Archival Spaces 264

Restored Avant-Garde Films from the Netherlands

Uploaded 5 March 2021

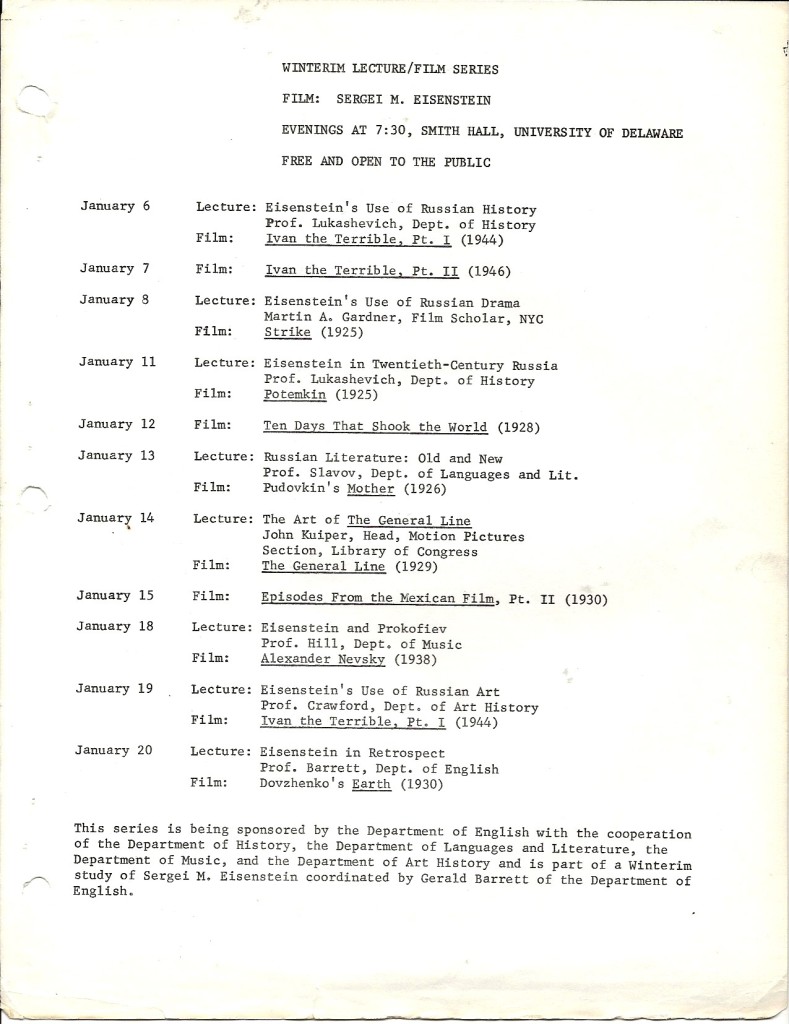

Between February 24 and March 9, 2021, the Eye Museum, Amsterdam and Anthology Film Archives, New York, are presenting a streamed film program, “THERE ARE NO RULES!: RESTORED AND REVISITED AVANT-GARDE FILMS FROM THE NETHERLANDS,” co-curated by Simona Monizza, Mark-Paul Meyer and Marius Hrdy. Originally scheduled as a theatrical series for April 2020 on the history of Dutch avant-garde film from the 1920s to the present – canceled due to COVID), – the present online program focuses on three areas: pre-World War II avant-garde films, screened by the Dutch Filmliga, Dutch avant-garde work from the 1950s, and films by the contemporary filmmaker, Henri Plaat. These five, rare programs, each running about an hour, can be viewed for a nominal. http://anthologyfilmarchives.org/film_screenings/series/53327.

Given my own long-standing interest in the 1920s European avant-garde, I viewed the first two programs, dedicated to works screened at the Dutch Filmliga (1927-1933). My own research in this area goes back to 1979 when I co-curated (with Ute Eskildsen) the 50th anniversary reconstruction of “Film and Foto,” an exhibition of European avant-garde film and photography, curated by Hans Richter and Laszlo Moholy-Nagy. Our show, “Film und Foto der 20er Jahre,” opened in Stuttgart, then travelled to Essen, Hamburg, Zurich, and Berlin, before Van Deren Coke remade the exhibition at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. My essay in the accompanying German catalog (translated into English for Afterimage in 1980), was the first film history to recontextualize European avant-garde filmmaking as a cultural phenomenon, consisting of production, distribution, exhibition, and reception, and not just as a valorization of isolated film artists. It was a methodology I subsequently applied to defining the first American film avant-garde in Lovers of Cinema: The First American Film Avant-Garde (Madison, 1995).

The present Filmliga program is divided into “Shapes” and “Structures,” although the reason for this breakdown is unclear, given that Jan C. Mol’s microscopic films bookend the two programs. Generally, the first program is about humans in relationship with nature, the second about city life. Founded in 1927 by Dutch intellectuals, the Dutch Filmliga was one of many film societies, like the Le Club des Amis du Septième Art in Paris, the London Film Society, and the German Gesellschaft Neuer Film, which hoped to support independent and avant-garde film in the face of American commercial cinema. As a result, the program includes not just Dutch films, but also German, French, and Belgian examples.

Program 1 opens with Jan C. Mol’s From the Realm of Crystals (1927), which uses microscopic and time-altered photography to visualize the growth of various chemical crystals, including boric acid, potassium sulfate, and silver nitrate. Mol’s scientific film was championed by the avant-garde because it revealed the abstract beauty of structures in nature, which were invisible to the human eye but made visible through film technology. Mol’s Crystals and its color remake, Crystals in Color (1927), look surprisingly like abstract modernist art in motion. Henri Chomette had already included similar shots of crystals in his Cinq minute de cinema pur (1925), and, indeed, the trope of abstract art in nature was also mined by Jean Painlevé in France, and photographers Karl Blossfeldt, Albert Renger-Patzsch, and Imogen Cunningham, among others.

The next two films by Belgian film documentarian Henri Storck were shot on the beach at Ostend. Images of Ostend (1929) is a visual poem of sea and surf in the dead of Winter, searching for the abstract beauty of moving water, sand and wind, punctuated by signs of human activity: an anchor, a jetty, an abandoned fishing boat, rapidly edited to convey the rhythm of the sea. Daytrippers (1929), on the other hand, documents with a great deal of humor crowds of beachgoers from all social classes and of all ages congregating, playing, strolling, swimming, lying, and reading in the Summer sun; some wear bathing suits, others wade in their street clothes. Unfortunately, the first-named film is slightly over-exposed, leading to a loss of detail.

French filmmaker Germaine Dulac’s Disc 957 (1929) and German avant-gardist Walter Ruttmann’s In the Night (1931) are very short films (5” & 6”), one silent, one sound, that attempt to visualize music. In both cases, the emotional power of music is equated with lyrical images of nature. Dulac intercuts images of the forest and natural landscapes with animated images of sound waves, a revolving 78 RPM disc, piano hands, and a metronome, all to accompany an absent Chopin Prelude, which was probably played live, but is missing from this performance. Similarly, Ruttmann’s sound film intercuts images of a female concert pianist playing a classical piece with night time shots of lakes seen between the trees, running water, and the surf smashing against rocks.

Sandwiched between these two films is Joris Ivens and Manus Franken’s silent, poetic city film, Rain (1929). Film portraits of cities, beginning with Paul Strand’s Manhatta (1921) and Alberto Cavalcanti’s Rien que les heures (1926) were an almost universal phenomenon in the pre-war avant-garde, as documented the recent publication, The City Symphony Phenomenon (New York, 2019). Shot in Amsterdam before, during, and after a rain storm, Ivens’ camera searches out abstract visual designs in the concentric circles of water falling into canals, in a crowd of umbrellas, in the rack focus of raindrops on windowpanes, in ever-changing cloud formations. As Eva Hielscher notes in the above publication, the rain creates reflective surfaces that act as screens, “generating a new and modern mediated vision, not unlike cinematic perception.”(p. 253)

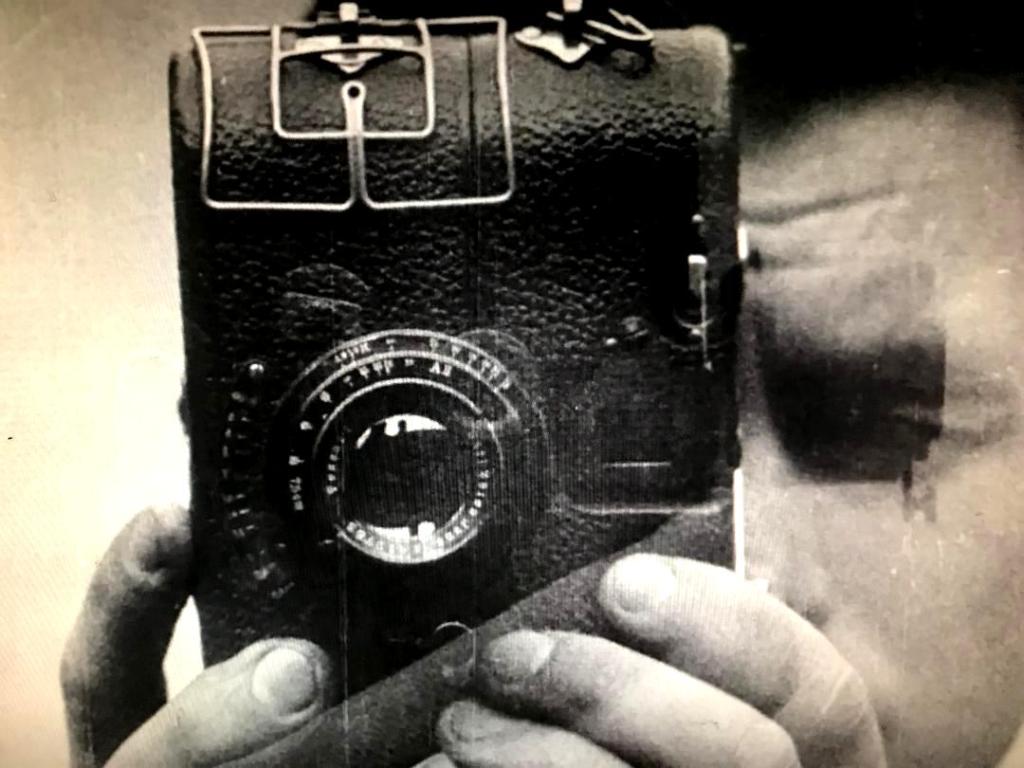

The second Filmliga program continues the theme of city symphonies with Joris Ivens’ The Bridge (1928), a poetic view of a movable, steel-constructed railroad bridge in Rotterdam as it is raised and lowered to allow for river traffic below. De Brug is in fact a visual symphony of moving machine parts, rhythmically cut on movement within the frame or the moving camera, whether the trains rolling over the bridge, the bridge’s machinery and steel girders in motion or the abstract design of vertical and horizontal planes. The beauty of modern technology is, of course, another ubiquitous trope of the modernist film avant-garde, as demonstrated by Laszlo Moholy Nagy’s Impressions of Marseille’s Old Port (1929), Eugène Deslaw’s La Marche des machines (1929) and Dziga Vertov’s Man With a Movie Camera (1929), among many others.

Three other city symphonies follow: Andor von Barsy, Simon Koster, and Otto van Neijenhoff’s Fragment Zero to Zero (1928) uses the repeated image of a clock to document human activity in a city over a twelve-hour period, beginning with industrial work and ending with urban leisure time activity. Andor von Barsy’s Hoogstraat (1929) is an “absolute film,” documenting Rotterdam’s famous shopping street, intercutting pedestrians and street vendors with storefronts. The numerous shop window mannequins point to another favorite visual trope, especially of the Surrealists, as inspired by Eugène Atget’s pre-WWI images of Paris. Sadly, Hoogstraat’s picturesque neighborhood was completely obliterated by Nazi bombs in 1940, giving the film added documentary value. Finally, the anonymous and charming Weekday (1932) uses a uniformly subjective p.o.v. camera to illustrate a commuter having breakfast, dressing, then taking a taxi through city streets to work.

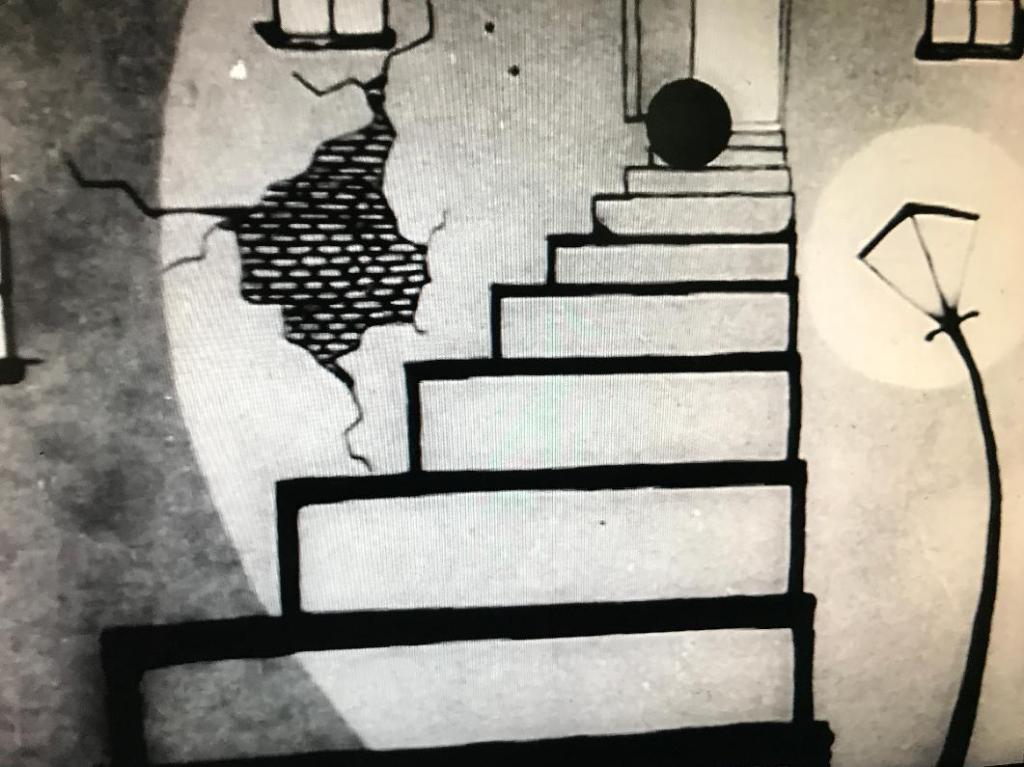

The outlier in the second program is Frans Dupont’s animated Depth (1933), which as the film tells us is “an absolute film about harmony; not a representation of a particular subject.” The film intercuts abstract circles and rectangles, some of which connote an urban landscape, with animated portraits of a man and woman, interrupted by a live action scene of a smoky card game. It is an experiment in creating three dimensions from two, but remains mysterious.

In any case, this excellent primer on the 1920s-30s European film avant-garde is available for viewing through March 9th.