Archival Spaces 300

Tel Aviv Symposium: A Film Scholarship Without Films?

Uploaded 21 July 2022

Back in the early 1980s, my colleague and friend, Ute Eskildsen, and I organized an exhibition and published a catalog on Helmar Lerski, the New Realist photographer in Weimar Germany and a pioneering filmmaker in Jewish Palestine. Out of that research, a historical essay grew, “Zionist Film Propaganda in Nazi Germany” that described German-Jewish filmmakers involved in Zionist propaganda filmmaking in the 1930s, after their expulsion from Berlin; for the project, I conducted research in the World Zionist Archives in Jerusalem and combed through microfilms of German Zionist newspapers. I was continually reminded of that work while attending virtually the symposium, “A Film Scholarship Without Films? Reimaging the History of Israel Cinema Culture Through the Archive,” held at the Steve Tish School of Film and Television at the Aviv University on 5-6 July 2022.

Taking its dictum from Eric Smoodin’s seminal essay “As the Archive Turned: Writing Film Histories without Films,” which describes American film studies’ historical turn in the 1980s to archive research-based film history, the Symposium hoped to effect a similar sea change in Israeli film studies. According to conference organizers Dan Chyutin and Yael Mazor, conventional narratives of Israeli cinema history have relied almost exclusively on close readings of the films themselves. In contrast, a cinema history based on archival research, on the analysis of advertising, posters, company production records, balance sheets, interviews, and other non-filmic documents would result in a much richer history of Israel film culture that could also gauge the cinema’s impact on larger political issues.

Chyutin in his following conference presentation analyzed Israeli film fan magazines to theorize that these publications deviated from the austere 1950s Zionist project of national sacrifice to embrace the consumerist ideology of Hollywood. Next, Boaz Hagin details film theoretical, technical, and practical discourses in modernist Hebrew language art magazines, contrary to the conventional narrative that Israel film discourse prior to 1970 had been a wasteland. Olga Gershenson, on the other hand, discussed her research methodology in researching the production, distribution, and exhibition of an Israeli horror film wave post-2010.

Giora Goodman began the next panel with an analysis of the Israeli Foreign Ministry’s film politics, which again a counter-narrative theorizes that they were more interested in international commercial hits than in Zionist propaganda, which meant only films about the Arab-Israeli Conflict; that sold tickets abroad. Naomi Rolef and Hilla Lavie described archival documents, specific to their research. Rachel Harris’ contextualized close reading of Menachem Golan’s film noir thriller Eldorado (1963), Elad Wexler’s reconstruction of script changes, both aesthetic and political, in Hole in the Moon (1965), and Iddo Better Pocker and Orit Rozin’s dissection of the commodification of Israeli history in Manahem Golan’s Operation Thunderbolt (1978), all argue that these films existed outside the box of the Zionist project.

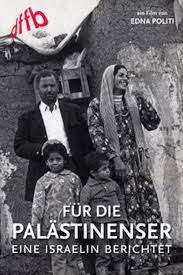

In the final session, Israela Shaer-Meoded analyzed the film career of Palestinian-Israeli filmmaker Edna Politi, whose 1973 film about the Yom Kippur War is known throughout the world, except in Israel. Finally, David Shalit contrasted Menachem Golan’s own constructed legend of his film career with the reality of Golan’s Americanization.

Wednesday morning began with a panel on Israeli film censorship issues. Jonathan Yovel began by noting that there is no general theory of censorship because cases are too varied, but that censorship records tell us not only what is removed from public review, but also the taboos and obsessions of a culture, then discussed a number of foreign film censorship cases, noting that the Israel State Censorship Board’s decisions were often completely arbitrary. Ori Yaakobovich followed up with the more than two-decade-long struggle to get Oshima’s In the Empire of the Senses approved for public screenings in Israel, due to the Board’s intransigence in regards to sexual content.

The remainder of the symposium was largely informational. The late morning saw a roundtable of film archivists from the Israel Film Archive, the Steven Spielberg Jewish Film Archive, the Yad Tabenkin Research Center, the Tel Aviv Cinematheque, the University of Texas Library, and the Israel Testimonial Database, discussing methods of access and contents in their respective archives. In the afternoon, Christian Olesen and Sarah Dang introduced the digital databases of the Amsterdam Desmet Collection of early cinema and the Women Film Pioneers Project, respectively. While the former includes films and metadata, the latter offers biographical information, as well as numerous analytic visualizations of the data.

The symposium concluded with Eric Hoyte’s keynote in which he introduced various American film magazine databases, including Lantern and the Media History Digital Library. The construction of such digital archives depended on 1) what kind of research questions govern them, 2) Which historical sources are potentially available, and 3) what kind of inter-disciplinary research collaborations can such databases generate.

As the conference amply demonstrated, archival research is clearly migrating to cyberspace with ever more magazines and other paper documents becoming available. Israeli scholars are therefore much better equipped to make the historical turn, than American film historians three decades ago, when historical research still meant traveling, e.g. to the Jewish Agency in Jerusalem, as I had to do in the early 1980s.