Archival Spaces 280

Giornate del Cinema Muto 2021 Online

Uploaded 15 October 2021

This is the 40th anniversary of what is now the oldest silent film festival in the world. I attended my first Giornate del cinema muto in Pordenone in 1988, when I accepted the Jean Mitry Award in the name of George Pratt, the long-time curator at George Eastman Museum. I have attended a little more than half of the subsequent festivals, and reviewed or blogged about a third of those I attended. While last year’s festival was completely online, due to the COVID pandemic (see Archival Spaces 254), this year I have again only been able to partake virtually, even though the Festival does have a live component. Unfortunately, given problems with the link, I also missed the first online presentation, The Joker (1928), a Danish film directed by German George Jacoby and produced by the Nordisk, but shot in Nice with an international cast.

I did see the following program of mostly eccentric short films. Soap Bubbles (1911, Giovanni Vitrotti) was interesting because of its use of bubbles to insert didactic images into the frame that lead to the reformation of a bad boy. Cinderella (1913, Eleuterio Rodolfi) features many scenes of actual film production at Ambrosia studios, and thus parallels Asta Nielsen’s contemporaneous Die Filmprimadonna. Bigorno fume l’opium (1914, Roméo Bosetti) uses a host of cinematic special effects to simulate an opium dream. But my favorite was a stop-motion Italian animation, The Spider and the Fly (1913), in which a little boy pulls the wings off a fly, leading to a madcap chase, during which the courageous little fly consistently outwits the spider.

The Australian melodrama, The Man From Kangaroo (1920, Wilfred Lucas) was also interesting as an Aussie Western, starring Snowy Baker, an Olympic swimmer, boxer, and all-around athlete, who plays a boxing vicar in this Aussie western in the Outback of New South Wales. Baker apparently brought former Griffith actor and director Lucas and his scriptwriter wife, Bess Meredyth, to Australia for the production of this and two subsequent films. The story is slight and the plot has several large holes, but the action on horseback and scenery make up for those deficits.

Bess Meredyth was an important scriptwriter in silent Hollywood and as Giornate director Jay Weissberg notes in his introduction, the Festival this year is focusing on women filmmakers, including the lesser-known Agnes Christine Johnson, who wrote the script for Charles Ray’s An Old Fashioned Boy (1920, Jerome Storm). While Johnson had a very long career in Hollywood, her only claim to real fame may be Lubitsch’s Forbidden Paradise (1924) and several of the Andy Hardy films in the 1930s. Except for the bucolic charm of The Old Swimmin’ Hole (1921), Charles Ray’s work is strictly at the level of programmers, and this film with its low budget set is no exception. Indeed, it is chiefly interesting, because it was made shortly after our last major pandemic, the Spanish Flu, had waned, and is here referenced for comedic effect.

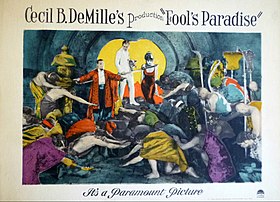

At a completely different level is Cecil B. DeMille’s Fool’s Paradise (1921), which features a script by Sada Cowen and Beulah Marie Dix., two more prolific women writers. Starring Conrad Nagel, Dorothy Dalton, and Mildred Harris, the melodrama about an unsuccessful blind poet moves from the gritty oil fields of West Texas to the exotic Kingdom of Siam with lavish sets and costumes throughout. DeMille takes the saying love is blind literally in a tale of a man chasing an illusion of womanhood because it suits his vanity while ignoring the real love of a woman willing to sacrifice all. Interestingly, there are no real villains in the piece, even if Theodore Kosloff’s Mexican saloon proprietor skirts a nasty racial stereotype, but is sympathetic in his unrequited love for Dalton.

A Public Prosecutor and a Teacher (1948, Yun Dae-ryong) is an anomaly in the Pordenone program, a silent film produced in Korea after World War II and the end of Japanese occupation, when the lack of sound film equipment forced filmmakers to shoot 16mm without sound. The film concerns a kind-hearted teacher who takes a poor orphaned student under her wing and is repaid years later when as a public prosecutor he pleas for acquittal in a murder charge, in which she is falsely accused. While a somewhat annoying and over-talkative narrative, voiced by Sin Chul, Korea’s lastbyeonsa (benshi), adds melodrama, the film’s images are perfectly legible. Indeed, the street scenes of Seoul before the Korean War utterly destroyed the city have historical value in and of themselves, while the acting is effective, especially Lee Yeong-ae as the young teacher. Given the sophistication of Korean films and television in the last decade, this is an exciting find.

Phil for Short (1919, Oscar Apfel), based on Clara Beranger’s proto-feminist script, starts out like a Griffithian melodrama with a nosy, church-going matron trying to clip the wings of Sapphic free-spirit Damophilia Illington, Phil for short, who farms in pants and dances à la Isadore Duncan in flowing Greek gowns. Like Duncan, her choreography comes from Greek art and her father. But this is a comedy of woman’s empowerment and agency, so when her father, an impoverished Greek professor dies, and she is threatened with marriage to a man twice her age, she seeks refuge in the arms of a younger Greek professor, who is a misogynist. After more complications, she turns him and all ends well. Apfel’s film is a mixture of archaic film style and modern feminism with more than a few gay winks. Two years later, Beranger would script William de Mille’s Miss Lulu Betts (1921), a masterpiece of feminism, discovered in Pordenone years ago, and then became the director’s steady screenwriter and wife.

Ellen Richter was a hugely successful actress in Weimar Germany, who with her husband Willi Wolf, produced lavishly crafted comedies and adventure films, yet fell out of film history because her films were popular entertainments. A self-assured young flapper with short hair, the actress teaches the stodgy burghers of a hypocritical small town a lesson in Moral (1928, Willi Wolf) they won’t forget after the “Morality Society” disrupts her theatrical revue with noisemakers and demand she be driven out of town: she films them as they surreptitiously visit her for a “piano lesson.” Although based on a pre-WWI play (1909) by Ludwig Thoma who made a career of satirizing Bavarian provincial life, the film references contemporary politics in that Nazi thugs were known for upending film and theatre performances with just such noisemakers. Another delight in this expensive UFA studio production is seeing Berlin’s famous “Tiller Girls” troupe in an extended clip, which popularized synchronized dancing – the Tiller Girls had originated in London in the 1890s – and became the model for the Rockettes.

Maciste in Hell (1926, Guido Brignone) is the 13th and last appearance of Bartolomeo Pagano as Maciste and is considered one of the best, after he first appeared as Axilla’s slave, a secondary character in Giovanni Pastrone’s Cabiria (1914), before becoming a hero in subsequent films. Italy’s sword and sandal epics from the pre-World War I period had put the country on the cinematic map, giving the world feature-length films for the first time, and Maciste all’ Inferno still clings a bit to that aesthetic with its tableau-like framing, lack of dynamic editing, and posed acting. Based on the costumes, Maciste is now living in a Biedermeier version of Italy – shades of Caligari and The Student of Prague – and travels to Hell after he and his female neighbor are harassed by a contingent of devils, dedicated to taking their souls. It is the insane sets, imaginative costumes, and riotous make-up of Hades, tinted in red and other hellish colors that make this film such a pleasure, complimented by a truly wonderful new orchestral score by Teho Teardo.

We can credit Ellen Richter’s rediscovery to Oliver Hanley and Philipp Stiasny, young German film historians no longer beholden to the intellectual prejudices of the past. Like many other absent Pordenone regulars, I regret not seeing more of the Ellen Richter films, shown at the Festival live. But hopefully next year.