Archival Spaces 256

Hannah Arendt – the Movie (2012)

Downloaded 20 November 2020

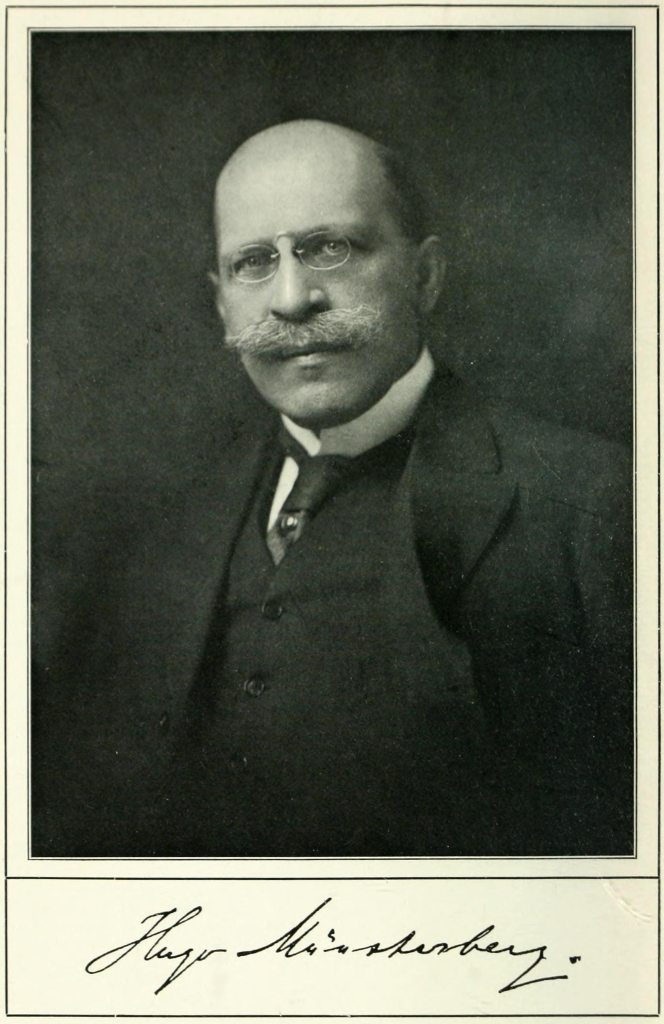

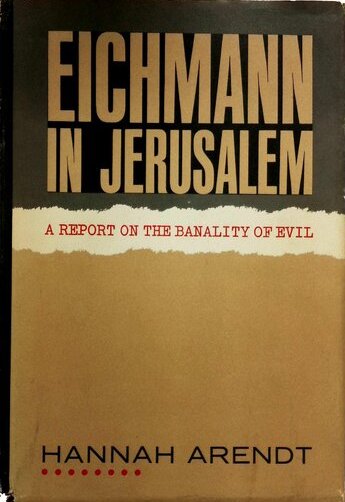

There is a scene near the end of Margarete von Trotta’s masterful biopic, Hannah Arendt (2012), in which Prof. Arendt’s academic colleagues move away from her as she sits down in the faculty cafeteria, after in February 1962 she has published her controversial reportage, Eichmann in Jerusalem. The scene is fictional but is a visual indication of just how Arendt herself became a pariah after the controversy around her New Yorker articles erupted, leading to what Irving Howe in 2013 called a “civil war” among New York intellectuals. Watching the scene, I immediately flashed back to Hugo Münsterberg, one of the first film theorists, who like Arendt was ostracized by his academic colleagues (Harvard), because of his unpopular pro-German views during World War I. Like Münsterberg, Arendt enjoyed popular fame far beyond academia, becoming mass-media stars, publishing bestsellers. Most importantly, both were naturalized Americans of Prussian-German Jewish heritage, who carried with them the intellectual baggage of their upbringing, melding the logophilia of Judaism with the Prussian instance on the letter of the law, principles, and duty.

Rather than present a biography of Hannah Arendt, von Trotta focuses on the period 1961-63, when Arendt traveled to Jerusalem to observe the Eichmann trial. Left out, are her childhood in Königsberg, East Prussia, studies in the late 1920s at university with Martin Heidegger (with whom she has a love affair), Edmund Husserl, and Karl Jaspers, her internment in the notorious Gurs French concentration camp (1940), her emigration to New York, and 30-year marriage to Heinrich Blücher.

The film opens with Eichmann’s dramatic abduction from Argentina by the Mossad, then cuts to Hannah Arendt lying on a couch in her darkened New York apartment on the Upper West Side, smoking; the scene is repeated several times, also ending the film. In this juxtaposition, we get action and thought. Arendt believed in human thought, rejecting Heidegger’s insistence (in a flashback lecture) that thought does not lead to knowledge. Her central concern in the reportage is Eichmann’s ability to act without thought. The closing scene also implies a more emotional level, as Arendt contemplates with a heavy heart the many friends she has lost.

As one friend after another has peeled off in the wake of her Eichmann work, she is unable to compromise her principles, once she formulates her working thesis about Eichmann, even as the film is structured to justify her actions and writing. Two of the most painful scenes of Arendt’s loss involve Kurt Blumenthal (who turns away from her on his death bed) and Hans Jonas, German-Jewish colleagues she had known for more than thirty years.

Actress Barbara Sukowa, who is remembered for her great role in R.W. Fassbinder’s Lola (1981) plays Arendt brilliantly, having previously given a Cannes-awarded performance in Margarete von Trotta’s Rosa Luxembourg (1986), about the doomed leader of the German Communist Party. Although Sukowa in no way physically resembles Arendt, she quietly reproduces Arendt’s intellectual rigor, her stringency, her uncompromising theoretical principles, even in the face of overwhelming public criticism. She is characterized at two different times as arrogant and unfeeling, a view that overlaps with the American view of Münsterberg and his Teutonic pedagogical dogmatism.

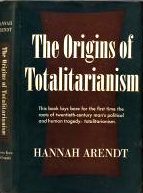

Arendt’s great accomplishment was that she secularized the public discourse around Nazi war criminals, which was still dominated by mythological terms, like, monsters (Hitler), devils (Goebbels), insane demons (Himmler), who had misled the German people, introducing instead the today widely accepted concept of the “banality of evil,” namely that Eichmann was an ordinary, even unremarkable German, a loyal bureaucrat who was only following orders and intentionally turned off his moral compass. Since the publication of Daniel Goldhagen’s Hitler’s Willing Executioners: Ordinary Germans and the Holocaust (1996), we, of course, know that tens of thousands of Germans participated in the murder of the Jews.

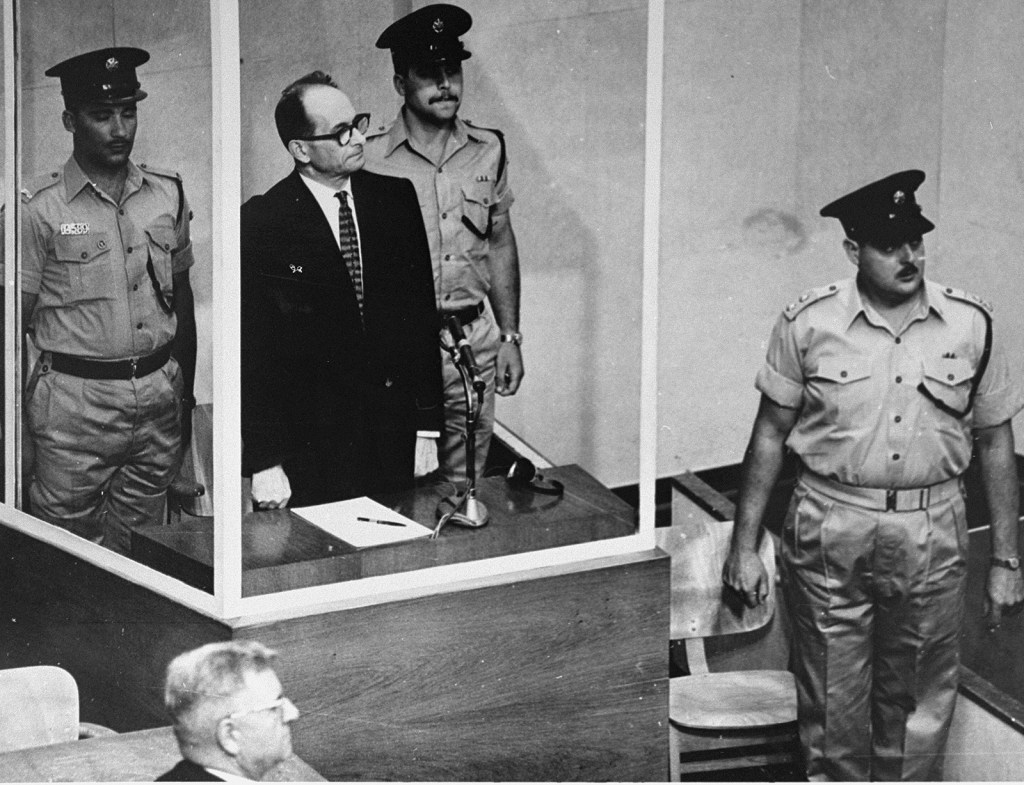

Von Trotta’s film structures the scenes of the Eichmann trial, consisting both of original newsreel footage and staged scenes, to support Arendt’s thesis, showing Eichmann as cold-bloodedly refusing to take any responsibility for the fate of the humans he put on trains to the extermination camps. As Arendt notes in a lecture to her students, neither German Fascism, nor the system of anti-Semitism was on trial in Jerusalem, rather, Eichmann was being tried for his own actions, which could not be directly connected to crimes of murder. Unlike her anarchist-leaning husband, Blücher, who believed there was no legal basis for the trial, Arendt did want to make Eichmann responsible for his actions, supporting his execution. But at the time, few people accepted the premise of “the banality of evil.” Almost half the film, therefore, visualizes the extremely negative public reaction to Arendt’s article by friends, colleagues, and neighbors: A Mossad agent she knew as a student in Berlin threatens her, an upstairs neighbor calls her a Nazi whore in a note passed on by the building’s doorman.

The bone of contention, as even the New Yorker editors recognized before publication, was that many believed Arendt was blaming Jewish leaders for cooperating with Eichmann and, therefore, to blame for their own destruction. In fact, Arendt argued that it was the very amorality of the Nazis, their unwillingness to think about their personal responsibility, rather than rampant anti-Semitism, which allowed for the total moral collapse of both the Nazis and their victims. According to Arendt, the leaders of the so-called Judenrate (Jewish councils) of necessity shared in the responsibility for keeping the trains running. Such a brutal but realistic theory was intolerable to living victims of the Holocaust, less than twenty years after the war. Indeed, Arendt could be criticized for failing to consider their emotional state as survivors. Many scholars also agree that she probably underestimated the virulent emotional and intellectual force of anti-Semitism. Kurt Blumenthal admonishes her for not “loving her people,” but she responds she never loved any people, Jewish or otherwise, but only friends. Ironically, it is those she is losing.

Hannah Arendt believed her own intellectual integrity had to be maintained at all costs, even if she was ostracized, even if uncomfortable truths hurt those around her. Like the Sukowa version of Rosa Luxembourg as imagined by von Trotta, Arendt here is seemingly willing to give up everything for her principles, and her right as a woman to express them; feminist icons in the making. Fulfilling another feminist ideal, Arendt is also portrayed as a warm and loving spouse to Blücher, who had rescued her from Gurs. It was possibly arrogance and philosophical coldness in a man’s world of cuddly women that allowed her to become one of the greatest philosophers of the 20th century.