male and female hero, who Moto is protecting. In Mysterious Mr. Moto (1938, Norman Foster), the action moves from the swamps of Devil’s Island to the streets of East London, an urban jungle of Cockneys where people of color like Moto are openly subjected to racist slurs. Mr. Moto’s Gamble (1938, James Tinling) features more comedy with Moto playing a professor of criminology, one of whose students is a kleptomaniac who nevertheless helps solve the case.

Ultimately, the Mr. Moto film series are fast-paced good fun within their low budget and wildly incongruous plots. Lorre would, of course, soon move to Warner Brothers, where he became a featured character actor in off-beat roles, like Joel Cairo in The Maltese Falcon (1941, John Huston) and Ugarte in Casablanca (1943, Mi8chael Curtiz). Lorre would return to Germany only once after World War II, directing and starring in The Lost One (1951), a film about a Nazi mass murderer hiding out in a displaced persons camp; the film flopped miserably because no one in Germany wanted to be reminded of their culpability for the Holocaust.