Archival Spaces 330

Flicker Alley’s Foolish Wives (1922)

Uploaded 15 September 2023

I met Arthur Lennig several times in the mid-1970s to late 1980s, mostly at IAMHIST (International Association of Audio-Media and History) Conferences, where he talked about his work on Stroheim and Griffith. He was really quite passionate about his research, that energy resulting in his Stroheim book (Lexington: U. Press Kentucky, 2000). He didn’t have much good to say about MOMA, I remember. Prof. Lennig gets a big credit from James Layton (and all the restorers in the booklet to Flicker Alley’s release of the restored Foolish Wives (1922). In 1972, Lenning attempted an early restoration, working from two different prints.

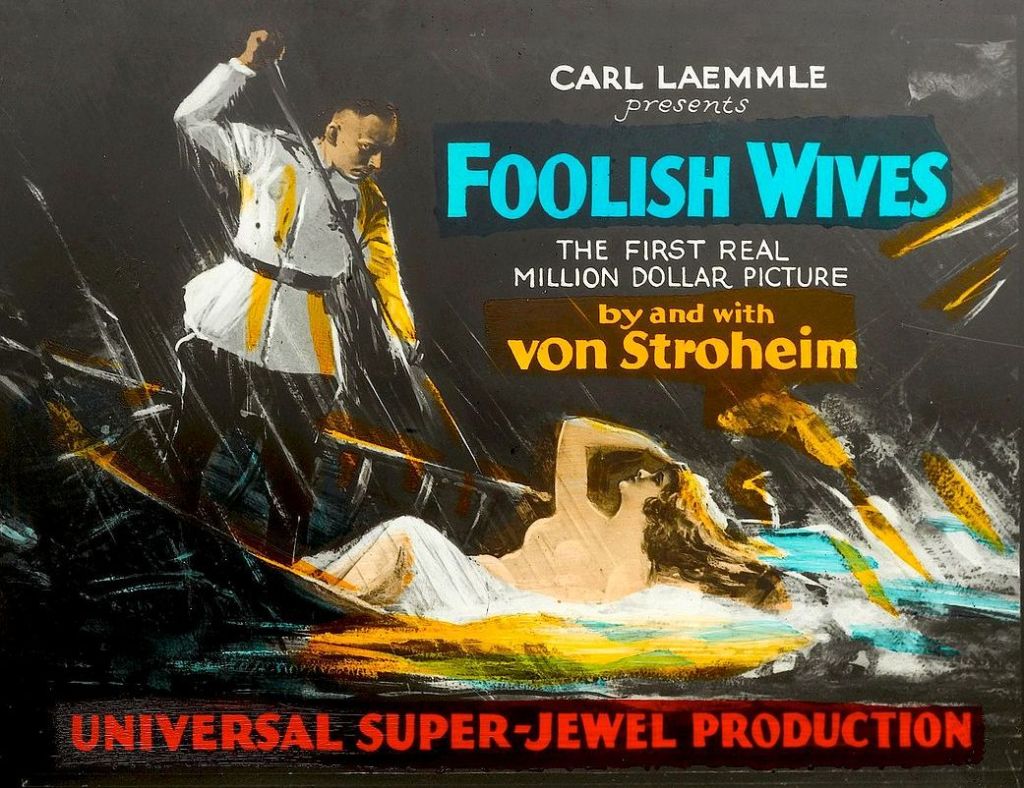

When Erich von Stroheim’s Foolish Wives opened on 11 January 1922 at the Central Theater on Broadway, it had a length of 14 reels (14,120 ft) and was hailed by critics, like Harriet Underwood of the New York Herald Tribune, as another masterpiece by one of America’s greatest directors. It was the first film by Carl Laemmle’s Universal to play Broadway, the studio previously producing mostly low-budget programmers and shorts. Yet, immediately after the premiere, the film was cut down to ten reels (10,620 ft), then even further, due to censorship cuts demanded by State Censorship Boards. Irving Thalberg, Universal’s Boy Wonder had demanded the cuts because the film’s extreme length would not play in the Hinterlands, Universal’s usual market, therefore its astronomical costs could not be amortized. The film played for a year on Broadway but still lost money; von Stroheim’s reputation never recovered; he became known as a manically uncompromising and wasteful director.

However, that was not the end of the carnage; Stroheim’s first cut came in at 30 reels, to be shown in two parts on two consecutive evenings. In 1928, Universal planned to rerelease the film, probably with sound, re-editing it down to a mere eight reels and replacing the titles, then scraping the project. That version, which survived at the Museum of Modern Art, as well as a second Italian source, as Lennig (and Richard Koszarski) discovered, were all audiences had ever seen, until in October 2017, Rob Byrne of the San Francisco Silent Film Festival and Dave Kehr of the Museum of Modern Art decided to attempt a reconstruction which would approximate von Stroheim’s film. They found an Italian release print, which had also originated from the 1928 version, but from the export version negative; crucially it included the film’s climactic fire scenes missing in MOMA’s version. Working with a team that included James Layton, Kathy Rose O’Regan, and Peter Williamson, Byrne and Kehr were able through extended research in print archives to reedit the film closer to Stroheim’s vision, consulting an original shooting script and continuity, and Sigmund Romberg’s piano score, among other documents. Using censorship records they also recreated many of Stroheim’s original titles, while Foolish Wives’s color, consisting of tints, tones and hand-colored scenes was added, based on the Italian print and other hand-colored films by Gustav Brock.

A restoration plan was made for the 1,953 surviving shots and then restored frame by frame in a digital edit, the restoration premiering in 2020 at the San Francisco Silent Film Festival. The restoration team also made the decision to preserve both the film’s grain structure and other surface imperfections to retain the film’s original look. That 147-minute version (9,766 ft) has now been released by Flicker Alley, allowing for the first time a glimpse of what Stroheim’s film had achieved.

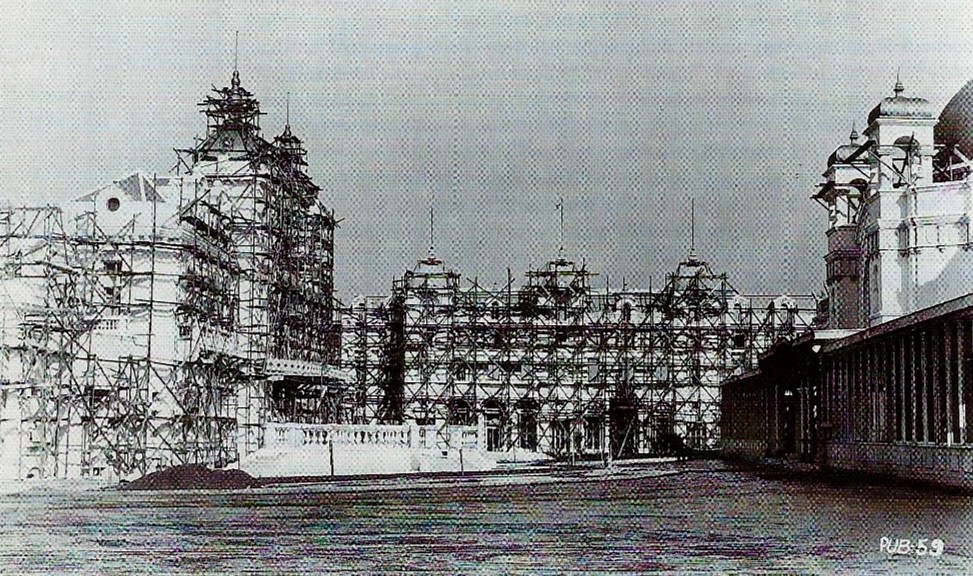

Iris Barry, later founding film curator at MOMA famously wrote in her book Let’s Go to the Pictures (1926) that Stroheim had taught Americans about nuanced acting, the importance of the tiniest gesture in establishing character. He not only directs himself, defining his character with minute changes in physiognomy, but also his costars, in particular Maud George, Mae Bush, Cesare Gravina, and Dale Fuller who would become Stroheim regulars in subsequent films. Indeed, Stroheim’s insistence on realism in the gigantic exact replica sets of Monte Carlo, the costumes, and acting was unlike anything American cinema had previously produced. It had taken 11 months to complete shooting, all the while R.H. Cochrane, Universal’s P.R. man announced the rising dollar costs on a giant billboard on Times Square. Stroheim was still shooting close-ups when Thalberg had the cameras confiscated; moving to Metro, Thalberg would next butcher Stroheim’s magnum opus, Greed (1923).

Shooting his most important scenes first, so the studio could not remove him from the picture, von Stroheim played the lead role of the fake Count Sergius Karamazin, who with his two “cousins,” the Princesses Olga and Vera Petschnikoff, operate a counterfeit money scheme, while cheating at the Casino. It is implied that the thoroughly amoral Count not only sleeps with his cousins, but has impregnated the maid, attempted to rape the feeble-minded daughter of his counterfeiter, and seduced the wife of the American Ambassador. Karamazin can’t help himself, he is obsessed with sex and money, his ever-present monocle and elongated, burning cigarette exuding his supreme arrogance and egoism. Things, of course, all end badly for the crooks, but never had American audiences seen such unapologetic evilness and corruption, given that American films almost never strayed far from the boy meets girl happy ends. The film’s melodrama is however mitigated by the film’s realism, which Stroheim achieved through extreme compositions in depth, masses of extras in crowd scenes, and attention to details everywhere. Indeed, the film’s realism allows von Stroheim to peel away layers and layers of artifice to reveal the sordidness and corruption of a post-World War I society bent on pursuing pleasure for its own sake.

This film is a must-see for anyone only familiar with the mangled 16mm versions previously in circulation or anyone who has never seen a Stroheim film. Flicker Alley’s Blu-ray/DVD is also chocked full of bonus materials, including an original short from 1922 on the making of the film, several new documentaries, before and after comparisons, a photo gallery, and an illustrated souvenir booklet with more information on the film’s fate and restoration.

Hi Chris,

Brings back fond memories of watching in Bologna (2022) the restored version of Foolish Wives with the fire scene in colour. By the way, you may want to correct the names of Arthur Lennig (written in various ways) and Maud George.

I didn’t know Arthur Lennig, so I immediately confonded him with Arthur Lehning ??

Kind regards,

Ivo ________________________________

LikeLike

Thanks for your eagle eyes. I made the corrections.

LikeLike

You’re welcome.

LikeLike