375: My career as an Art Smuggler

Archival Spaces 375

Uploaded 13 June 2025

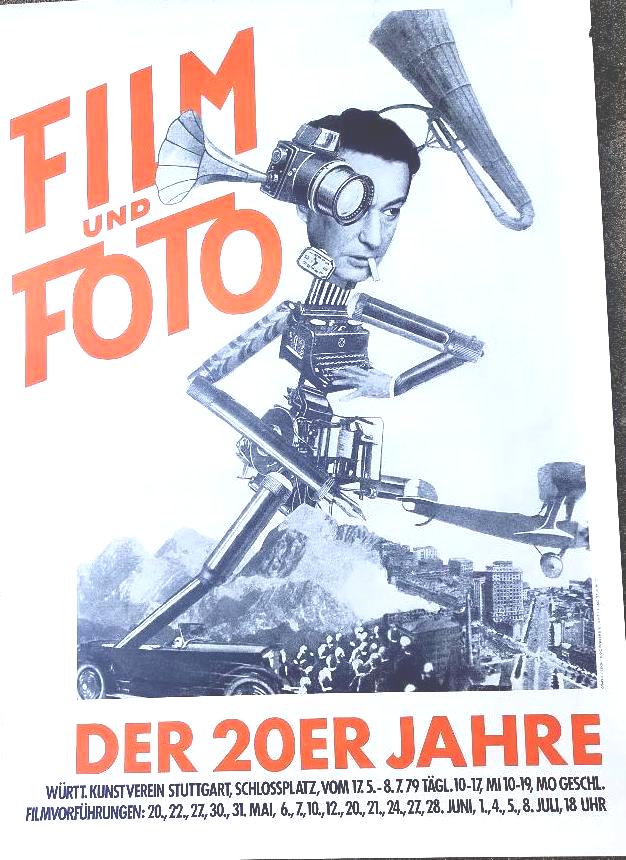

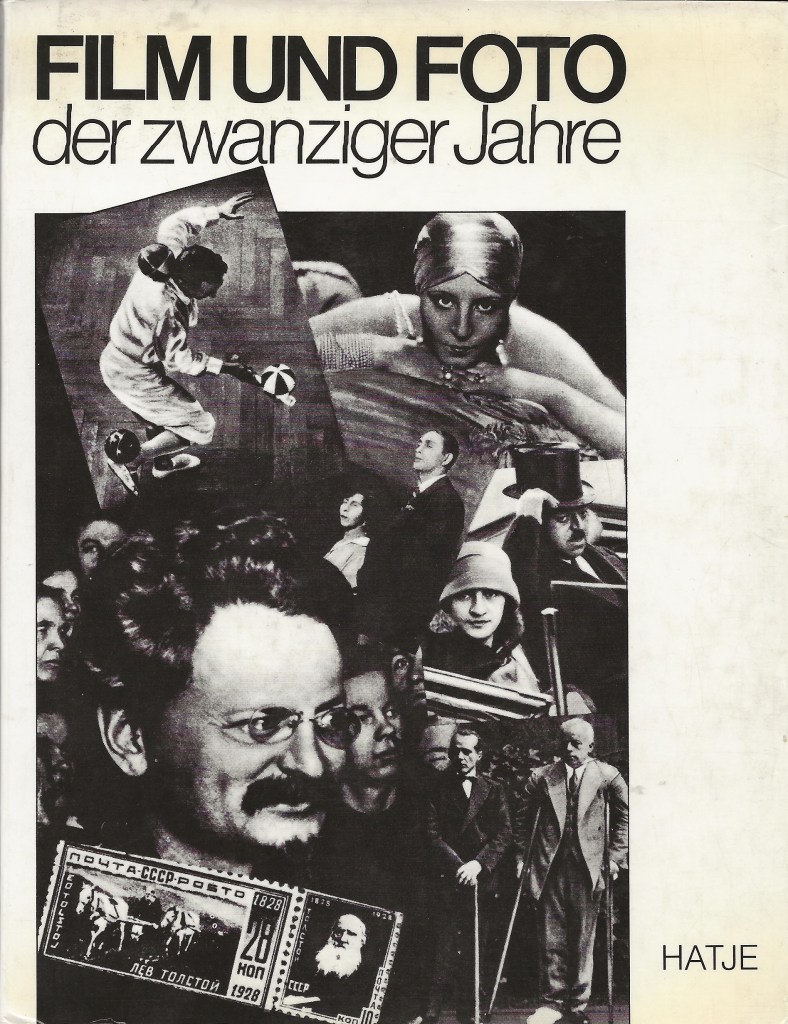

In Spring 1979 I was working as a free-lance curator on the exhibition, “Film und Foto der zwanziger Jahre/Film and Photo in the 1920s,” for the Würtembergischer Kunstverein in Stuttgart, Germany. At the time I was a year into my PhD. studies at Münster University, still living in a dormitory. I had gotten a call in September 1978 from a colleague, Ute Esklidsen, who I had met at George Eastman Museum in Rochester when we were both post-graduate interns, she a year after me. She had been hired by Tilman Osterwold, the director of the Kunstverein to curate the photography show and she asked me, if I would handle the film section. The exhibition was in fact a reconstruction of “Film und Foto,” which had been staged in Stuttgart exactly 50 years earlier in May 1929 by Laszlo Moholy-Nagy and Hans Richter, both hired by the German Werkbund; it brought together all the various avant-garde movements in Europe and America, as they pertained to the then new media of film and photography. Richter’s film program included everything from features, like Vertov’s Man with the Movie Camera (1929), Marc Allégret’s Voyage au Congo (1927), Pabst’s Secrets of the Soul (1926) and Dreyer’s Passion of Joan of Arc (1928), to avant-garde shorts, like Richter’s Inflation (1928), Ivens’ Rain (1929), Duchamp’s Anemic Cinema (1927), and Mol’s Life in Water Drops (1928).

I had my first planning meeting with Ute in Fall 1978 in Essen, an hour South of Münster, where she was living and would soon become the photography curator at the Folkwang Museum. I immediately began working on and off researching the exhibition, particularly the 1929 film program, its participants, and also locating modern sources, where the surviving films could be accessed for our program, which was scheduled to open on May 16, 1979. In the early months of 1979, I made several research trips to Paris, Frankfurt, and Stuttgart, then began writing my catalogue essay, while Ute worked on the photography and graphic design section that included examples of German New Realism, Soviet Constructivism, French Surrealism, Dutch de Stijl, American Straight and advertising Photography, and Czech Devětsil

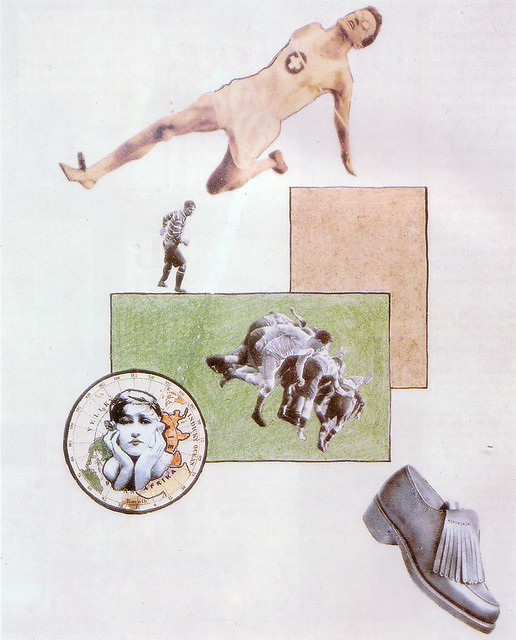

It was in connection with the last-named art movement that Ute asked me to meet some people in Prague, where I was heading for Easter to see my Babi and Aunt Liba, and bring back some images for the exhibition. My girlfriend and I boarded a student bus to Prague in Kassel on 11 April, crossing the border to Communist Czechoslovakia in the early afternoon. Shortly behind the border, a gentleman got in and exchanged money for us into Czech Crowns at an exchange far better than the official government rate – I later learned this was sanctioned by the Státní bezpečnost (State Security). The next day, I met Mr. Venera below the King Wenceslas statue on Václavské náměstí, where he handed my three photo montages in a brown bag. I wrote in my diary:

“He was almost my height, gray hair, good-looking, badly made Czech clothing. I told him how I planned to smuggle them out of the country. His face immediately clouded over. He said if there was trouble, he couldn’t afford to have his name connected with these historical works of art. He told me that if they asked about them on the border, I should just say my father had made them in his youth and give them up without a fuss. He then quickly said he had to leave for Brno, because his son was ill. I gave him a bag with several jazz records Ute had told me to bring from Germany. He thanked me profusely, and then he was gone, disappearing into the crowd. I was suddenly in a total daze and incredibly moved by the experience, maybe because so much had been expressed, but left unsaid. I also felt really good, because I had done something concrete for someone, and suddenly felt more connected to my roots than I had ever been, maybe because my illegal work brought me closer to my father and his resistance work in 1948.” (See https://www.cinema.ucla.edu/blogs/archival-spaces/2018/08/31/abduction-petr-zenkl)

I next visited Emilia Medekova, the widow of the famous Czech painter, Mikuláš Medek. I gave her money for the art historian Anna Farova, who had written a piece for our Film and Foto catalogue. I couldn’t meet Anna directly, because she was under heavy police surveillance, due to her signing Carta 77, which called for the Czechoslovak government to abide by its own human rights documents; she was also banned from working. Medekova and I only spoke briefly, but I felt the oppressive atmosphere under which her late husband and all Czech artists and writers suffered, with every inch of wall space covered with paintings that had never been seen in public.

Our journey out of the country turned out to be uneventful. No customs officials felt it necessary to search a bus full of poor German students. The Markalous images were exhibited for the first time in our exhibition and are now a part of the Folkwang Museum Collections.

Postscript: In November 1986, I was nearly arrested at the Czech border for attempting to smuggle “pornography” into the country. In fact, I was a legitimate courier, carrying Muybridge “Animal Locomotion” images from George Eastman Museum, to be exchanged for E.-J. Marey photographs from the Technical Museum in Prague, and I had a letter to prove it.

Dear Chris, thank you! Interesting as usual! Wow, smuggler of pornography! :DD Greetings to Mindy and love to both of you! Lenka Â

LikeLike

Wonderful essay.

Jaroslav

LikeLike

I’m glad to see you can add international art smuggler to your resume as well as a cold war spy(from a previous archive).

LikeLike

Fascinating piece of time and history, Chris. Love the photo from the opening.

LikeLike

Hi, Chris! As always, I enjoyed this post on your brief foray into “art smuggling”, heh. I had a quick question though: Where is that second still in your email from originally? It’s labelled as being from Richter’s “Inflation”, but I don’t believe it’s from that film. I the still I’m referring to is a B&W image of a row of people in a factory-type setting reclining, apparently from exhaustion, against a group of large metallic wheels that are held up by chains. I haven’t been able to discover the source of it, & any help you can give me on that would hugely appreciated!

Roughly, — Dan Jeremy Brooks

President of the Aurora Film Society http://www.projexploitation.com http://www.aurorafilmsociety.org http://www.aurorafilmsociety.org http://www.projexploitation.com http://www.projexploitation.com

LikeLike

Thanks for your comment. Sorry to say, I don’t know. And it might be a misidentification. I thought I’d cribbed it from Google images, but now can’t find it. I might have found it in an image file on my desktop, but since I’m out of town, I can’t check. I’ll look when I’m home this weekend, but assume it is a misidentification if you don’t hear back from me.

LikeLike

Thanks for checking on that for me! I thought at first that it might be one of those Lewis Hine factory snapshots, but I’m still unsure.

LikeLike

Dan,

I double checked my desk top and apparently I downloaded image from net and mislabelled it INFLATION, because I can’t find it anywhere except as a file in my image files. Sorry.

LikeLike

Thanks for checking on that for me! I thought at first that it might be one of those Lewis Hine factory snapshots, but I’m still unsure.

LikeLike

No problem, Chris. Thanks for looking for me! If I ever figure out what its from, I’ll let you know post-haste!

LikeLike