Archival Spaces 312

Murray Glass – Em Gee Film Library

Uploaded 6 January 2023

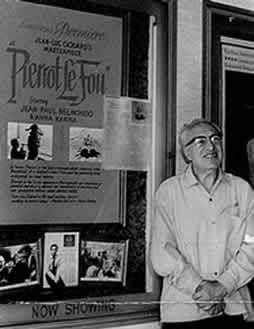

I’ve been thinking about Murray Glass for the last couple of months because I had planned to interview him for a blog, only to realize that he had died in 2019 shortly before the pandemic started, completely forgotten, certainly without any recognition of his passing in the media. Murray Glass owned and operated Em Gee Film Library, a 16mm film distributor which was in business for more than fifty years. I knew Murray for approximately 30 years, first as a client when I was researching my Lovers of Cinema on the early American avant-garde, later as a colleague and sympathetic ear after I moved to Los Angeles and became Director of UCLA Film & Television Archive. The role of film collectors and 16mm film distributors in the history of American film preservation has yet to be written, although Dennis Bartok’s A Thousand Cuts (2016) makes a good start.

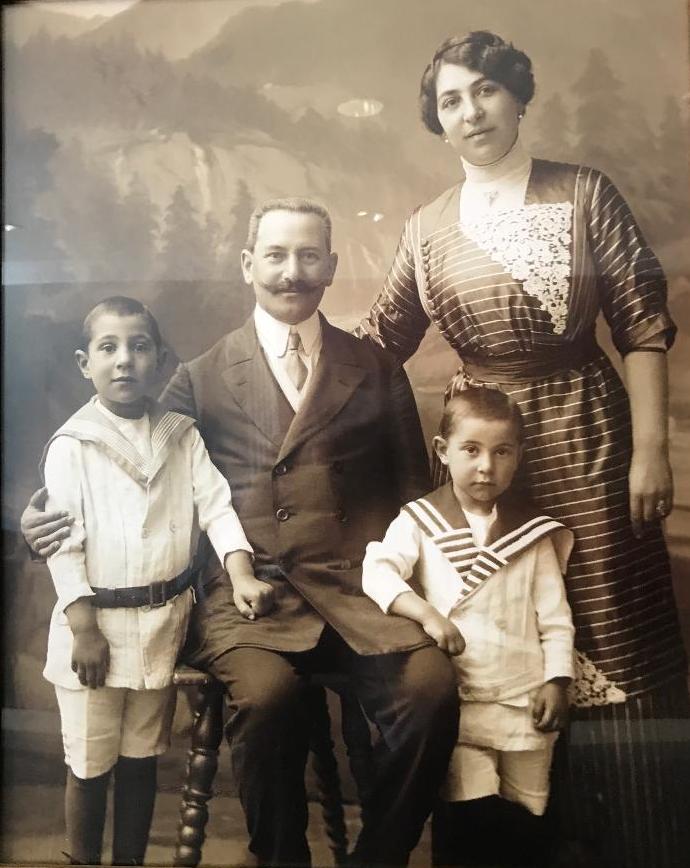

Murray Glass’s Jewish parents were Solomon and Celia Glass who had emigrated in their twenties in 1921/22 from Ostrołęka, Poland to New York, and were living in the Bronx when Murray was born on 25 October 1924. We know from the 1950 census that young Murray gave his profession as a musician and was still living in the Bronx, but no longer with his parents. By then Murray was also a film collector. His father had given him a 16mm film projector with a handful of short films in 1937. He was in the U.S. Army in 1945/46. In 1946, Murray took avant-garde filmmaker and artist Hans Richter’s film course at City College of New York, lending Richter a couple of Chaplin shorts for class; weeks later he received a $ 10.00 check in the email, which constituted his first film rental. In a 1995 L. A. Times article, he said, “I began going to the Museum of Modern Art, and I became a film junkie.”

It would not be until 1962 that Murray Glass was able to turn his passion into a profession by founding Em Gee Film Library and quitting his day job as a chemist. He had also moved to Los Angeles in 1951 and married in 1952. Shortly after starting Em Gee, Glass got a call from a film professor friend who asked whether Fritz Lang could come over to see Murray’s print of Lang’s M (1931). As Murray enthused in the Times article: “… here was this famous director in my house. I took it as a sign. I felt like a million dollars.”

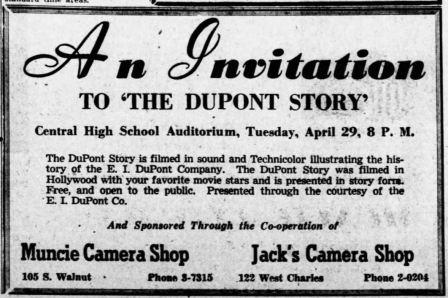

As a lover of American silent film, Murray probably grew his collection by purchasing public domain material and then renting it out. According to Em Gee film catalog 83: “the direction of our effort… (is) namely to offer one of the finest collections of historical films currently available, to which we are making daily additions.” While this sounds like salesmanship, the fact is, Glass had an astonishing breadth of historical films in all genres. With over 6,300 titles at its peak, the film library spanned the years 1893 (Edison’s Fred Ott’s Sneeze to 1965 (Roman Polanski’s Repulsion). The catalog featured Charlie Chaplin films from his Keystone, Essanay, and Mutual periods, Fatty Arbuckle, Buster Keaton, Harry Langdon, Laurel and Hardy, D. W. Griffith, as well as silent and sound features, American and foreign, like De Mille’s King of Kings (1927), Cavalcanti’s Dead of Night (1945) and Francis Ford Coppola’s Dementia 13 (1963). It is an extremely eclectic collection, and I suspect Murray distributed any film he could get his hands on, when duping prints were not protected by copyright, including exploitation films about drug use and some blue movies. Murray claimed that „he acquired whatever there was a demand for.“

He also distributed newsreels, documentaries, silent and sound animation, and avant-garde shorts from France, Canada, and the United States. My first contact with Murray was in the early 1990s, when I purchased a print of Boris Deutsch’s Lullaby (1925), for the George Eastman Museum. It was a film I could find nowhere else when researching the early American film avant-garde, and it illustrates the bridge Murray Glass and other 16mm film distributors played in preserving American film history, when few public institutions, other than GEM, MOMA, and Library of Congress were engaging in such film preservation efforts. The print was in very good condition – who knew about the film – so I designated it a master positive for preservation, not to exploit it, but to guarantee its survival.

Murray was proud of the fact that he had found a 1907 one-reel version of the Kalem Film Company’s Ben-Hur, purchasing a 35mm nitrate print at auction and donating the original film to the Museum of Modern Art, while distributing 16mm reduction prints. Glass also claimed credit for preserving Max Fleischer’s feature animation, Evolution (1923) from a tinted and toned nitrate print, he distributed most of Fleischer’s output from Koko, the Clown, and Betty Boop to Popeye, but also Lotte Reininger’s German films. Em Gee Film was unique in that Murray Glass emphasized film preservation in his introduction to catalog 83: “… because of a variety of factors including carelessness, indifference, greed, and economics, much of our film heritage has long since disappeared into either dust, gummy messes, or disastrous nitrate conflagrations.”

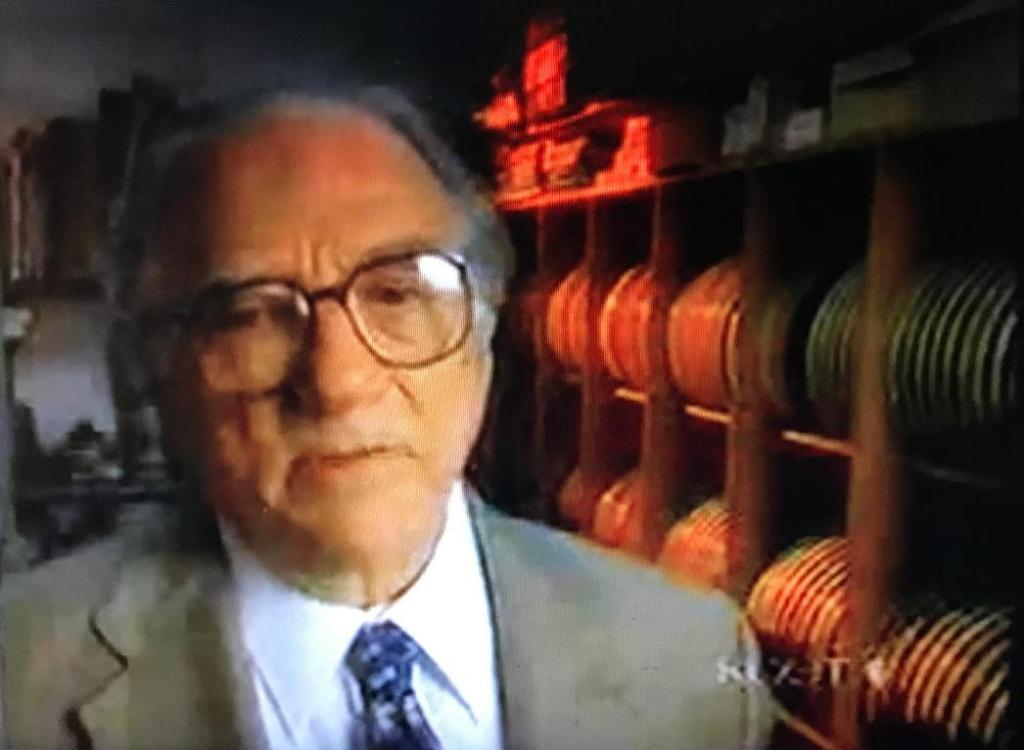

By the time I got to UCLA in 2007, Glass was shopping the collection around. He was asking $ 1.25 million, which according to most experts was over-valued. I went out to see the Em Gee Film Library sometime in 2010; Murray knew the Archive could not buy the collection, but he was hoping an “angel“ could be found to purchase the collection and donate it. In a KCET-TV interview on Life & Times, Glass noted that “universities interested in the collection plead poverty.” My “angel” wasn’t interested. David Sheppard eventually purchased the entire collection in 2011 for Blackhawk Films – now owned by Serge Bromberg’s Lobster Films – with the proviso that Murray could still access his negatives – deposited at the Academy Film Museum – for occasional collector’s prints as long as he was alive. Another proviso was that the used distribution prints would be donated to the Niles Essanay Silent Film Museum in Fremont, CA. According to an email David sent to Serge Bromberg on 22 January 2011, “This is the most extravagant gesture I have ever made. I could have bought a nice house plus a new car for the money. Let’s hope that the Museum endures for a long, long time.”

Murray Glass died in Van Nuys, CA. on 27 September 2019. It is good to know that his legacy will live on at Niles and in Lobster’s preservation of some gems from the Em Gee Film Library.