Archival Spaces 385:

Dark Carnival. The Secret World of Tod Browning

Uploaded 31 October 2025

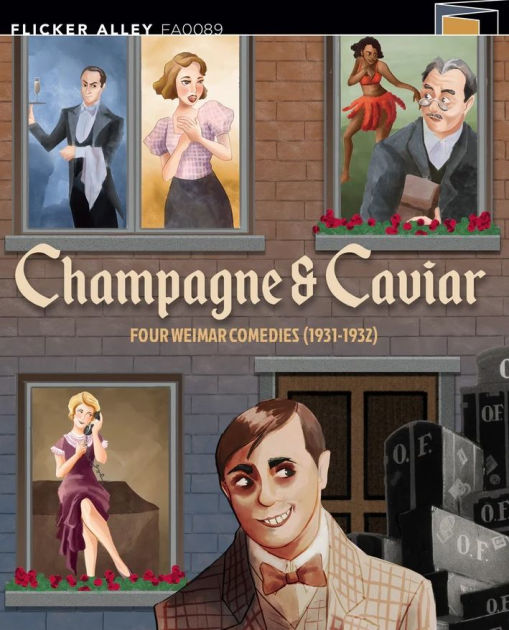

Beginning with D.W. Griffith, but certainly after the Supreme Court’s decision in Mutual Film Corp. v. Industrial Commission of Ohio (1915), American film directors and studios were obsessively and aggressively optimistic in their depiction of an American imaginary. In that landmark case, negativity, social comment, and political commitment were not protected by the 1st amendment. Tod Browning saw the dark side, as did many European filmmakers, even before German Expressionism became the template; film noir followed almost two decades later in Hollywood, its light and shadow, its ambiguity and uncertainty significantly influenced by German-speaking Jewish exiles. Yet Browning was anything but a European, in practice; indeed, his thematic consistencies and unique imagery represented a total anomaly in the silent and early sound film era in America.

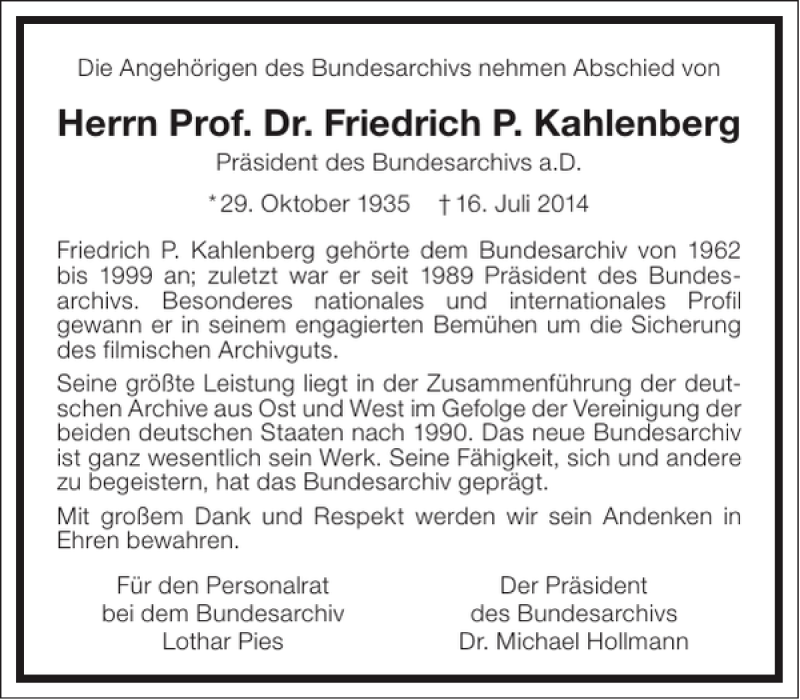

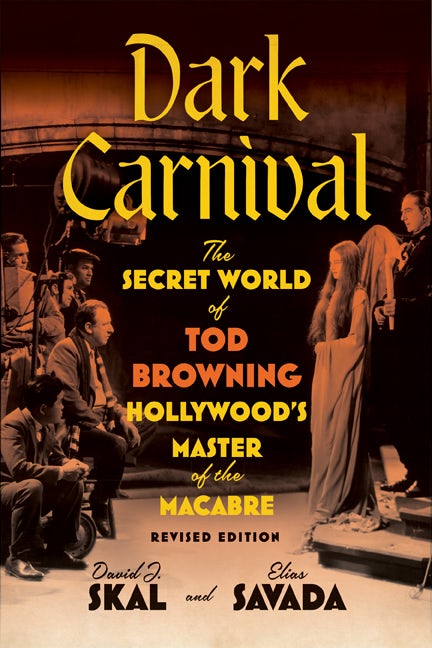

When I was a post-graduate intern at George Eastman Museum in the 1970s, I was able to see several Tod Browning’s MGM films with Lon Chaney, some of which my boss James Card had acquired from the Cinémathèque Française, like The Unknown (1927), while several other Chaney films had been deposited directly by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, like The Unholy Three (1925) and The Blackbird (1926). I had seen Dracula (1931) and Freaks (1932) in college at revival houses, like the TLA in Philadelphia, on South St., but was still unprepared for the gruesome and seemingly amoral spectacle of Chaney’s silent melodramas, especially the armless knife-thrower of L’inconnu. While the Browning revival was just getting underway, The Unknown and The Unholy Three were not yet available to the public. It would take another two decades before Dark Carnival. The Secret World of Tod Browning. Hollywood’s Master of the Macabre by David Skal and Elias Savada, published in 1995, called attention to Browning’s 1920s oeuvre. It has now been reissued in paperback in a revised edition by the University of Minnesota Press. Originally based on numerous interviews conducted by Savada in the 1970s when many contemporaries of Tod Browning were still alive, the new edition incorporates information from Browning’s personal scrapbooks and photo archives. Tragically, David Skal never saw his revised work in print.

David and I were a little more than colleagues, but a little less than friends. I met him in 1998, when I was the founding Director of Universal Studios’ “Archives & Collections,” and the studio was preparing the release of the new “Universal Monsters Classics Collection,” during which we both recorded several film interviews for the release. David was already the world’s expert on Dracula, having published Hollywood Gothic: The Tangled Web of Dracula from Novel to Stage to Screen in 1990 and The Monster Show: A Cultural History of Horror in 1993. At Eastman in the 1980s, I knew Elias Savada because of his work on the AFI catalogues and his close association with my mentor, George Pratt. I never got around to reading their Dark Carnival, maybe because it was published after I left for Munich. Over the years, I stayed in touch with David Skal, invited him a couple of times to lecture in my film history classes at UCLA and Chapman, especially when we could discuss non-academic film history careers. Eli and I became friends, attending AMIA conferences and bunking up.. It was, therefore, a major shock when the news spread that David and his long-time partner had been killed by a drunk driver in Los Angeles on New Year’s Day 2024. In July, Eli stayed in our guest house when we both attended David’s memorial in Descanso Gardens in La Cañada.

As David Skal argues in Dark Carnival, Tod Browning’s penchant for the weird, macabre, and downright perverse was cultivated during his long apprenticeship in carnivals, circus side-shows, and burlesque houses, always a transient and social outcast. Born in Louisville in 1874 (or 1880 ?), Browning entered the film industry under fellow Southerner D.W. Griffith in 1913, acting in wild melodramas and comedies, then transitioning to directing in 1915 at Reliance/Mutual with the one-reeler, The Lucky Transfer. Browning followed Griffith to Triangle in 1917, a brief stint before joining Metro Pictures the same year, then landing at Universal. There, he met Irving Thalberg and Lon Chaney, who would both heavily influence his career in the next ten years. Browning and Chaney’s first film together was The Wicked Darling (1919), a Priscilla Dean programmer about pickpockets. Crime would become Browning’s preferred genre. Browning, Chaney, and Dean were reunited in Outside the Law (1920), a story of jewel thieves and double crosses that catapulted all three to fame. But it was with The Unholy Three, featuring a criminal gang made up of a ventriloquist, a strong man, and a cigar chomping baby that Browning hit his stride, creating macabre melodramas that rivaled The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920), expressionist shadows and all. Browning was the only American director to even obliquely address World War I’s legacy of physically deformed bodies and minds, which Tony Kaes tells us is also the trauma behind German Film Expressionism.

The Chaney-Browning freak shows continued with The Mystic (1925), The Blackbird, The Road to Mandalay (1926), The Show (1927), The Unknown, and the lost London After Midnight (1927). As Skal/Savada note: “The sadomasochistic tone pervading the Browning-Chaney collaborations raises legitimate questions about the private psychologies that together generate such cruel public spectacle.” (p. 114) Happily, the authors discuss Freud’s shadow in oedipal plots, but eschew any psychoanalysis of the Browning.

Browning’s film career experienced a slow downward slide in the sound era, despite two masterpieces, one a worldwide hit, Dracula, the other a miserable flop, Freaks. Skal notes that both films were recapitulations of his prior films, his dandified and theatrical Dracula owing more to his music hall magicians than to Stoker or Murnau. Freaks‘ amalgamation of actual, deformed side-show actors was far too much realism for 1930s audiences, the film not finding an audience until its revival in the 1960s. Indeed, the sensibilities of Browning’s films were astonishingly modern fueling the Browning revival almost forty years after his career ended: To quote Skal/Savada: “Browning brings us the bad news attendant on the most technologically advanced country in history, which is simultaneously the cruelest.”(p. 265) This book is a must-read for anyone interested in American cinema, not just horror.