Archival Spaces 351

Film/Whitney Biennial

Uploaded 12 July 2024

I last viewed the Whitney Biennial more than ten years ago, when the Whitney Museum was still located in the Breuer Building on Madison Ave.. However, in 2017 I reviewed the Whitney exhibition, Dreamlands: Immersive Cinema and Art, 1905–2016(Archival Spaces 200 https://www.cinema.ucla.edu/blogs/archival-spaces/2016/11/25/dreamlands-immersive-cinema), the museum now located in the former meatpacking district on the lower Westside. Now in its 81st iteration, the Whiney Biennial “showcases the most relevant art and ideas of our time.” It has often been the center of intense political controversy for its sexism (1987), lack of diversity (1991, 2014), and its connections to arms manufacturers (2019). Organized by curators Chrissie Illes, Meg Onli, Min Sun Jeon, and Beatriz Cifuentes, this year’s Biennial offered both abstract and highly political art by mostly artists of color and also included numerous film/video installations. According to a wall text, “The Biennial is a gathering of artists who explore the permeability of the relationships between mind and body, the fluidity of identity, and the growing precariousness of the natural and constructed worlds.” Interestingly, many of the film/video installations featured works of feature-length, presenting a challenge to visitors unable to spend a whole day in the show.

Diane Severin Nguyen’s In Her Time (Iris’s Version, 2023-24), is a 67-minute meditation on the Japanese massacre of Chinese civilians in Nanjing in 1927, recreating historical scenes, intercut with abstract footage and fan fiction, as well as footage of film extras at the giant Hengdian World Studios, near Jinhua, China. The scenes of the massacre make no attempt at realism but rather feature the artist’s camera roaming around a static tableau of bloodied civilians. Further distancing the viewer from the historical reality of 1937, an actress comments on the making of the work with her own iPhone footage.

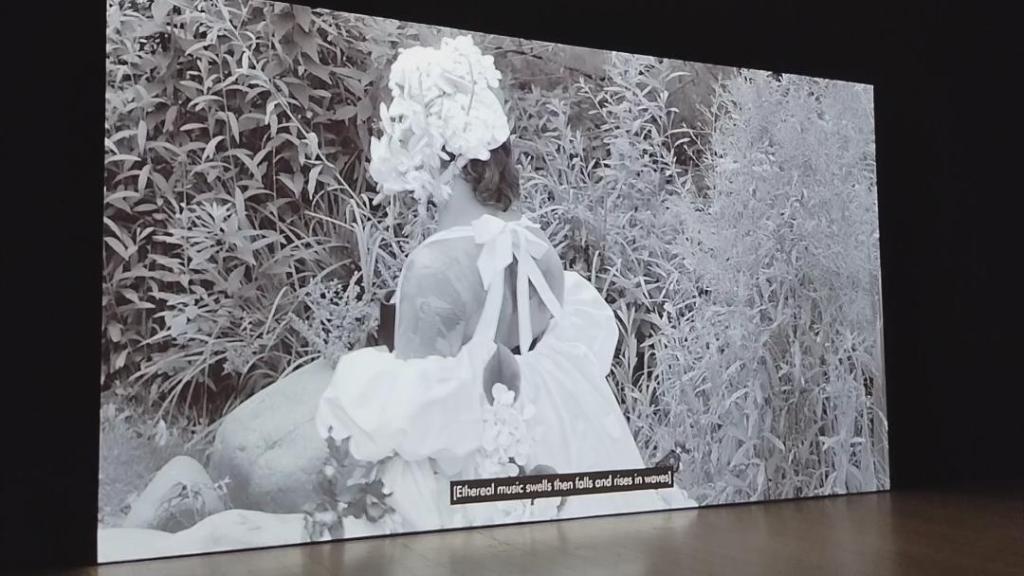

With Pollinator (2022), African-American artist, Tourmaline (formerly known as Reina Gossett), memorializes the Black trans activist and performance artist, Marsha P. Johnson (1945-2022).In the five-minute video, the artist in a white floral dress and elaborate headdress, walks through a garden (B&W), throws flowers into the river (color), and intercuts footage of Johnson’s funeral procession, while her late father, George Gossett, sings “The Cisco Kid” to the artist behind the camera, thereby reminding audiences of the profound legacy of Johnson for the LBGTQIA community.

In Antes de que los volcanes canten/Before the Volcanoes sing (2022), Clarissa Tossin’s 64-minute 4K video, the artist explores the archaeological remnants of Mayan civilization in Guatamala and classical Mayan hieroglyphs in stark white-on black, as well as the appropriation of Mayan architecture by western civilization in Frank Lloyd Wright’s John Snowden House in Los Angeles. The work also presents soundscapes and music (utilizing replicas of pre-Columbian wind instruments), poems, and songs by Rosa Chávez, Tohil Fidel Brito Bernal, and Alethia Lozano Birrueta. The 4K images of nature give the footage a hyperreal feeling, conveying an intense sense of oneness with nature, a unity broken by modern civilization.

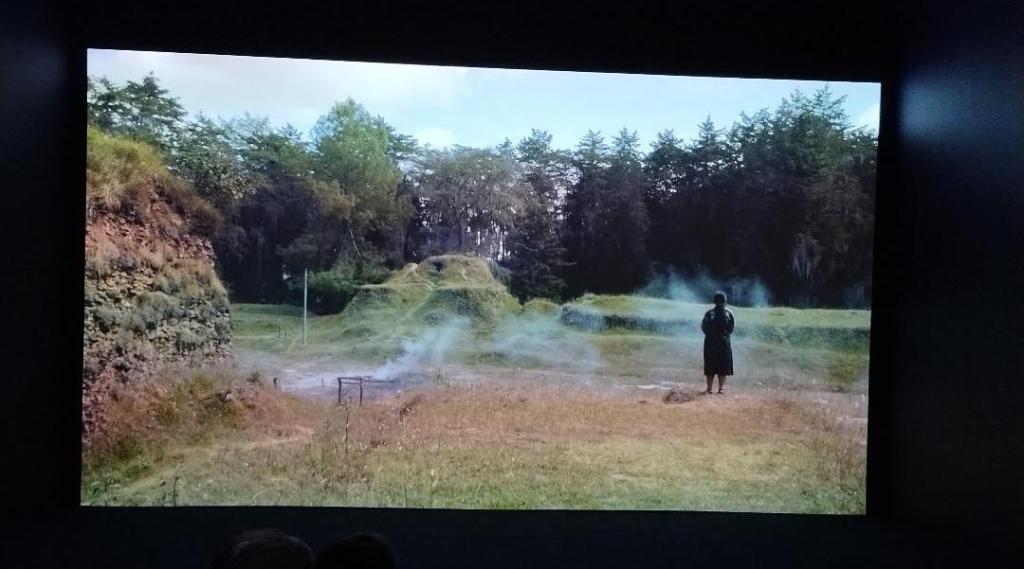

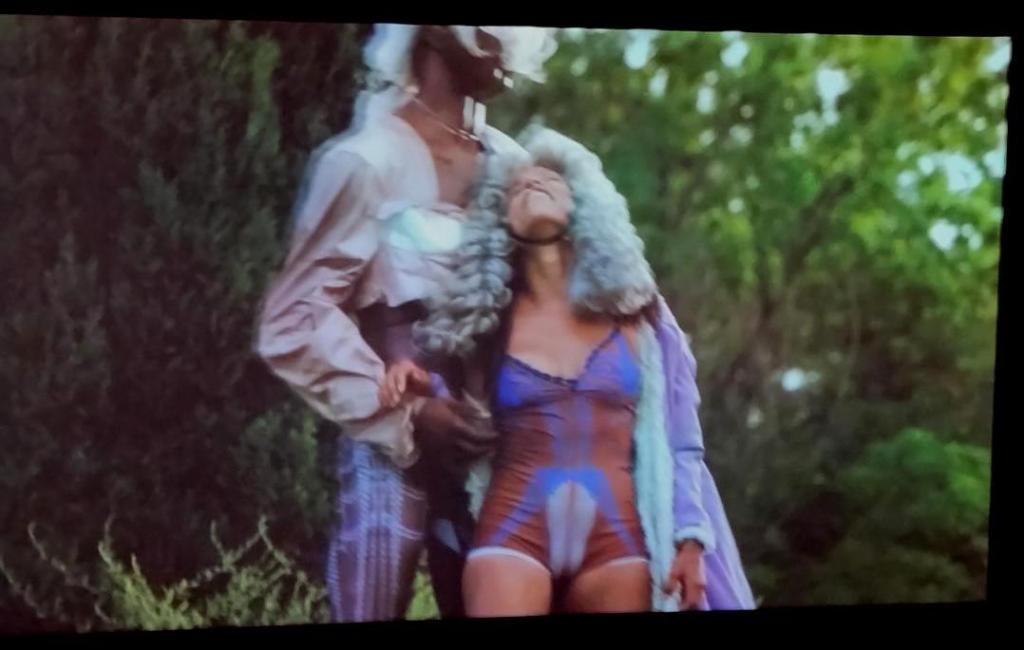

San Domingo-born artist Ligia Lewis based her 20-minute video, A Plot, A Scandal (2022) on her own dance performance piece of the same name. Filmed among the ordered rows of Rimini’s cypress trees (Italy), the artist recites 18th-century laws governing the keeping and maintenance of slaves as property, noting that even children born to slave-freeman couples were considered slaves. The landscape becomes a metaphor for civilization’s attempt to bend nature to its will. Dressing her dancers in historical costumes, while weaving together political and mythical narratives, Lewis catalogues the historical crimes of European white civilization against non-white peoples, as well as the continued dispossession of “Europe’s Others.”

The most interesting installation is Isaac Julien’s 31-minute, multi-screen piece, Once Again… (Statues Never Die), commissioned by the Barnes Foundation in 2022. Coincidently, it can be seen as a pendant to Julien’s Lessons of the Hour (2019), presently viewable uptown at the Museum of Modern Art. While the MOMA show deconstructs the history of American racism in images and texts of the abolitionist Frederick Douglass, the later installation analyses traditional art history’s racist presuppositions about what it has termed “primitive” African art. The British documentary filmmaker is, of course, most well known for his feature films, Looking for Langston (1989), Young Soul Rebels (1991), and Baadasssss Cinema (2002), all of which explore Black art and culture.

In Once Again… Julien reflects on the work of Harlem Renaissance philosopher and critic Alain Locke (1885-1954), played by André Holland, who is seen wandering through exhibitions of African art, contrasted to Albert C. Barnes, played by Danny Huston, who appears among the high western art of the Barness Collection in Philadelphia. Decrying art history’s pejorative labels, Locke advocated embracing African art, to reclaim a Black cultural heritage. Making the connection to modern African-American art, Julien also intercuts modern sculptures by Richmond Barthé (played by Devon Terrell) and Angelo Harrison. Visually, Julien juxtaposes the architecture of the respective exhibitions, again revealing cultural bias: African art is treated as an object of folklore for anthropology in display cases, thus denying it any status as art, while of course western art is valorized as “the true and beautiful.” The work ends with singer Alice Smith, walking down the steps of the Barnes Foundation, celebrating Black art through the blues.

Given Kiyan Williams sculpture near the entrance to the exhibition, this Witney Biennial explicitly pushes back against white nationalist Republican Party efforts to outlaw diversity, sexual and gender equality, and inclusion.