Archival Spaces 308

Rachel Maddow’s Ultra Podcast

Uploaded 11 November 2022

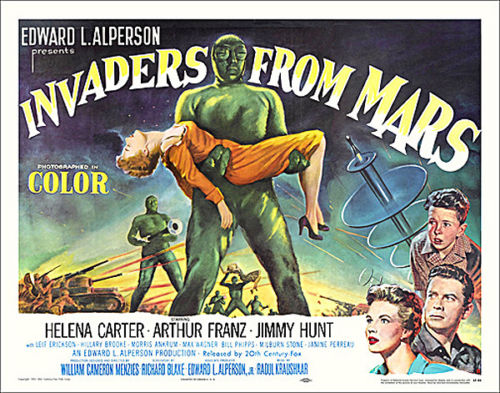

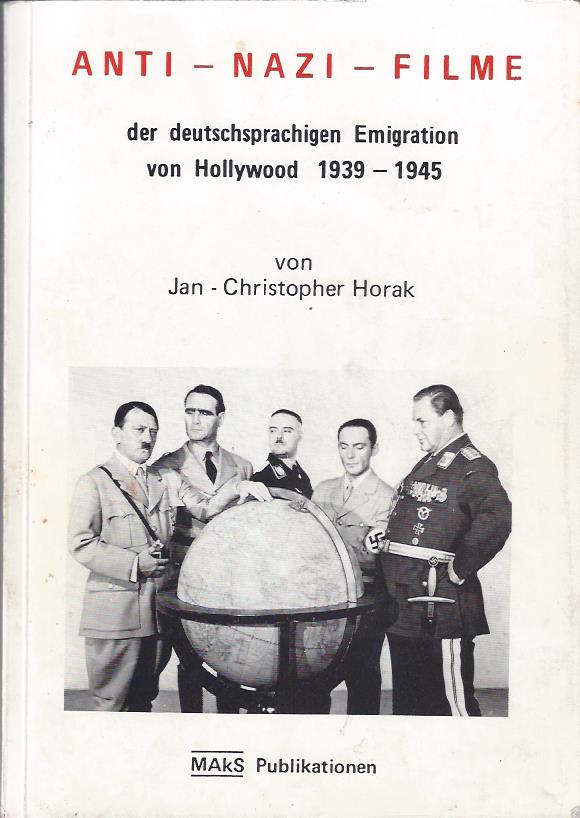

I’ve been listening to Rachel Maddow’s podcast, “Ultra,” narrativising the activities of home-grown American Fascists in the immediate pre-World War II period who openly supported and even carried out terror acts for the Nazi government of Adolf Hitler. The podcast has reminded me of “The Fifth Column” chapter in my dissertation, Anti-Nazi-Films in Hollywood, which analyzed Confessions of a Nazi Spy (1939, dir. Anatole Litvak), among other films. The term 5th column had been coined during the Spanish Civil War to explain how Franco’s Fascists had conquered Madrid with four military columns from the outside and a fifth column from inside. While some contemporary critics maintained that Hollywood’s anti-Nazi-Films were crude propaganda, their visualization of Nazi activity was not exaggerated; Maddow’s “Ultra” demonstrates that the threat of a white nationalist, anti-Semitic cabal in America was much greater than any Hollywood screenwriter could ever have imagined. Maddow could have started her podcast with the back story to Confessions.

The Confessions of a Nazi Spy was based on an actual trial in October 1938 of members of the German-American Bund in New York, the Hamburg-America shipping Line, and the German Embassy in Washington, D.C. The pro-Nazi German American Bund, organized into fifty-five chapters around the country, staged huge rallies at Madison Square Garden and elsewhere, where funds were collected for the Reich. However, of the 18 accused conspirators, only four were found guilty, while the American press seems to have treated the case rather lightly, grossly underestimating the threat. Warner Brothers began working on a film, even before the trial ended, even though the German Consul tried to stop the production and cast members were threatened with death by native rightwingers. The film, starring Edward G. Robinson as FBI investigator Leon G. Turrou and Francis Lederer as the German-American spy, opened on 28 April 1939 and caused a sensation. The film cleverly melds a spy story with both real and staged footage of Nazi Party activities in Yorkville; a prologue was added for the 1940 rerelease, consisting of newsreel footage of the Nazi Blitzkrieg. Unlike the real trial, Litvak’s film chose a happy end with the conspirators behind bars and American Democracy saved. At the box office, the film fared poorly. Nevertheless, Hollywood had made a film that was overtly political, explicitly partisan for American Democracy, and against the influence of Nazism or its American base. American critics complained that it was overly propagandistic. Like the journalists covering the trial, film critics remained complacent to radical right-wing activity in America. Once World War II began five months after the film’s opening, attitudes would begin to change in the USA.

Rachel Maddow’s “Ultra” podcast begins with the plane crash of Minnesota Senator Ernest Lundeen on 31 August 1940, who had been working closely with and getting paid by Nazi agent George Sylvester Viereck to keep America out of the war in Europe, even writing Lundeen’s speeches for him. On her website, Maddow reproduces one of those speeches: “The leaders of the movement to get us into war, employ falsehoods as their most deadly weapon… Thus an entirely false picture is created in the mind of the American public, as if Hitler actually threatened to descend on the United States.” But it wasn’t just speeches by isolationist senators, like Burton Wheeler and Gerald Nye that were a threat, it was actual violence.

In the next podcast, Maddow reveals the plans of Father Charles E. Coughlin’s Christian Front to create a militia armed with military-grade machine guns to overthrow the government and bomb Jewish and “communist” businesses. Eighteen members were arrested in January 1940, but again the Justice Department bungled the case so that 9 of 13 defendants were acquitted and a mistrial declared for the rest. It would take the government four more years to put together another case against the Christian Front. The trial opened in April 1944 with sheer pandemonium in the Court, what with initially 30 accused and 22 separate defense teams all screaming at once. But that prosecution, too, would explode. But I get ahead of Rachel.

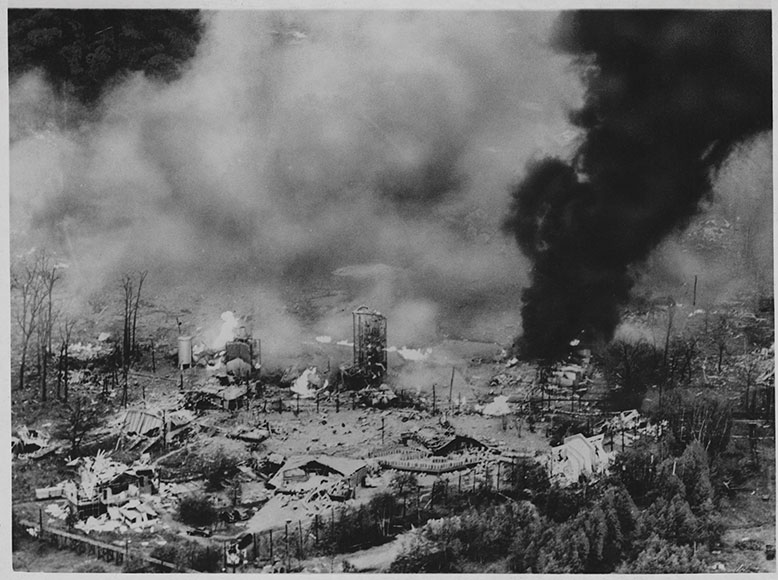

While episode 3 begins with a terrible act of right-wing sabotage at a Hercules Powder Plant in Kenvil, N.J. on 12 September 1942, killing 52 and injuring 125, and destroying 30 buildings, it mostly concerns the efforts of a private citizen, Leon Lewis. An L.A.-based Jewish lawyer, Lewis in 1933 began documenting subversive activities by American white nationalist groups in Los Angeles, like William Dudley Pelley’s Silver Shirts (Silver Legion of America). When he went to the law, the L.A. Police sat on their hands, stating they saw no threat. On 12 November 1942, three more munitions factories were blown up, killing 16 more people, but no one was ever arrested in the aftermath of either act, even though the FBI had evidence of involvement by pro-Nazi groups.

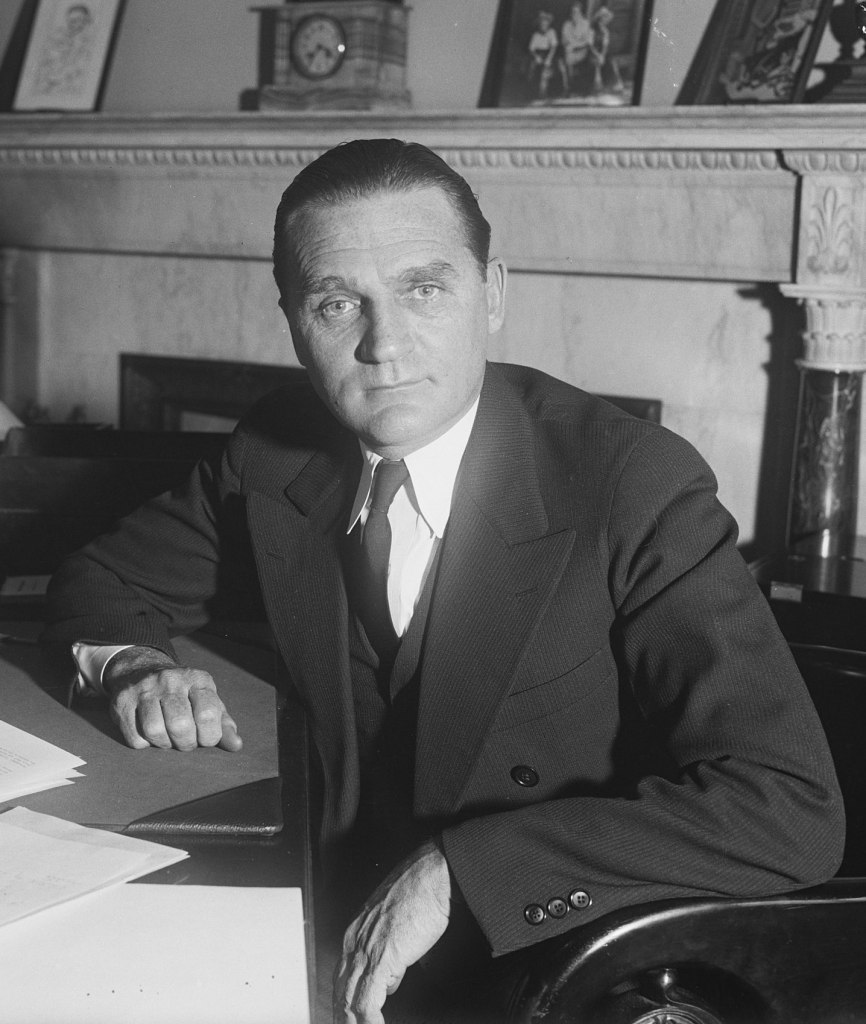

Episode 4 takes up the story of Ernest Lundeen again, showing the way Lundeen and numerous other members of Congress supported the Nazi cause by forming the America First Committee. Nazi agent George Sylvester Viereck actually paid dozens of members of Congress to send millions of pieces of Nazi Propaganda, printed and paid with taxpayer dollars, through Congress’s free mail service. While the Justice Department named a special prosecutor, William Power Maloney, to investigate Viereck and members of Congress, including Rep. Hamilton Fish (NY) who had willingly misappropriated government funds for Nazi propaganda but Burton K. Wheeler and other America First’ers used their influence to get Maloney fired and shut down the investigation after a grand jury had convened.

But Justice did not close down the investigation, it hired a new special prosecutor, John Rogge who widened the investigation, and gave it focus, indicting the Christian Front insurrectionists for sedition (although Congressmen were spared); they had conspired to overthrow the government by undermining the armed forces in time of war. That four-year prosecution ended in a mistrial when the trial’s verbal violence literally may have killed the judge.

Maybe in future episodes, Rachel Maddow will reveal why the U.S. government has consistently failed prosecutions of right-wing terrorists, but been so successful at prosecuting leftists? Hopefully, she will also reveal why the present crop of seditious Trump insurrectionists in Congress have avoided prosecution or even real scrutiny.