Archival Spaces 383:

Four German Comedies (1931-32) Blu-Ray

Uploaded 3 October 2025

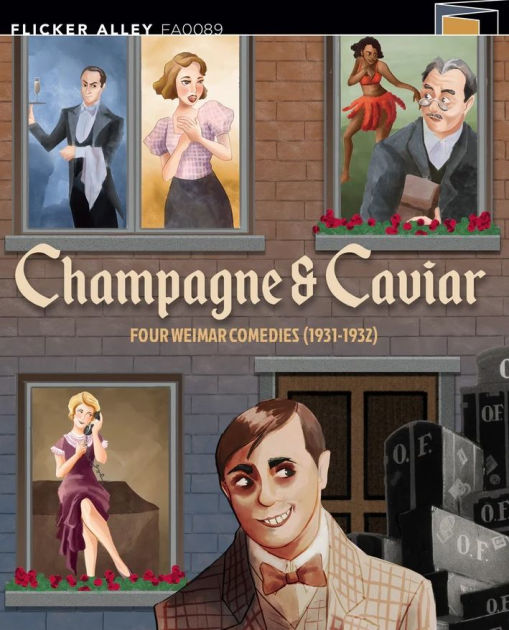

Flicker Alley has released a two-disc blu-ray set, “Champagne & Caviar: Four Weimar Comedies (1931-1932),” which for all the many merits of the presentation, is somewhat of a misnomer. Produced during the depths of the world-wide Depression, these are not frothy Hollywood comedies in the style of Ernst Lubitsch, taking place in the upper classes of New York or Ruritania, but rather are focused on the impoverished and mostly desperate German middle and working classes, attempting merely to survive through their wit, graft or chutzpah, while Hitler’s fascist regime is clearly visible on the horizon.

The opening salvo is fired by Wilhelm Thiele whose comedy, The Private Secretary (1931), stars Renate Müller (Vilma) as an unabashed gold digger, hoping to marry wealthy. She turns down an offer to sleep with a mere employee, telling him she doesn’t want to stay in the typing pool forever, then latches unwittingly onto the firm’s director (Hermann Thimig), who says of her after she refuses to become his mistress: “A crafty character who knows exactly what she wants.” Helping her reach her goal is the delightful Hasel – translates as Bunny – (Felix Bressart), whose singing and dancing to Thiele’s leitmotifs provide comedy relief, and who convinces the reluctant Villma to marry with the line: “Think of the Happy End.” That self-reflexive conclusion is buttressed by multiple exposures in close-up of pining young women in Vilma’s boarding house, representing the film’s female audience. “The little shop girls,” as siegfried Kracauer called them in a late 1920s essay. The film was simultaneously shot in a French version and proved so popular that it was immediately remade in Britain and Italy.

Ludwig Berger’s I by Day and You by Night (1932) not only visualizes the plight of the working poor but also consciously parodies Hollywood’s operatic fluff. Grete (Kathy von Nagy) is a manicurist and Walter (Willy Fritsch) a waiter, who unbeknownst to the other share a bed, one by day, the other by night, but have never crossed paths. They meet on town and fall in love, both claiming to be wealthy, while hiding their working-class origins and their occupations as wage slaves. Berger frames their story with scenes in a movie theatre, inserting an on-screen film operetta produced by the Bombast Film Co. – the singer Ursula van Diem looks just like Lubitsch’s Jeanette MacDonald – introduced and commented in a heavy Berlin dialect by the working-class film projectionist. The film-within-a-film scenes are preceded by fireworks, again creating a self-reflexive moment, while the working-class love story outside the cinema is contrasted with the unrealistic narrative among the upper crust on screen.

The petit bourgeoisie and their philistine morality are the subject of Frtiz Kortner’s The Upright Sinner, a biting comedy written by Vienna’s premier satirist, Alfred Polgar. “Head cashier Pichler” – the Austrian mania for job titles lives here – played by Max Pallenberg in his only sound film role, doesn’t want his daughter to work, even though he can barely support his family. Pichler and Wittek, the latter sweet on Pichler’s daughter (Dolly Haas), are sent to Vienna with 6,000 Schilling to give to the company’s CEO. They lose the money in a night of drunken revelry and are seduced by an African American jazz singer, but fate comes to their rescue when the CEO absconds with even more of the company’s money. Pallenberg plays the bumbling fool, misunderstanding and misspeaking his way through the proceedings, while Heinz Rühmann as Wittek embodies “the little man” character he would make his own in dozens of subsequent Nazi German films. Kortner enlivens the story with many expressionist techniques, including introducing animal sounds for human characters and creating a drunken dream sequence in which angels and locomotives are transformed into monstrous projections of the ego. After worrying that he will go to prison, Pichler complains when he is only made a temporary company director. Kortner, who would be forced into exile by the Nazis and was vilified in the Nazi-infested Federal Republic af his return, delivers his poison-pen letter to the German middle class here, fully aware of their racism and mendacity, which will result in Hitler’s fascism.

Like Alexei Granowsky’s previous film, The Song of Life (1930), an avant-garde musical with only a bare semblance of narrative, The Trunks of Mr. O.F. (1931) is a musical comedy, structured as an endless cabaret show, visualizing an economic boom that transforms a sleepy country village into a bustling metropolis, an illusion of promise during the depths of the Depression. According to the opening song, it is a “fairy tale” for adults, with much of what follows tongue-in-cheek. Thirteen suitcases arrive in a rural village where pigs still roam freely in the square and the hamlet’s motto is: “Better two steps backward than one forward in haste.” The mysterious suitcases unleash a tidal wave of speculation about their absent billionaire owner, leading to massive modernization, unbridled financial investment, and rapid urbanization, as the town’s mayor (Alfred Abel), a journalist (Peter Lorre), and an architect (Harald Paulsen) keep the rumors flying that the owner will invest millions. Granowsky cleverly intercuts footage of huge building projects and stock market mania with musical nightclub numbers, fashion shows, and the rising wealth of the townspeople. A world economic conference also meets in the new Ostend, but after more than a 1000 sessions, is unable to discover the origin of Ostend’s boom; meanwhile, no one even remembers the 13 suitcases that started it all. Near the end, we learn, the baggage was actually destined for Ostende, the wealthy Belgian seaside resort, not the “dark spot” on the map called Ostend.

What sets all of these comedies/musicals apart from American films is the way they disrupt viewer identification, incorporating patently unrealistic and dream sequences which satirically comment on comedic narratives involving the mostly petit bourgeois pretensions of their protagonists. One of the joys of these films, is seeing a number of German actors who in exile would have prominent careers in Hollywood in mostly character parts, including Hedy Lamarr (Algiers, 1938), Peter Lorre (The Maltese Falcon, 1941), Dolly Haas (I Confess, 1953), Felix Bressart (To Be or Not to Be, 1942), and Ludwig Stossel (The Pride of the Yankees, 1942). All four films feature audio commentaries by well-known German film scholars, as well as a beautifully produced souvenir booklet.

I’m ordering it!

Joe Lauro Historic Films Archive 211 Third Street Greenport NY 11944 p.631.477.9700 | t.800.249.1940 historicfilms.com http://www.historicfilms.com/

LikeLike

Hi Chris,

I particularly enjoyed this column as it provided a “review” of each of the films you discussed…and I liked that you pointed out the weakness of how the films were positioned as “comedies,” as we think of the term.

-marty

Marty Cooper

President

Cooper Communications

16000 Ventura Blvd.

Suite 1000

Encino, CA 91436

Direct: 818-359-0231

LikeLike