Archival Spaces 367

The First Mexican Sound Film Restored

Uploaded 21 February 2025

Considered Mexico’s first “national” production in the sound film era, Santa (1932) was based on the eponymous Mexican novel (1903) by Federico Gamboa, which is as much a modernist portrait of Mexico City, as it is of the fate of its heroine. Santa, a beautiful country girl, is seduced and abandoned by an Army officer. She goes to the city, where she becomes a well-known courtesan of the wealthy, before descending into poverty and death. The film was featured in “Recuerdos de un cine en español: Latin American Cinema in Los Angeles, 1930-1960,” a major retrospective I co-curated in 2017 at UCLA, however, we were only able to show an unrestored print from Mexico’s UNAM. In Hollywood Goes Latin. Spanish-Language Filmmaking in Los Angeles, I also discussed the importance of Santa’s Los Angeles premiere in establishing a major beachhead for the Mexican sound film industry in America: throughout the 1930s and 1940s, virtually every Mexican film screened in L.A.’s first-run cinemas. Now, Viviana García Besné, the force behind Permanencia Voluntaria, has nearly completed a new restoration, which vastly improves the soundtrack and adds footage previously unseen in any surviving prints. Viviana’s great uncles, Rafael and José and Rafael Calderón (Azteca Films) financed Santa.

On May 20, 1932, the Teatro California in Los Angeles premiered Santa, directed by Antonio Moreno and starring Lupita Tovar, both of whom had substantial careers in Hollywood. According to L.A.’s Spanish language daily newspaper, La Opinión, Santa was coproduced by the Calderóns, who financed the premiere, and which drew an A-list of Hollywood personalities, including Tovar, José Mojica, Mona Maris, Laurel and Hardy, Ramón Pereda, Juan Torena, and Carlos Villarías. Critics praised the film for its realism and its melodrama; it was enormously successful with audiences in the U.S., with theatrical runs held over in many cities.

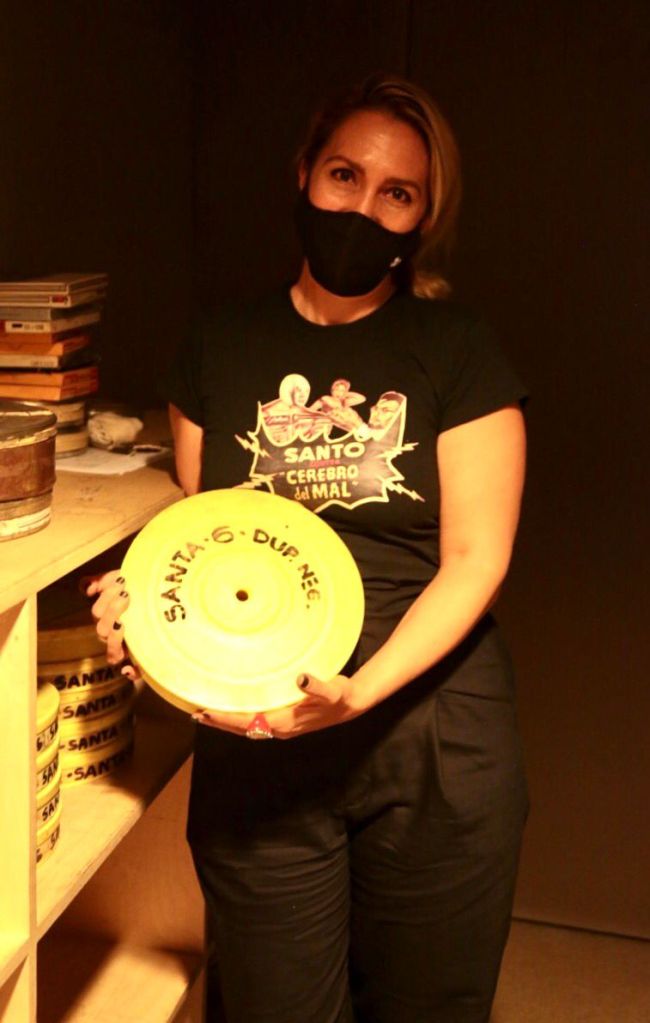

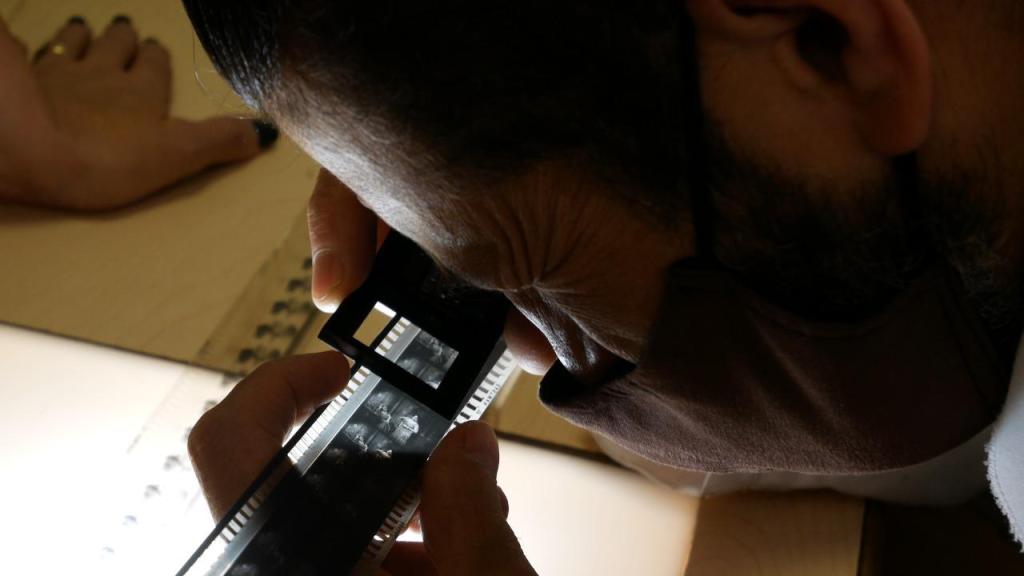

After a worldwide search, Permanencia Voluntaria ascertained definitively that no original negative or master positive of Santa survived, while circulating prints evidenced poor image quality and missing sound. The original negatives for Santa likely burned in the 1982 fire at the Cineteca Nacional’s Churubusco Studios storage. The Cineteca Nacional in Mexico City, however, owned a 10 reel, 35mm, acetate, composite negative (4th generation internegative), with a variable density soundtrack, but image quality was marred by high contrast. Not until Viviana García Besné uncovered six unaccounted-for nitrate reels at the Filmoteca de la UNAM, one including a censored sequence missing from circulating prints, did a restoration seem feasible. Furthermore, Viviana’s team had already found the original Vitaphone 78 RPM sound disks (1932), donated by Paul Kohner (Lupita’s husband) to the Academy Film Archive, an audio source far superior in quality to any of the existing film elements, also running several minutes longer than previous releases. These were lovingly transferred by John Polito at Audio Mechanics.

A VHS release from the 1980s also included some footage not found elsewhere. But where was the missing footage? After months and months of research, it was determined the material had come from a 16mm print at UNAM which had been destroyed years ago. Then, a 16mm print donated by Lupita Tovar, the film’s star, to UCLA proved to be virtually complete, with only a few seconds missing. Miraculously, Tovar’s personal print included a filmed introduction by Federico Gamboa, which had been excised from every circulating version.

Once a new version had been digitally assembled, the team began the complicated task of clean-up and image improvement. Given the severe physical damage, compromised by lossy splices, water damage, projection wear, and poor lab work, extensive hand painting was undertaken to minimize image distortion, followed by dust-busting and stabilization. Next, image grading was done to ameliorate the disparate quality of the source materials, compounded by decades of wear and generational loss. Achieving this, required countless hours of grading and testing, the color correction handled by Ross Lipman, and the digital restoration by Peter Conheim. Finally, the film-out process—transferring the restored digital image back onto 35mm film stock–initially fell short of expectations, because labs today seldom work with b & w materials, but after much experimentation at FOTOKEM the delicate tonal range achieved during digital grading was also visible in output 35mm prints. According to Viviana García Besné, “While a few seconds of Federico Gamboa’s spoken introduction remain missing, this restored version represents the most comprehensive and faithful iteration of the film available today.”

The budget for the restoration of Santa surpassed $100,000. With a matching grant from the National Film Preservation Foundation, Permanencia Voluntaria, has finished most of the work, but still needs $20,000 in completion funds, before the film can be made available for DVD release. Anyone wishing to make a donation to help complete the project can do so at https://pdnfoundation.org/give-to-a-fund/permanencia-voluntaria-film-fund.