Archival Spaces 389:

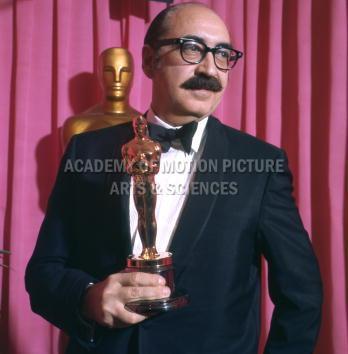

Saul Bass wins an Academy Award

Uploaded 26 December 2025

Ten years ago, in 2015, I published Saul Bass: Anatomy of Film Design, a University of Kentucky Press book, a French edition arriving seven years later. Not many people know that George Lucas worked for Saul and accompanied him to the 41st Academy Awards, where Bass won for Why Man Creates. Behind the scenes, there was turmoil.

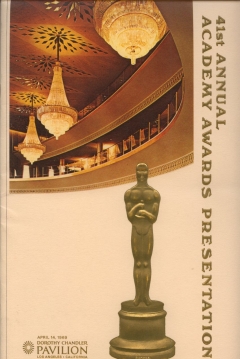

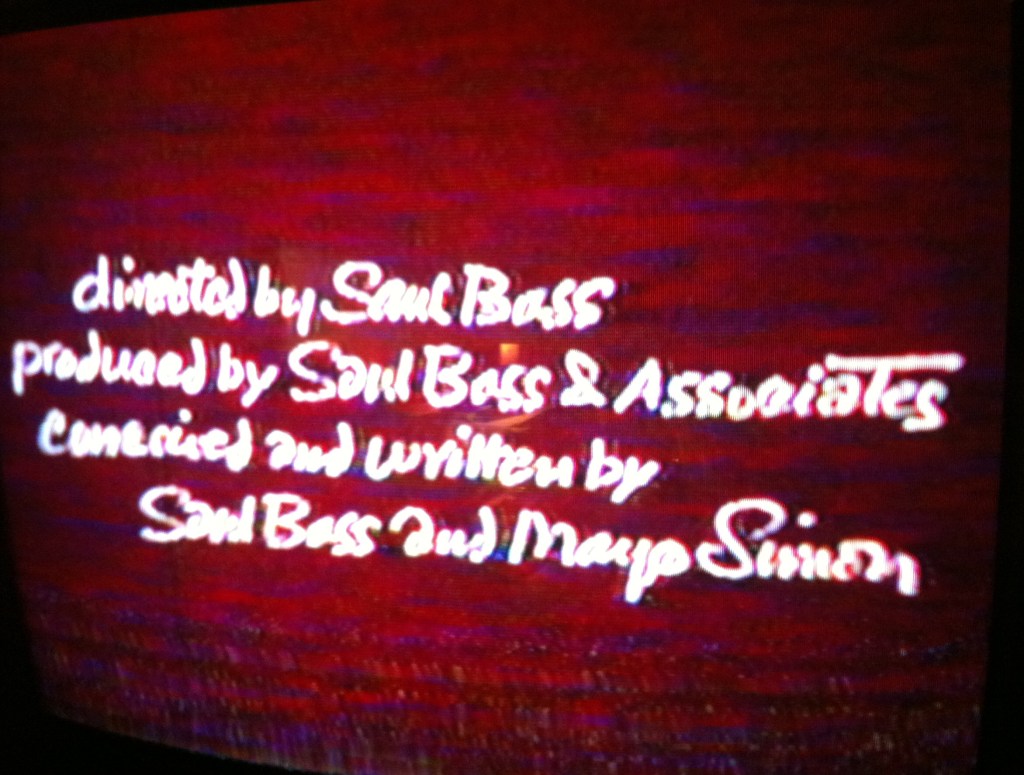

The Forty-First Academy Awards ceremony took place on 14 April 1969 at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, on what used to be Bunker Hill in downtown Los Angeles. It was the first Oscar ceremony to be broadcast worldwide and the first held at that location. As usual, it was a star-studded affair. Katharine Hepburn was nominated as best actress for the second year in a row, this time for The Lion in Winter, an award she would have to share with Barbra Streisand for Funny Girl—the only time there has been a tie in this category. Saul and Elaine Bass, too, were present at the awards ceremony, the designer nominated in the “best documentary short” category for Why Man Creates (1968). The couple rode to the Chandler in a rented limousine together with USC graduate student and Bass advisee George Lucas, who had been an assistant on the production. Lucas would never work for or with Bass again, but he gave strong public support to Quest (1983, Saul Bass). Bass’s competitors for the Academy Award were The House that Amanda Built (Fali Bilimoria), The Revolving Door (Lee R. Bobker), A Space to Grow (Thomas P. Kelly Jr.), and A Way out of the Wilderness (Dan E. Weisburd). Given his longtime work in the film industry, Bass was heavily favored to win.

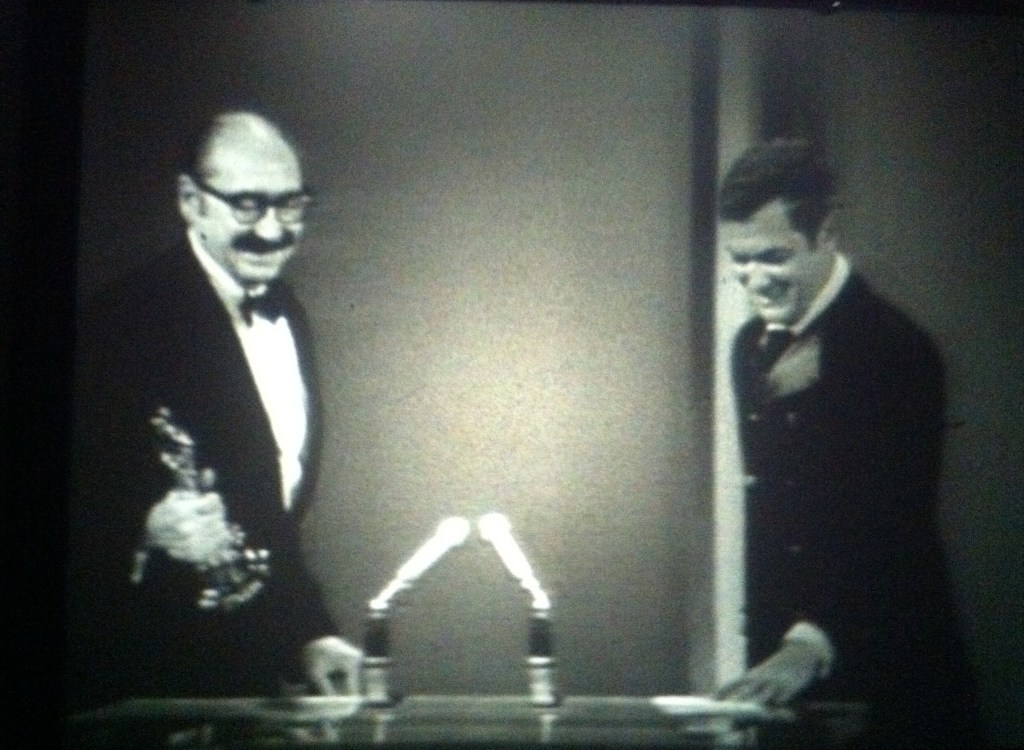

At the ceremony, Bass sat in an aisle seat at stage left, ten rows from the podium; Elaine was next to him in a light-colored chiffon dress. Actors Diahann Carroll and Tony Curtis read out the names of the nominees for best documentary and best short documentary, respectively. When Tony Curtis called out Bass’s name as the winner, he bounced up to the stage, despite the wooden cane that preceded his every step. Curtis handed the Oscar to Bass, who was wearing a traditional tuxedo, in contrast to Curtis’s mod outfit. Bass took the Oscar in his right hand while balancing his weight with his left hand on the cane. He bent over the microphone and, in an uncharacteristic moment of brevity, said, “Thank you, thank you very much.” Then he quickly walked offstage. No thanks to his staff, no thanks to his wife, certainly a co-creator, no thanks to the Academy. More importantly, Bass failed to mention Kaiser Aluminum and Chemical Corporation, the film’s sponsor and original producer, causing a mini-scandal to erupt at corporate headquarters. Did Bass just forget, due to nerves or under pressure, to keep his acceptance speech short? Or was it something else? We will probably never know. The oversight may not have been accidental, however, given the huge fights with Kaiser over the film’s final structure, laboratory costs, and even the title. Bass hated the title because he thought it promised more than he could deliver.

In hindsight, it’s clear that Bass deserved to win for what would be his greatest cinematic achievement, although his largely avant-garde work certainly challenged the Academy’s notions of genre. Indeed, the category “Best Documentary, Short Subjects” hardly describes Bass’s free-form essay, a hodgepodge of film notes that asks many more questions than it answers. And what makes it a documentary? The film includes several forms of animation and mostly staged sequences. Indeed, it is a modernist romp, at moments seemingly incoherent and yet also brilliant in its open-endedness; its fragmentation forces the viewer to engage in the construction of meaning, thus fulfilling the promise of every modernist work to make the audience an active participant. In addition to the Academy Award, Why Man Creates won numerous film festival and other awards, and was placed on the National Film Registry of the Library of Congress in 2002, designating it a national treasure.

But the somewhat tortured production history of the film also points out the pitfalls of having a corporate sponsor for such a personal and highly idiosyncratic project. In Bass’s most cynical evaluation of the film, he admitted to a group of AT&T executives: “I think now that the most creative thing about the film was that I found a rationalization that enabled me to convince the client, to allow me to make the film.” Even if the film was not a direct advertisement for Kaiser, the company covered all the production costs, while corporate executives and Bass often had vastly different ideas about what kind of film they were financing. Bass never wanted to answer the question the title asks; it was antithetical to his work methods, but the sponsors were looking for easy answers that could be sold in the education market. The designer usually argued that because sponsored films didn’t have to sell anything, they were preferable to commercials or industrial film productions, where the filmmaker was at the mercy of the client. But Bass wanted to have it both ways: complete freedom to produce artistic work, and complete financing by a corporate sponsor that would pay all the bills, including a substantial honorarium to support Bass’s office. Unlike most other avant-garde filmmakers, Bass was not willing to self-finance or to take on contract work to pay for his own personal films. After all, Bass had grown up in the Hollywood film industry, where no one invested their own money. Paradoxically, despite the insider status that an Academy Award seemingly represented, Bass remained an outsider in the movie industry.