Archival Spaces 344

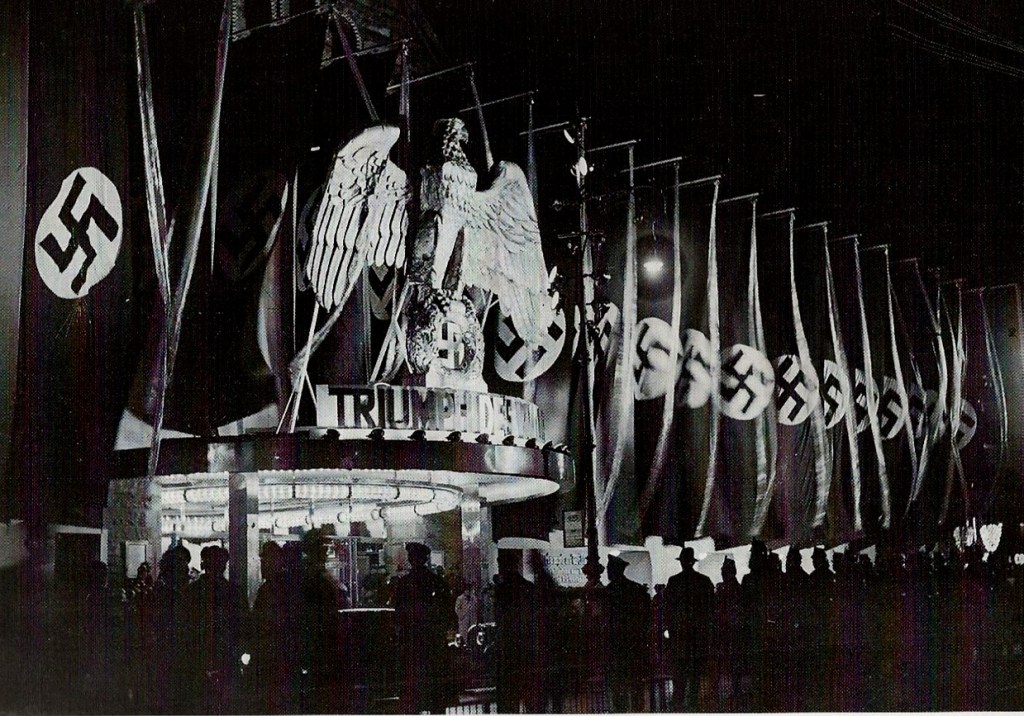

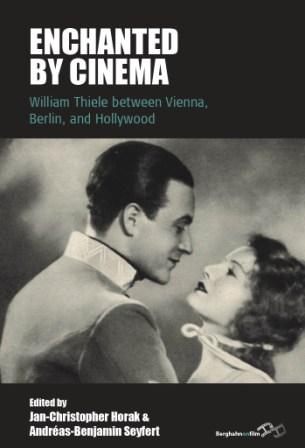

Nazi Film History: Film “Kunst” Film Kohn Film Korruption

Uploaded 5 April 1924

Like most of my fellow film historians, I had never actually read the 1937 Nazi tract disguised as film history, Carl Neumann, Curt Belling, and Hans-Walther Betz’s Film-“Kunst”, Film Kohn, Film-Korruption. Ein Streifzug durch vier Film-Jahrzehnte, although I had mentioned its existence when discussing anti-Semitic policies against German film émigrés. Reading it recently, though, I realized it revealed the dangers we are facing as democrats in America today, because it cloaks hate in political ideology, much like Trump and the MAGA Republicans. The book is not merely a view of film history through the lens of Fascist ideologues, as in the case of the French L’Histoire du Cinéma by Maurice Bardéche and Robert Brasillach, rather Film “Kunst” is viciously and violently anti-Semitic. Finding a copy was not easy, and involved an inter-library loan from an institution on the other side of the country, although I suspect there are more copies available in Germany. It was obviously never republished, other than a 1943 revised edition, printed in gothic German script.

The introduction begins by laying out the book’s goals and parameters as if it were serious, academic work. The authors write they are presenting a cavalcade of four decades of (German) film history, instead of a complete history, while also considering “the political, cultural, civilizational, social, and economic” conditions of film production and reception. That sounds quite reasonable, except by the end of the third paragraph, the authors can no longer contain themselves and claim that their work is also polemical because it removes the veil from Jewish Film Power and Industry, which had until 1933 also controlled the narrative of film history. They then continue their exposé in coded and pseudo-academic language, eventually confessing that their history of German film is also experiential, taking the reader through four decades of battle for a German film free of Jewish influence. The book’s last chapter concludes with what purports to be a brief history of National Socialist cinema but turns out to be an autobiography of Carl Neumann and his father Adolf Neumann, a pioneering cinema owner who opened his first theater in Berlin in 1906, both Kleinbürger filled with white nationalist vitriol.

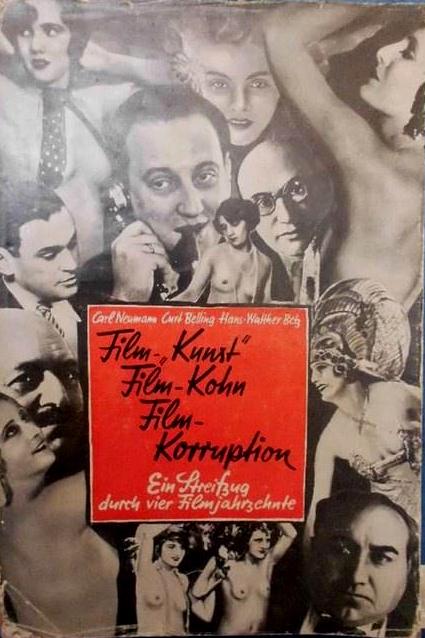

Film Kohn begins not as film history, but as a fiction, „Der Mann mit der Zigarre.” Right after the introduction, “The Man with the Cigar” describes not a real, historical Jewish film producer, but the Jew an sich, a construct of all the most vicious and violent anti-Semitic stereotypes of film producers ever printed. The cigar as the most prominent visual identifier, connoting unwholesome sexual images, class resentments, and economic envy, is backed up a few pages later with visual evidence in six photographs. Chaplin, of course, was not Jewish.

Chapter 2, “How it Started”, rarely mentions names, preferring to traffic in generalizations of technical and economic developments in the medium. But there are a few real names, although their biographies are almost totally fictitious, like Louis B. Mayer and Richard Oswald. Later they mention Constantin David, E.A. Dupont, Leo Mittler, G.W. Pabst, Erich Schönfelder, and Hanns Schwarz as “Ufa-Juden.” The authors are constantly confronted with their own contradictions, their narrative one of the film industry’s incredible growth and influence over daily life, dominated by you know who while making repeated attempts to prove that “they” had nothing to do with the cinema’s accomplishments. Each page is filled with hate, the authors soon enumerating film titles and their makers to prove Jewish dominance, some of which are actual, others completely fictitious, e.g. when they mention a 1930 film production of Jew Süβ, starring Fritz Kortner and directed by Conrad Wiene, which simply never existed.

There is no sense in repeating or quoting the non-stop anti-Semitic slurs, falsehoods, and historical misrepresentations, other than to note that the authors not only vilify the film industry but also the free press in the following chapters: “This is what they looked Like,” and “This was how they kept house.” The tone, much like that of Maga Republicans is one of continual grievance, of being treated unfairly, of a thousand cuts, while harping exclusively on the creation of a threatening enemy from within. However, the final chapter on “The Battle for German Film” does reveal an aspect of National Socialist film policy I have not seen formulated in quite the same way elsewhere, concerning the desire to restructure the German film industry after Hitler’s victory over German democracy. Apparently published in the Spring of 1932, the guidelines formulated most probably by Joseph Goebbels cover production, distribution, reception and censorship.

While the film production section made the usual Nazi demands regarding the removal of Jewish influence, it also called for lowered production costs, subsidies for “German” films, and the creation of one film guild to replace numerous industry trade organizations. The film distribution section reveals the Nazi Party’s anti-capitalist base, arguing for an end to blind and block booking, while licensing and film rentals were to be based on the size and strength of individual theaters, and permitting of new cinemas according to population density. In the technology section, the demand is for the elimination of equipment licenses and the lowering of prices for replacement parts. The film press and censorship were likewise to be controlled at the national level by “volkisch” elements.

All these measures were to privilege small-time, independent theater owners, like Carl Neumann, himself but the result after January 1933 was a gradual nationalization of all aspects of the industry, steered by the master propagandist, Goebbels.