Archival Spaces 329

Tales from the Vaults: Film Technology over the Years and across Continents

Uploaded 1 September 2023

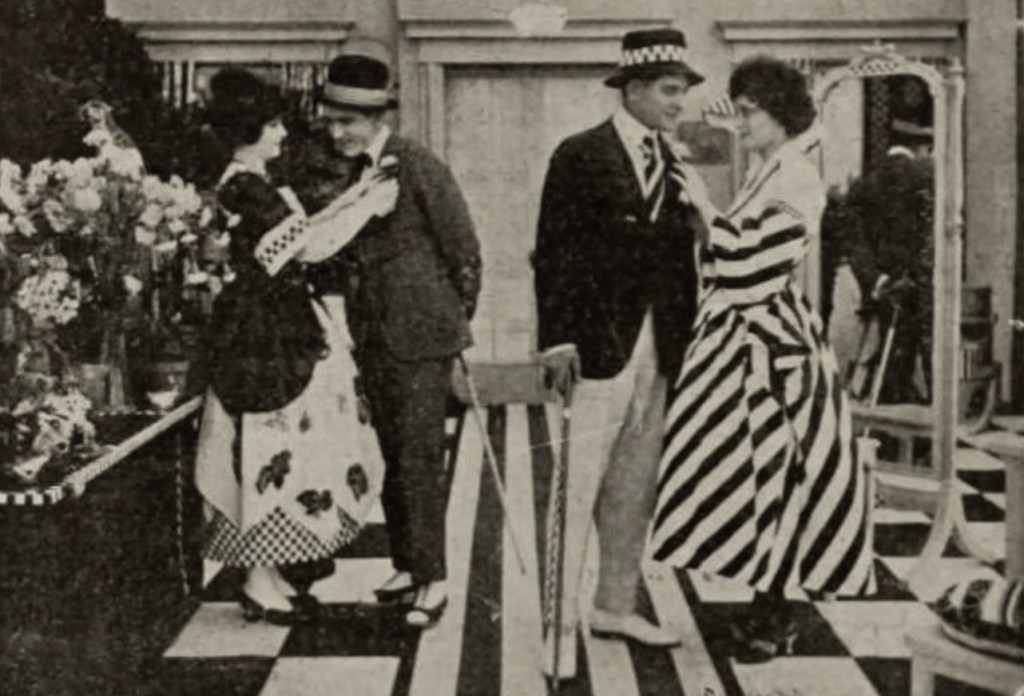

When I was a post-graduate intern at George Eastman Museum in the mid-1970s, I was sent by the Film Department to Yonkers, New York, to deliver a 28mm print of The Yellow Girl (1915) to Don and Karl Malkames; Father and son both had been storied cameramen in the New York film scene going back to the 1930s. They had built a 28mm gate for their home-made optical printer, so GEM could begin preserving their huge “3-M Company Collection” of 28mm, of which The Yellow Girl was the most sensational find, its modernist set and costume design unlike anything else seen at the time. Credit for that find went to Marshall Deutelbaum and George Pratt, my mentors. The Malkames had already done similar work for parts of MOMA’s Biograph Negative Film Collection, which required restoring a non-standard sprocket-hole system printer. Talking to the two veterans, I realized that film technology, itself constantly changing, also had to be preserved, otherwise the job of making film history accessible would not be possible. At Eastman I got to explore the “Equipment Collection,” but until that moment, I had only seen obsolete technology’s historical, but not its practical value. I also understood that the medium of film and the institution of cinema was material-based in the extreme, an epiphany whose full force I would only really understand after we moved into the virtual world of digitality; Materiality itself has become obsolete.

The Malkames are mentioned twice in Tales from the Vaults. Film Technology over the Years and across Continents/Histoires d’appareils. La technologie du cinema á travers les années et les continents, a dual-language publication of FIAF (Fédération international des Archivs du Film), edited by Louis Pelletier and Rachel Stoeltje. The book, itself an international cooperation, reinforces the point that the artifacts of film technology, the hardware, need to be preserved and studied. In compiling a richly illustrated coffee-table-sized book with alphabetically organized entries, the editors thus narrate and illustrate the interplay between film technology, film archeology, film preservation, and film aesthetics. Dozens and dozens of authors, literally from around the globe, relate fascinating stories of exactly 100 objects, material remnants from the analog world of moving image production and exhibition.

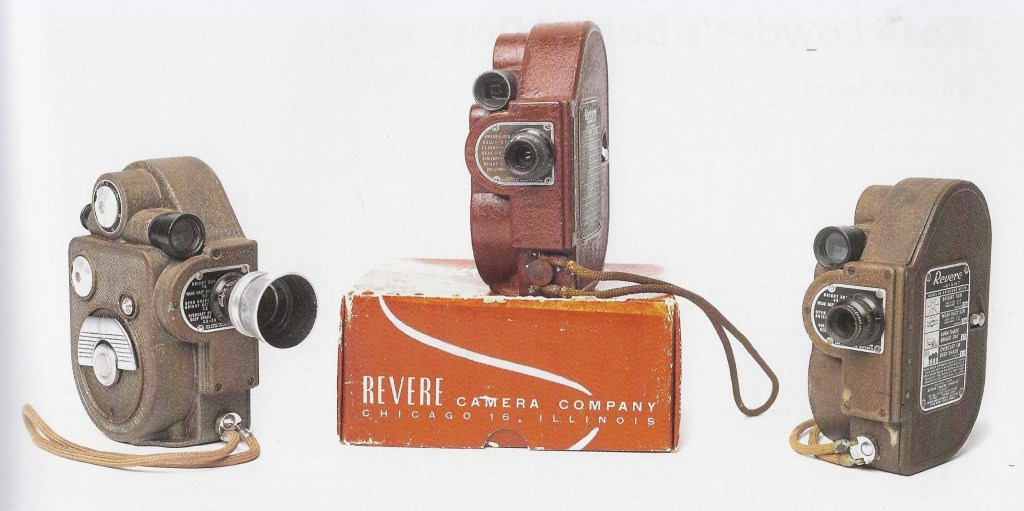

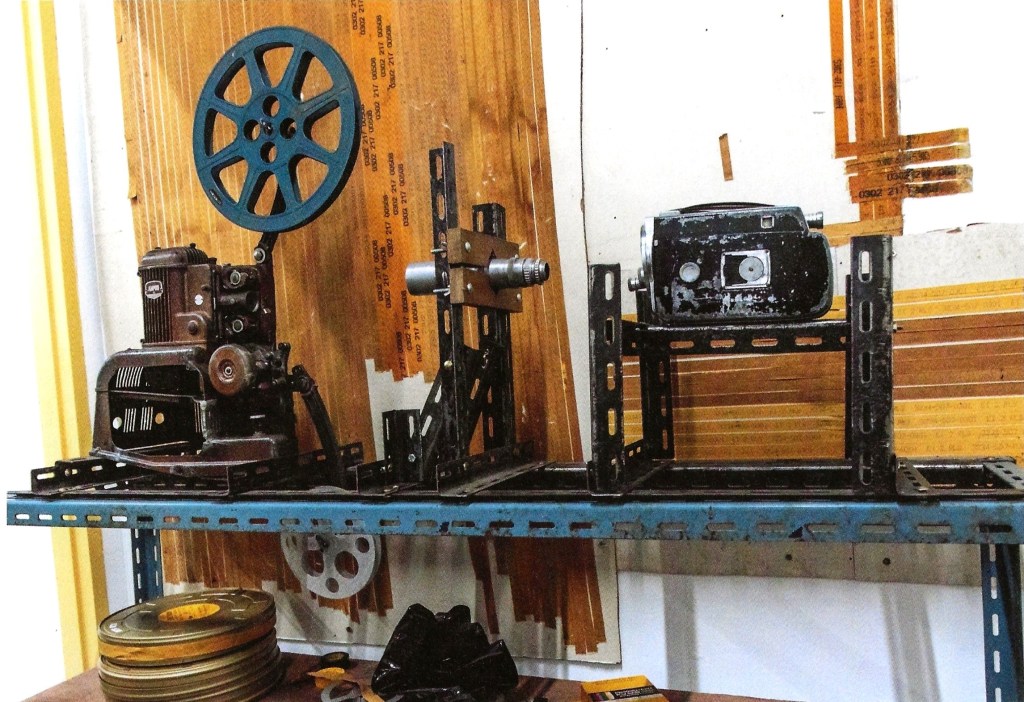

The 100 encompass everything from film cameras to projectors, optical printers to VCRs, pre-cinema optical toys to mobile projection vans, editing tables, film splicers, flip books, and more, industrial-produced and home-made. Pelletier calls these technical devices “the ghostwriters of film” because “cameras and microphones are kept off-screen, the editing benches and the printers toil in the dark….” (p. 30) Until recently, film object collections were stepchildren in most moving image archives, often in deep storage, in the dark, while film restorations gleamed in the light of LCD screens. While I was at UCLA FTVA, the extensive television set and equipment archive was finally put into an archival environment and curated in open storage; Mark Quigley’s entry on the Smith 2” Videotape Splicer describes that collection’s history.

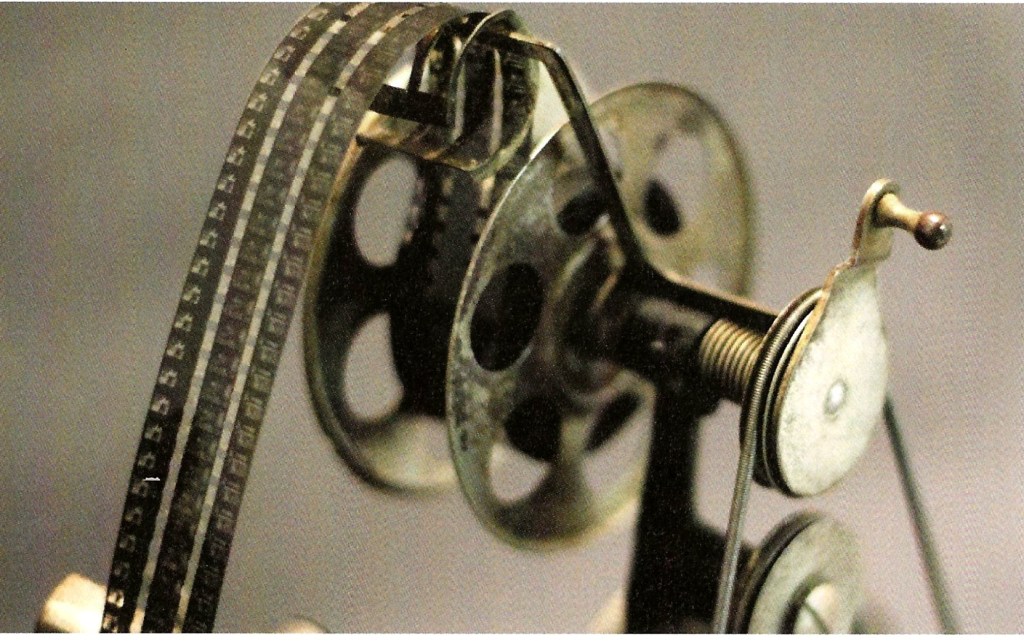

Apart from the physical descriptions of the objects and their utilization, entries often relate the circumstances of the object’s survival and their eventual entrance into an archive. The journeys such objects took, moving from utilitarian purpose to obsolescence, also visualize the relationships of cinema pioneers to film collectors and moving image archivists, the last named often involved in real detective work and donor cultivation. For example, the 1908 Biograph Printer mentioned above had been salvaged by William L. Jamison, a motion picture pioneer who had started in Edison’s Black Maria studio and was now a “field investigator” for MOMA. He and Biograph cameraman Billy Bitzer refurbished the printer in 1940 and began making prints from the negatives that Jamison had also salvaged from the studios in the Bronx. The printer then fell into disuse, only to be revived by the Malkames team in 1969. Then, there is the story of the Edison Home Kinetoscope film projector, introduced in 1912, which screened 22mmm films with three rows of images, running forward, then backward, then forward again. The USC H.M. Hefner Moving Image Archive acquired the amateur projector in 1968 from Sol Lesser, Hollywood B-film producer and passionate film technology collector, who as early as the 1930s began dreaming of a film museum. Curator Dino Everett and Marsha Gordon recently demonstrated the Edison projector, using 100-year-old film.

Janneke van Dalen sums up these preservation narratives best when she comments on the stories of an Austrian Film Museum archivist and film cutter: “Ms. Schlemmer’s interconnected stories and practice make us aware that a film collection is not just a storage space full of films and objects, but a living thing; an interplay between space, objects, and people in which the technical is connected to the stories behind the films, and inalienably linked to the people preserving them.” (p. 118)

Another fascinating thread in Tales from the Vaults celebrates the medium’s technological dead ends, engineered objects that either were unsuccessful commercially or never made it beyond a prototype, undergirding the theory of film’s discontinuous development, moving forward in fits and starts, rather than in linear time. There is e.g. the Alexeieff/Parker Pinscreen, used by the animation artists to create Night on Bald Mountain (1933), considered by many a surrealist animation masterpiece. Alexandre A. and Claire P. had built an animation stand with 500,000 pins held into place by paraffin wax which were manipulated and filmed frame b frame. Until recently, no other artist had ever used the device. On the other hand, Alexandre Medvedkin’s 16mm Machine Gun Camera, which was invented for use by newsreel cameramen on the Russian war front between 1942 and 1945, outlived its utility once the “Great Patriotic War” ended. The surviving camera gun saw battle action during the assault on Königsberg, East Prussia, some of its footage appearing in the documentary Königsberg (1945). Chris. Marker celebrates Medvedkin in The Last Bolshevik (1993).

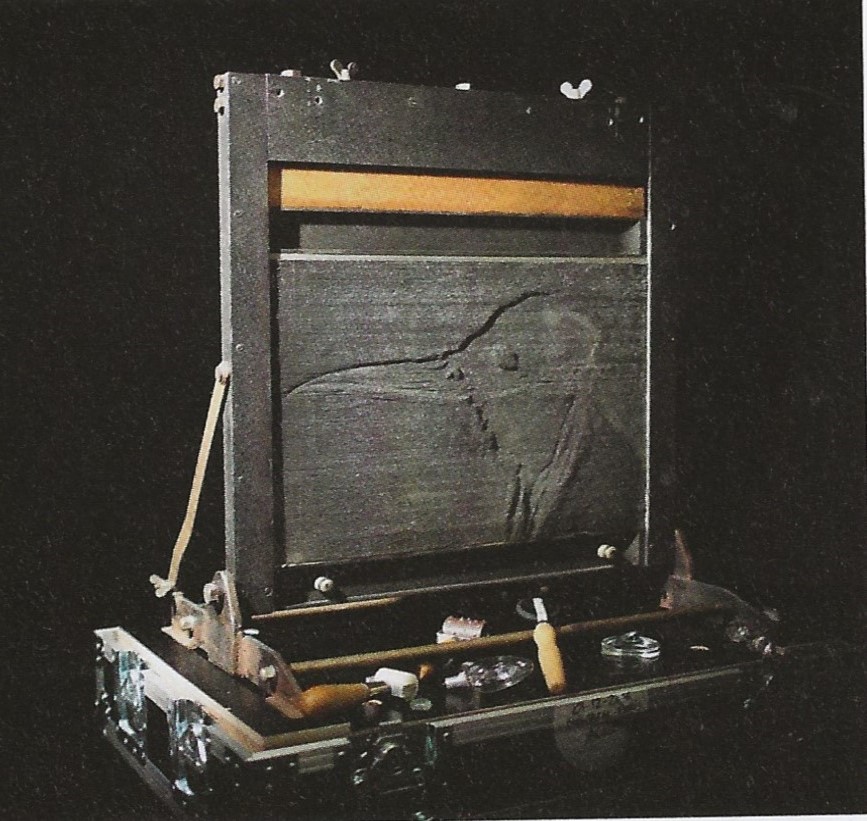

Many of the entries not only document the far-flung distribution of film technical equipment but also local modifications of the same. The Croatian Cinematheque now houses Aleksandar Gerasimov’s jerry-rigged sound film camera, which he built around 1930 using two existing silent 35mm cameras, one for image, and one for sound, since the local School of Public Health could not afford new sound film cameras. Then there is a 1910 Pathé Frères Grand Modèle Camera, built in Paris, which was used by Argentine film pioneer Mario Gallo in his pre-World War I film productions; he had purchased the camera from local film distributor Max Glücksmann before it ended in the collection of the Museo del Cine Pablo C. Ducrós Hicken, Buenos Aires.

One question I would have liked to see authors and editors address, is the elephant in the room, the above-mentioned digitality. If an impetus to collect these objects was in part to make new analog preservation copies, how does that change an object’s utility value when computers can retrieve information from almost any medium? How do the material archives of cinema not become obsolete in the face of AI and digital access? For me, the answer lies in our hunger for the real. Until algorithms can reproduce touch, smell, and sight in seamless images, – faculties needed for survival by our ancestors, – we will continue to hunger for the real and the world of objects. But that may be a generational p.o.v., I’m afraid.

In conclusion, Tales from the Vaults is a great read because it allows us to revel in the real. Whether you skip around between the entries or read alphabetically, each object has its own unique story which also illustrates how archives come into existence.

<

div dir=”ltr”>Thanks Chris, fascinating! Your scholarship, writing and rigor are impressive and illuminating!

<

div>…hope all is good! When it cools down let’s do dim sum!

Cheers!Freida freidamock.

<

div dir=”ltr”>

<

blockquote type=”cite”>

LikeLike

I appreciate you reading my blog. CHRIS

LikeLike

A wonderful blog, thank you! One correction. Alexieff and Parker gave their pinscreen to Jacques Drouin who was the only student of theirs who understood the technique. He won an Oscar using it. Jacques let John Canemaker and I play with it for a few minutes back in the day.

LikeLike