Archival Spaces 384:

Remembering Bundesarchiv President Friedrich P. Kahlenberg

Uploaded 17 October 2025

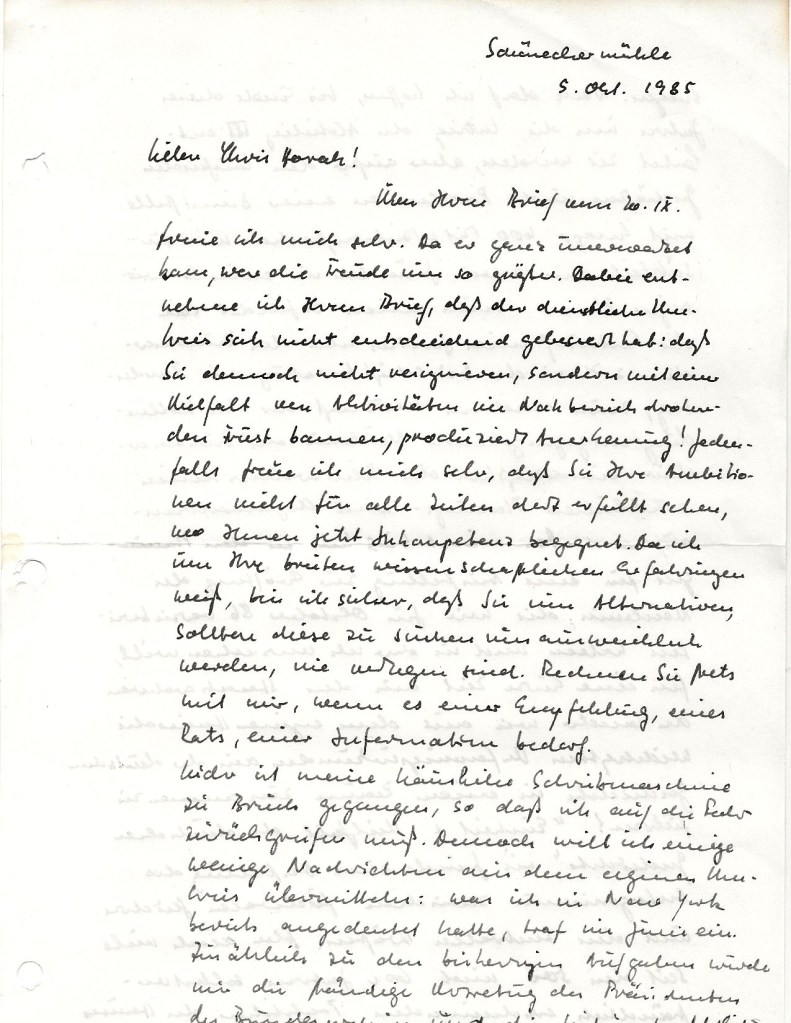

Prof. Dr. Friedrich P. Kahlenberg would have celebrated his 90th birthday in twelve days. Born on 29 October 1935 in Mainz, where the Main and Rhine Rivers run together, Kahlenberg was one of my most important mentors, the person responsible more than any other for my film history and archive career on two continents. I only realized that fact when I recently looked over the more than 40+ letters we exchanged between 1976 and 1985, a period when I was trying to find my place in the film archive world, while also completing a PhD. His official letters were typed (no computers yet), but his more personal letters were hand-written in a beautiful cursive, the longest of which was six pages, sent from his country house in Schönecker Mühle, a hamlet in the northern corner of the Hunsrück Mountains, made famous by Edgar Reitz’s monumental Heimat TV series. We last met face to face in the late 1990s in Munich, when I had become Director of the Munich Filmmuseum and he was President of the Federal German Archives; at a time he was preoccupied with the legacy of terror, represented by the East German STASI (Secret Police) Archives, which included files on 6.8 million GDR Germans in 69 miles of running documents.

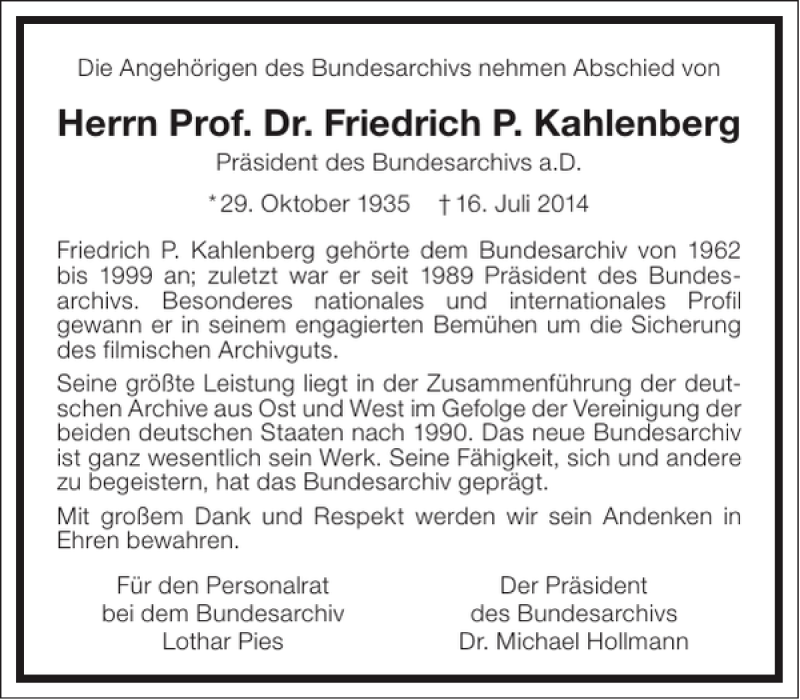

Friedrich P. Kahlenberg completed his PhD. in history in June 1962 at the University of Mainz with a dissertation on the military policies of the Electors of Mainz in the 17th and 18th centuries and immediately thereafter became an intern at the Federal German Archives in Koblenz, finishing his archive studies in March 1964. He entered public service at the Bundesarchiv in Division II (Government documents), becoming its chief in 1965. Four years later, he joined the Bundesarchiv’s administrative unit (Referat II 1), where he was responsible for capital planning. In January 1973, Kahlenberg was named head of Division III (non-paper materials), which included the film archive. That same year, at his behest, the film archive became a member of FIAF (Fédération Internationale des Archives du Film). He guided the fortunes of the film archive for 12 years, expanding its international reputation and making the preservation of Germany’s national film patrimony a priority for the first time in the institution’s history. Transferring to Division I (Central) in 1985, Kahlenberg was appointed President of the Bundesarchiv in June 1989, a point at which it was not yet clear that he would be responsible, beginning in October 1990, for the integration into the Bundesarchiv of the State Archives of the GDR, including the Staatliches Filmarchiv DDR, the giant STASI archives, and later the Berlin Document Center (the Archives of the Third Reich). He retired in November 1999, having achieved the monumental task of creating a functioning archival system for Germany. Meanwhile, Kahlenberg also taught history at the University of Mannheim for more than 25 years. He died in Boppard on the Rhine on 16 July 2014.

Kahlenberg’s first official letter to me is dated 1 Nov. 1976, when he expressed his regret that there were at present no open positions in the Bundesarchiv Filmarchiv, and that film archive positions were extremely scarce throughout Germany. A handwritten letter followed only six weeks later, after I had reported that I was interviewing for a position at the University of Munich. We met in Koblenz the following Summer, at which time I was able to tour the film archive, while we discussed my applying for various PhD. programs. Days later, Kahlenberg wrote letters of recommendation to the Professors Knilli (Berlin), Reimers (Munich), and Lerg (Münster), also procuring for me an invitation to the founding conference of the International Association of Audio-Visual Media and History (IAMHIST), which Reimers was hosting in September 1977, and which Kahlenberg also attended. Those letters resulted not only in my acceptance as a doctoral candidate with Prof. Winfried B. Lerg but also in a close association with IAMHIST after presenting a paper there. Several more letters followed in Autumn 1977, including a note that Kahlenberg had discussed my PhD. proposal for a history of German-Jewish film exiles in Hollywood with Karsten Witte, the well-known critic and Kracauer editor, who would later become a friend, giving me indirect international recognition when he reviewed the 1981 Venice Biennale conference, “Berlin-Vienna-Hollywood.” Kahlenberg’s academic interests were many, but the history of the Third Reich and the fate of German exiles interested him in particular.

Meanwhile, in March 1978, just as I was moving to Münster, Kahlenberg recommended me to the editor of Der Archivar, a quarterly journal of all German archives, where I then published an article on the state of American film archives; my first in German. Several more letters followed in which Kahlenberg discussed the feasibility of my applying for a lower-level position in the film archive, a position which, to his regret, he was forced to fill internally with a non-film specialist. Finally, in Spring 1979, an Assistant’s position opened up, but Kahlenberg expressed his regrets after I applied that I was ineligible because I was an American citizen; he had assumed I was German. The position went to Karl Griep, who became a friend.

In 1980-81, Kahlenberg recommended me to two film production companies as a film researcher: Bernhard Frankfurter’s Austrian TV film, On the Road to Hollywood (1982), allowed me to travel to New York for my film exile research, as well as do contract work. and Edgar Reitz’s prize-winning television series, Heimat (1984); I visited the set and conducted research at the Bundesarchiv for documentary clips inserted into the film. I also visited him in Koblenz in May 1980, where we discussed the outline of my dissertation, a proposal my thesis advisor had already seen in March.

In 1982-83, our correspondence intensified again, because I had discovered in the course of my curation of an exhibit on the German-Jewish photographer filmmaker Helmar Lerski what I thought was a lost film. Avodah/Work had turned up in a laboratory in Budapest, so I asked Kahlenberg to request the material and preserve the film, which he gladly did. Unfortunately, the material turned out to be merely outtakes, and it would take another ten years for a print to be discovered in London. Other letters concerned bibliographic and research suggestions for my dissertation, which I was able to report had finally been completed in December 1983.

As noted in a letter in December 1984, Kahlenberg was extremely happy that I had landed a job as Associate Curator at George Eastman Museum, announcing in the same letter that he had been asked to move out of the film archive into the Federal Archives directorate. His subsequent personal letters were filled with the many problems he was encountering in managing an unwieldy bureaucracy, and understandably became ever less frequent, although we heard about each other through Karl Griep, who had become Kahlenberg’s successor. Given his exalted position in the Federal German Archives, I’m still surprised and unbelievably grateful that he took a young American student under his wing.

Chris, I have never read anything from you that is not utterly illuminating. What a wonderful tribute.

Best,

Scott

LikeLike

Thank you so much for your kind words.

LikeLike