Archival Spaces 243

Hugo Haas’ The White Sickness (1937) restored; a Plague Allegory

Uploaded 22 May 2020

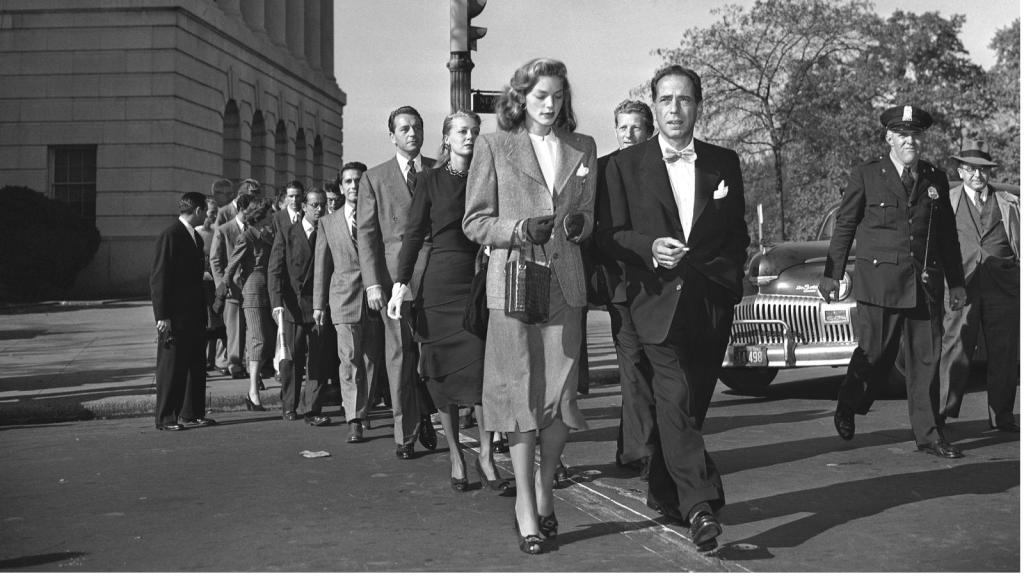

Thanks to my archivist colleague and friend, Adrian Wood, I learned that the Národní filmový archive in Prague has restored Bílá nemoc (1937) from the original nitrate negative (the sound came from a nitrate print) and made it available online on their You-Tube channel with English subtitles (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HJMUIBEzYnI). An adaptation of a play by Karel Čapek, The White Sickness or Skeleton on Horseback, as it was called in the United States, was one of the few films my dad consistently mentioned to me when we talked about films that he remembered from his youth. I was also interested in the film, because it was directed by Hugo Haas, who fled Czechoslovakia after the Nazi occupation in 1939 – he was Jewish – and had an interesting career in Hollywood as an actor and low-budget filmmaker, one of many Central European refugees. Finally seeing the film, I realized that it visualized a worldwide pandemic as a political allegory.

The film opens with a superimposition of soldiers marching towards the camera and a camera moving into a balcony where “the Marshall” gives a bellicose speech, while a large crowd cheers below; he declares the nation ready to enlarge the country’s borders by force. The camera then pans down over the crowd, where we see a bearded gentleman, who we learn later is Dr. Galen, turning away. In the following scene, the camera tracks horizontally from a crucifix to medical charts hanging above bedposts, as patients below muse off camera about their illness which first appears as a form of leprosy with white dermatological spots, but inevitably leads to death. Hugo Haas thus sets up through contrasting camera movement two harbingers of death: 1.) An unnamed fascist regime that glorifies war rather than peace, consciously symbolizing Adolf Hitler and Nazi Germany; 2) A highly communicable, mysterious, and deadly disease, for which there is no apparent cure and which originates in China and is expanding to a worldwide pandemic through hand-shaking. Fascism sacrifices the youth of humanity, the virus kills the elderly who are usually responsible for making wars, i.e. war is like the virus. Indeed, we never see the concrete manifestations of the disease, just as the war itself remains hidden off-screen, amplifying the allegorical nature of the narrative.

Dr. Galen (Hugo Haas), who we see in the first scene, has found a cure, but he is not ready to make it public unless the Marshall and other world leaders agree to forsake their armies and all wars. Instead, he only treats the poor who are unable to pay and are most often the victims of war. The ensuing conflict rages between the forces of the military-industrial complex which are unwilling to give up war profits for peace, and the doctor who steadfastly refuses to treat the representatives of power, as they successively succumb to the white disease. It is only when the country’s megalomaniac dictator becomes ill after he has attacked a small neighboring country (clearly Czechoslovakia) with disastrous effects for his army, that there seems to be hope to end the plague. However, the masses crazed by mindless nationalism have other ideas

Born in 1890 in what is now the Czech Republic, Karel Čapek achieved world renown with his expressionist play, “R.U.R.” (1920), which coined the term robot, and his satirical dystopian science fiction novel, War with the Newts (1936). In 1937, his anti-Nazi play, “Bilá nemoc,” premiered at the Czech National Theatre in Prague, starring Hugo Haas, who also directed. Haas then wrote the screenplay and hired virtually the whole cast of the original for his filmed adaption, which premiered on 12 December 1937. The film was partially funded by the Czechoslovak government, certainly a courageous move at the time. While the film was banned in Nazi Germany, it was released in other European countries before World War II began in Europe. While Čapek died in December 1938, just before the Germans invaded Czechoslovakia in March 1939, – the Gestapo tried to arrest him only to learn he was already dead – Haas supposedly smuggled a print into the United States when he emigrated; it was released by Carl Laemmle in 1940.

Given its theatrical origins, Bilá nemoc is heavily dialogue driven, but is striking for both its leftist political stance – the capitalist armaments manufacturer Baron Krog (Vaclav Vydra) is clearly identified as a willing supporter of the militarist dictator (Zdenek Štepanek), who believes himself to be the savior of the nation and immune to any disease. He recklessly and knowingly shakes hands with the stricken Baron Krug. Thus, the rich and powerful fall prey to their own machinations, while the film saves its sympathies for the urban poor. However, the film ends on a highly cynical note when the masses protest the Marshall’s call for an end to the war. However, for today’s audiences, the film’s depiction of the pandemic, the overriding sense of fear it engenders in the not yet afflicted, the helpless victimization of the innocent, and the incredible arrogance of a leader who believes he is immune with an “I don’t need to wear a mask” attitude, all strike a very contemporary chord for anyone living in coronavirus America.

An incredibly popular star in Czech cinema in the 1930s, Hugo Haas would play mostly supporting roles in Hollywood during the 1940s, but in 1951 saved enough money to set up his own independent film production company, where he began producing, directing and starring in a series of lurid, low budget melodramas. Most are variations on the theme of older men who form liaisons with much younger, often amoral women, including Pickup (1951), The Girl on the Bridge (1951), Strange Fascination (1952), The Other Woman (1953), and Hit and Run (1957).In 1961 he returned to Europe, settling in Vienna, where he occasionally appeared on Austrian television; he died there in December 1968. The White Sickness remains his most enduring work, one of the only anti-Nazi films made in Europe before the Holocaust

For my dad as a seventeen-year-old high school student in Prague,Bila nemoc probably represented a political awakening; less than two years after the film’s premiere, he was incarcerated in KZ Sachsenhausen-Oranienburg and would eventually be active both in the anti-Nazi and the anti-Communist underground.