Archival Spaces 327

A Mid-Summer Night’s Dream (1925) restored

Uploaded 4 August 2023

One of the films I was most looking forward to at the San Francisco Silent Film Festival was the world premiere of the previously lost German film, A Mid-Summer Night’s Dream (1925) because I had as Director of UCLA Film & Television Archive initiated the project. Another bonus was the screening on Thursday of Die groβe Liebe einer kleinen Tänzerin (1924), a short puppet film that premiered in Bonn last year, then screened in Pordenone, and was co-directed by Alfred Zeisler, who coincidentally I have been researching for the past several months. Both films reverberate in different ways with the legacy of German Expressionism, which by the mid-1920s had given way to New Realism. Zeisler would go on to be a semi-important commercial director and one of four producers at UFA in the early 1930s, on par with Pommer, Stapnenhorst, and Duday, before emigrating to America.

The puppet short, The Great Love of a Little Dancer was originally to be called “The Cabinet of Dr. Larifari,” a title which more directly references, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920), which the film satirizes. Like Caligari, the story takes place on a fairground where Dr. Larifari, a magician, is in love with Esmarelda, the little dancer whose heart belongs to the lion tamer, Leonidas (who looks suspiciously like Harry Piel). Rebuked, Larifari puts a curse on any man who looks at Esmarelda, literally turning their heads around. Like Caligari who morphs into the head psychiatrist in the asylum, Larifari and Dr. Crymurder (to whom Esmarelda flees) are one and the same. The film seemingly ends tragically: Leonidas without a head, Larifai eaten by the lion, and Esmarelda committing suicide by falling off a bench and breaking into pieces but it’s only a dream. To make sure the audience understands the faux happy end, the film ends self-reflexively with the lovers being packed in a box by the puppeteer’s hands. Both the set design and the animated inter-titles, likewise pay homage to Caligari‘s Expressionism.

The film was the first of two short puppet films made by Picolo-Film Co,. which was founded by Zeisler and his co-director Viktor Abel, who had previously been Zeisler’s writing partner on a couple Harry Piel adventure films and would sporadically work with Zeisler at UFA. The puppets were from the famous Paul Schwiegerling Puppet Theater which Walter Benjamin had seen in Bern in 1918, then never heard of again: “It was more beautiful than anything you could imagine. Schwiegerling invented the so-called ‘transformation puppets,’ or ‘metamorphoses.’ His marionette theater was actually more of a magician’s den.” Transformation meant the puppets could split into separate body parts, as well as change shapes. The digital restoration from the only surviving nitrate print was handled by the Deutsches Filminstitut in Frankfurt.

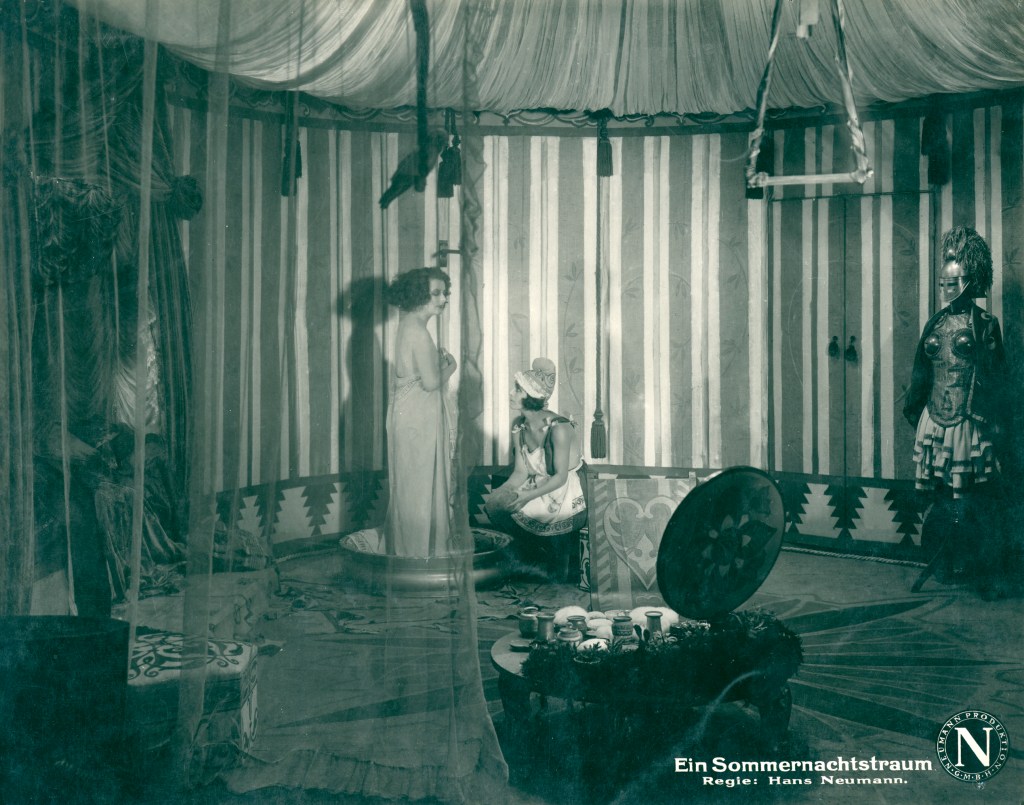

In Summer of 2011, the UCLA film archive got a call from the family of a deceased film collector in Oregon who had amassed over 220,000 feet of nitrate film, much of it from the silent era. His idea to preserve the material was to pack it in machine oil, like sardines, which miraculously worked, since we found only some nitrate decomposition. Ralph Sargent’s Film Technology cleaned the reels by hand several times before putting the films through their sonic cleaner; a first pass of a single oil-soaked reel had rendered the machine’s cleaning fluid useless. One particular title, Wood Love (1928), turned out to be the long-lost American release version of Ein Sommernachtstraum/A Midsummer Night’s Dream, directed by Hans Neumann.

Max Reinhardt made theatre history at the Neues Theater in 1905 with his staging of Shakespeare’s play, the forest on a revolving stage, reviving the production thirteen times in Berlin and Salzburg. In America, Reinhardt’s Hollywood Bowl production in 1934 was then adapted by Reinhardt and William Dieterle for Warner Brothers and released the next year. Here now was an earlier filmed version that featured numerous Reinhardt actors, as well as Reinhardt’s costuming and mise en scene, based on the visual evidence of the 1934 film.

Even though the German Historical Museum in Berlin had turned up a fragment of A Midsummer Night’s Dream in the 1990s, and even though the role of Puck was played by the eccentric dancer, Valeska Gert, whose legendary stage performances were not documented on film – she had appeared in most famously in The Joyless Street (1925) and The Diary of a Lost Girl (1929) – I spent several years unsuccessfully trying to get the Germans to consider financing a restoration. They were not interested. Happily, the Film Foundation eventually funded the project, which was started by Scott MacQueen and finished by Miki Schannon after my own departure from the Archive.

Unfortunately, Reinhardt’s satirical prologue – not in Shakespeare – of Hippolyta’s Amazonians attacking the Athenian Army of Theseus was removed from the Anglo-American release, so it has been hinted at with surviving publicity stills from the German release. Also removed from the American version were many of Reinhardt’s modernisms, including the use of telephones, since the impresario had tried to make the play more accessible by adding humor and reworking A.W. Schlegel’s archaic German translation into a modern idiom. The preservationists were able to use the German censorship records to reconstruct the satiric modernity of the original titles, rather than the Shakespearean titles of the American release. Among the A-List actors in the film, all of whom had acted in Reinhardt’s Deutsches Theater: Hans Albers, Tamara Geva, Werner Krauss, Fritz Rasp, Ruth Weyher, Paul Biensfeld, and Alexander Granach.

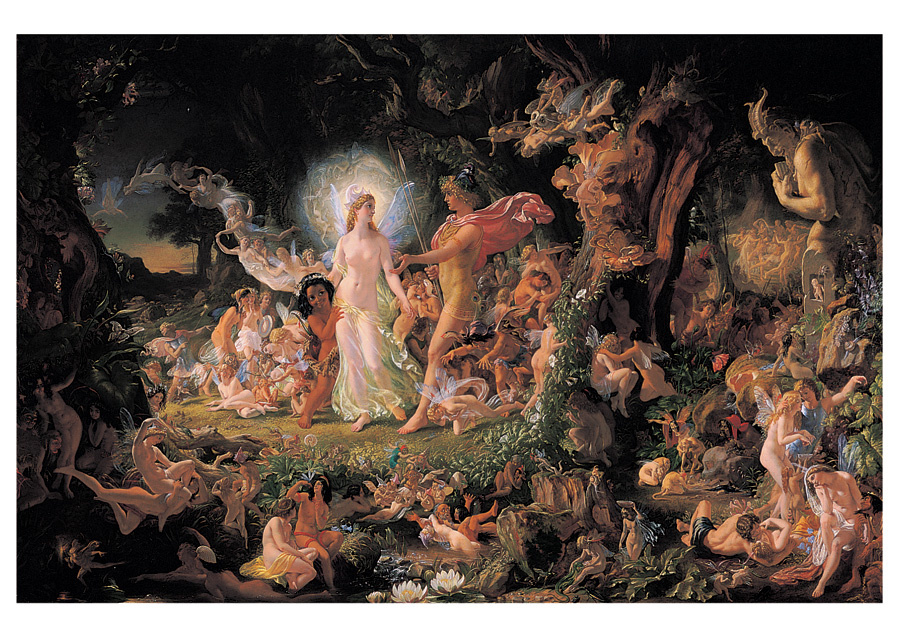

However, what stood out for me was the technical achievement of cameramen Guido Seeber and Reimer Kuntze. Nearly half the film consists of double exposures, as the wood nymphs, satyrs, and spirits frolic in the night, their bodies and flowing gowns visible but also translucent. Such super-impositions would have had to be done in-camera – optical printers had not yet been invented – so it must have taken a huge amount of trial and error with lighting on the Staken Studio’s massive forest set. It is also a specifically cinematic device that would not have been possible in Reinhardt’s theatre staging of the play. As Jay Weissberg notes in his catalog entry, set designer Ernö Metzner’s art direction also references 19th-century fairy paintings by Léon Frédéric, John Anster Fitzgerald, and Joseph Noël Paton.

Another thoroughly modern aspect of the production was its gender-bending. While Oberon, the King of the Fairies, played by female dancer Tamara Geva – wearing a headdress that would reappear in the 1934 film – is mysteriously androgynous, just as Valeska Gert’s Puck is played as gay and Hippolyta is more interested in women than in the pursuing Theseus; Gert was of course openly lesbian, even in the 1920s. Then, there are the actors in the play within a play who appear in female dress with mustaches, proudly in drag. Indeed, much of the frolicking by gender-unspecific spirits read as gay.

This may not be Fritz Lang but we are truly fortunate to now have this Reinhardt-inspired A Midsummer Night’s Dream, which documents the spirit of 1920s Berlin as much as Dr. Mabuse.

And the Germans were not interested … sounds like the material for an extra story….

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear Chris,

I was delighted to see the Wood Love restoration project that you initiated over 10 years ago (and we discussed from time to time) finally come to fruition! Innovative camerawork in the film really does evoke the enchanted spirit world of Shakespeare’s forest. Your blog also effectively highlights the rich Reinhardt connection.

May Tony and I publish it in the fall edition of our website WeimarCinema.orghttps://www.weimarcinema.org/?

Best wishes,

Cynthia

LikeLike