Archival Spaces 393:

The Reception of Cinema Novo in America

Uploaded 20 February 2026

A year ago, on 14 February 2025, Carlos Diegues, one of the best-known directors of the Cinema Novo movement, died in Rio de Janeiro at the age of eighty-four. The young Brazilian film directors who, in the early 1960s, joined together to resist neo-colonialist domination of their national cinema by Hollywood can be considered the first “Third World” cinema to become a part of the canon of cinema history.

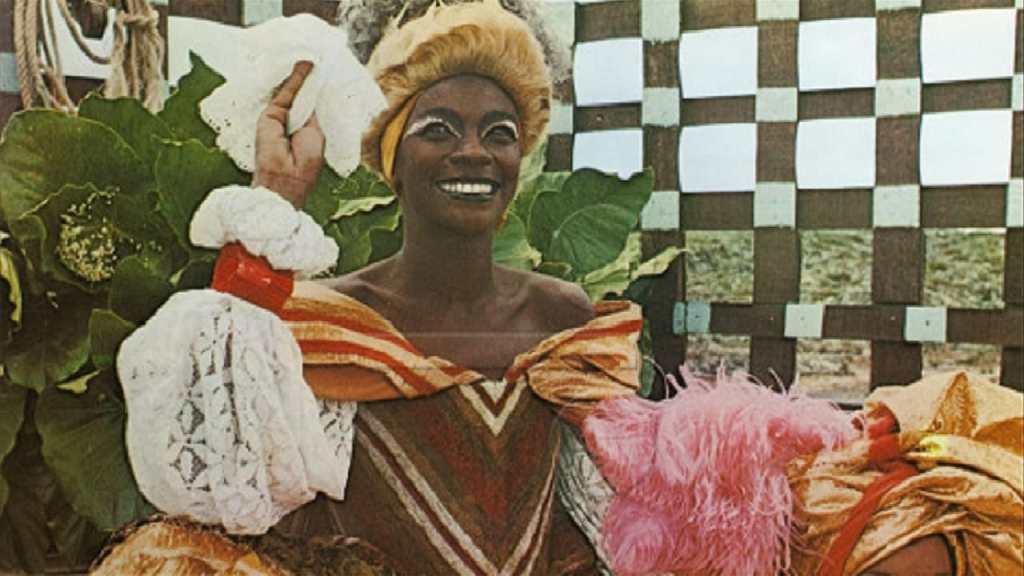

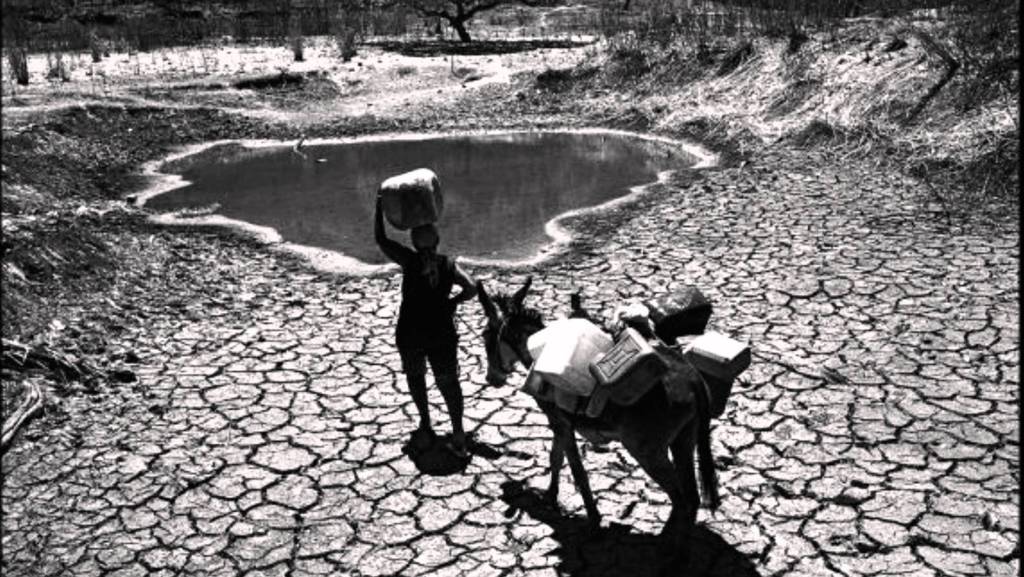

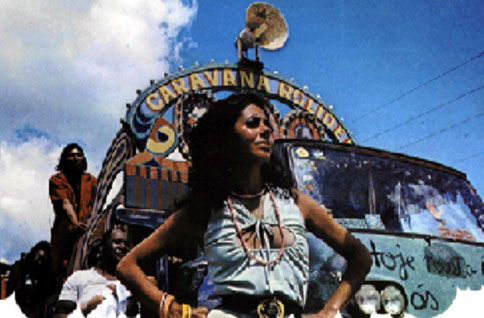

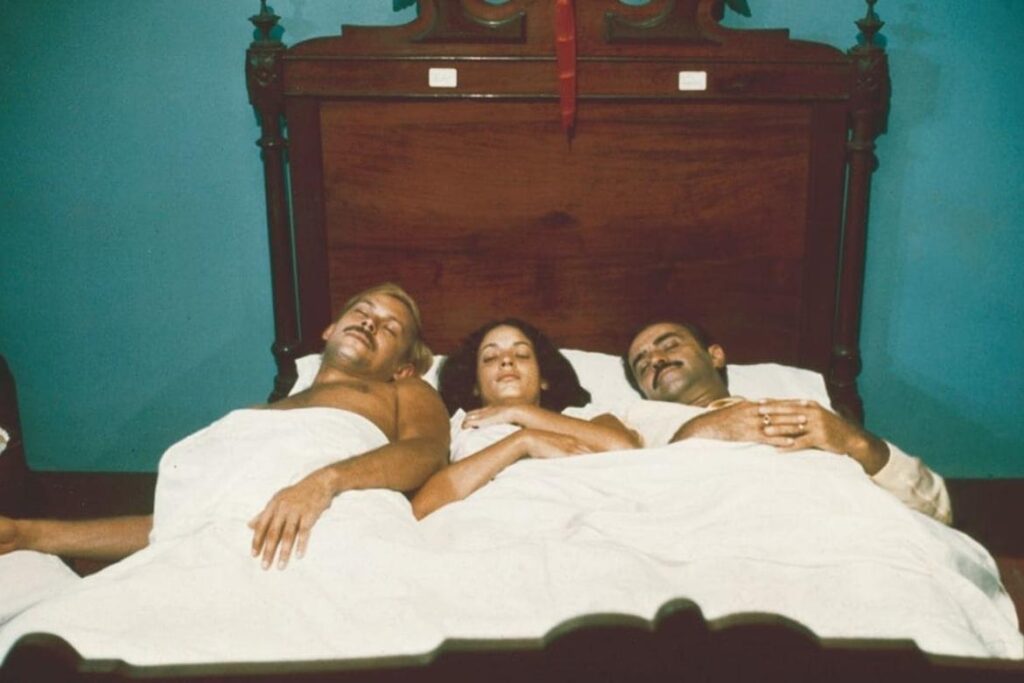

A popular world film history that pays homage to the Cinema Novo movement is Douglas Gomery’s History: A Survey (1991), which argues that Cinema Novo’s most productive period lasted less than a decade; it arguably ended in 1968 with the repressive Fifth Institutional Act, after a CIA-backed military coup in 1964. Indeed, Gomery sees Glauber Rocha’s Antonio das Mortes (1969) as the “end of Cinema Novo.” David A. Cook’s A History of Narrative Film (1981/90), on the other hand, discusses the work of Glauber Rocha, Ruy Guerra, Nelson Pereira dos Santos, Carlos Diegues, Paulo Saraceni, Leon Hirszman, and Joaquim Pedro de Andrade. Cook breaks down Cinema Novo into three distinct phases: “radical optimism and proletarian revolt”(1960-64), “reassessment and disillusion” (1964-68), and “symbolism and mythological allegory” (1968-72). Ironically, the founding of Embrafilm, a company controlled by the Ministry of Culture, eventually led to the worldwide success of Brazilian cinema in the 1970s, involving many Cinema Novo filmmakers, including Diegues’s Xica de Silva (1976) and Bye Bye Brazil (1979), extremely expensive films, mixing magic realism with extravagant visual style, highlighting racial minorities on the margins of society.

The first Brazilian Cinema Novo films reached the United States in the early 1970s, when the core left-wing movement was already a fact of history, some of its directors having gone into exile, like Glauber Rocha and Ruy Guerra. Thus, the reception of Cinema Novo in the United States has always been historical, always a matter for academics and art cinemas in New York, rather than an intended popular cinema. The reasons for the neglect include the initial unwillingness of American film distributors/exhibitors to open themselves to foreign, but especially Third World cinema. It was not until the early 1980s that certain Cinema Novo directors and their Brazilian successors achieved popular commercial success in the United States with films such as Diegues’ Xica, Bye Bye Brazil, Bruno Barreto’s Dona Flora and Her Two Husbands (1978), and Hector Babenco’s Pixote (1980). This late popularity abroad certainly paralleled developments in Brazil, where Cinema Novo had mostly been rejected by the public.

Why did the American reception of Cinema Novo take so long? Throughout the 1960s, Variety’s film critics had been sending back reports to America from film festivals in Venice, Cannes, and Berlin of a new Brazilian cinema. Variety‘s first review of a Cinema Novo film had appeared as early as July 1962 when their film critic, Gene Moskowitz, noted with astonishment that Rocha’s Barravento (1962) been made by a “20-year-old boy.” Even more astonishingly, Guerra’s Os Cafajestes (1962) had won the Grand Prix in Cannes. Over the next eight years, Variety reviewed no less than twenty Cinema Novo films, many of which were winning prizes at festivals. While the critics were skeptical of the commercial chances for these films, many of the reviewers were impressed with their originality and thought the films might find a place in the art cinema market. Typical is the review for Hirszman’s The Deceased in September 1965: “It is technically good and is an off-beater… but it’s worth special handling and personal placement for possible returns via buff (cinephile) audiences.”

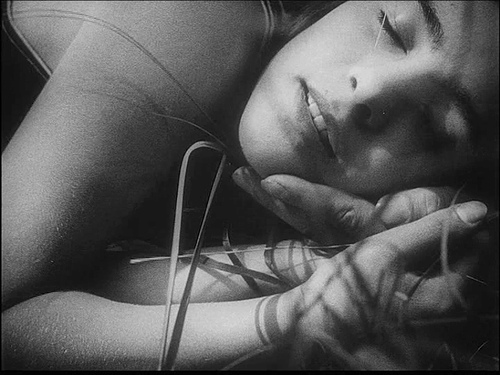

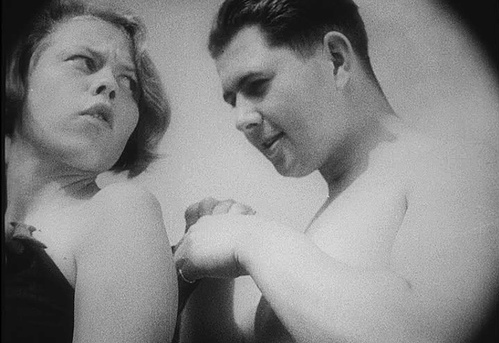

However, not a single Brazilian film was distributed commercially in the United States until June 1969, when Pereira dos Santos’ Vidas Secas opened at the New Yorker Theater. Previously, Cinema Novo had only been screened at the New York Film Festival in 1967 and during a one-week program at the Museum of Modern Art in October 1968. In April 1970, then, Antonio das Mortes opened in New York, distributed through an independent distributor, Grove Press International, followed by Rocha’s Terra em Transe (1967). Several weeks earlier, Frederic Tuten had published the first popular account of Cinema Novo in Vogue and The New York Times, “A Far Cry From Carmen Miranda,” which simultaneously proclaimed the end of the movement, while praising de Andrade’s Macunaima (1969) as the best Brazilian film to date.

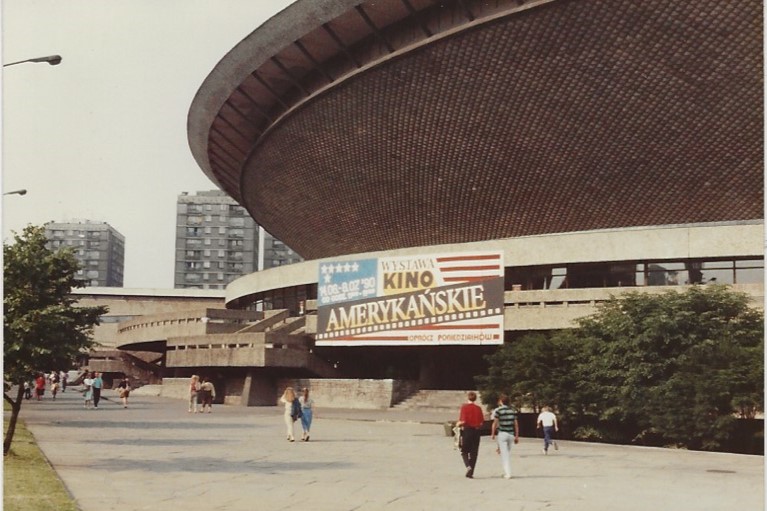

Given this situation, it is not surprising that Cinema Novo films were soon being booked at commercial cinemas in New York as retrospective packages, e.g., at the 5th Avenue Cinema in September and October 1971, when numerous films were introduced to the American public. Distributors, catering mostly to the 16mm academic film market, began distributing Cinema Novo to cinematheques, museums, and colleges, e.g., New Yorker Films, which picked up over twenty Brazilian films from the 1970s and 1980s. Another important step in the wider dissemination of Brazilian films in the United States was Embrafilm’s hiring of an American representative in New York, Fabiano Canosa, who worked with the distributor, Unifilm, to look after Brazilian film interests.

Despite this increased activity in the theatrical and non-commercial film market, it was to be another several years before the reception of Brazilian cinema would be reflected in serious film journals. For example, a sympathetic, critical introduction to Cinema Novo appeared in the left-wing journal, Jump Cut, Nos. 21 (1979) and 22 (1980), in which Randall Johnson and Robert Stam presented two special sections, “Brazil Renaissance: Beyond Cinema Novo.” Their argument for the delayed reception of Cinema Novo in the United States was: “While Hollywood dumps its waste products on Brazil, the Brazilian film industry, although the third largest producer of feature films in the`West,’ has difficulty getting its best products even seen on its own multi-national-dominated TV screens, not to mention non-Brazilian screens.”

In the 1980s, then, Randall Johnson published no less than three English-language books on Brazilian cinema: Brazilian Cinema (1982, co-edited with Robert Stam), Cinema Novo x 5 (1984), and The Film Industry in Brazil (1987). All three books historicized Cinema Novo in the context of the Brazilian film industry as a whole, arguing that the movement must be seen in the long term as the beginning of modern Brazilian cinema, rather than as an isolated phenomenon.