Archival Spaces 239

The Czechoslovak Legions in World War I

Uploaded March 27, 2020

In the past couple years, I have written blogs about my dad, Jerome (Jaromir) Horák, who was both a concentration camp survivor (https://www.cinema.ucla.edu/blogs/archival-spaces/2014/11/21/international-students-day) and a refugee from Communist Czechoslovakia (https://www.cinema.ucla.edu/blogs/archival-spaces/2018/08/31/abduction-petr-zenkl), and whose birthday it is today. More recently, I have been researching my father’s father, Jan Horák, and namesake, who was a member of the Czechoslovak Legions during World War I. According to the Central Military Archive of the Czech Republic, Děde, as we children called my grandfather, joined the Czechoslovak Legion on March 23, 1918, almost exactly 102 years ago. For more than eighty years, a large silk-stitched Gobelin of a Siberian tiger hung in the dining room of my grandparents home in Prague-Vysočany, which grandfather had purchased in 1920 in Vladivostok or possibly China on the long, ship’s voyage home from Russia’s Pacific coast through the Suez Canal to Trieste, returning to Prague in April 1920, more than 18 months after the Armistice. Throughout the latter half of the 20th century, the history of the Czech Legions in WWI was suppressed by the Communists for reasons that will become clear below, and only recently has a spate of new research brought to light their amazing story.

The Czechoslovak Legions were formed in Russia, France, and Italy in 1914-1918, before the Czech nation even came into existence, and consisted of deserters and P.O.W.s from the Austro-Hungarian Army, who wanted to fight against the Central Powers on the side of the Triple Entente, in the hopes that their sacrifice would encourage the Allied Powers to give the Czechs and Slovaks their own independent country, rather than remain under the yoke of the Austrian Habsburg Empire, as they had been for 300 years. In Imperial Russia, the original core of the Legion, the Česká družina, was constituted as a unit of the Russian Third Army as early as August 1914, made up of Czech and Slovak residents in the Tsarist Empire. Officers and enlisted men alike addressed each other as “bratr” (brother). Until August 1915, the Russian military command had reservations about accepting Austro-Hungarian deserters and P.O.W.s into their army, given the 2nd Hague Convention’s (1907) prohibition against P.O.W.s joining the armies of their respective enemy, because they would lose P.O.W. protections and be subject to execution as traitors, if caught again. Nevertheless, P.O.W.s continued to join, so that by 1917, two Czechoslovak Rifle Regiments had been created, who fought heroically at the Battle of Zborov on the Ukrainian front in July 1917, overrunning the Austrian trenches. By the beginning of 1918, the Legion numbered over 40,000 soldiers in eight regiments.

Born in Prostějov (Proßnitz, Austro-Hungary) in central Moravia in February 1886, Jan Horák had moved to Prague to study at university, and was probably already working in Vysočany at ČKD (Českomoravská Kolben-Daněk), one of the country’s largest producers of heavy machinery, when he joined the Austro-Hungarian Army in late 1914 or early 1915. Given the rank of Lieutenant, he was assigned somewhat inexplicably to the newly formed 14th Rifle Battalion, 16th Infantry Brigade, a unit that was made up almost exclusively of Polish and Ruthenians from Galicia (Ruthenia would become a part of the new Czechoslovak Republic until annexed by the Soviet Union in 1945). The Brigade was sent to the Western Ukraine, where the Russian Imperial Army was attempting to invade Austro-Hungary through the Carpathian Mountains near Nadvorna, just South of Liviv (Lemberg); there, my grandfather was captured on June 1, 1915. He was initially sent to Kiev, where he was formally registered as a P.O.W., then transferred to a camp near Samara, on the eastern bank of the Volga River in Russia, where he spent the next 31 months, before joining the Czech Legion with the rank of Private. Another inmate of the camp was Jaroslav Hašek, later author of the classic antiwar novel, The Good Soldier Švejk.

By the time Horák put on a Czech uniform, the Russian Revolution had occurred and the new Bolshevik Government had signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (March 3, 1918), which ended Russia’s participation in the war, leaving the Czechoslovaks stranded. A month earlier, the Germans had launched a counter-offensive in Ukraine, forcing the Czechs to defend successfully Kiev and cover their own retreat. Weeks later, Tomaš Masaryk, the leader of the Czechoslovak independence movement and soon to become first President of the Republic (October 1918), was in Russia to enlist Czech and Slovak P.O.W.’s in the Legion, and negotiate with Lenin the transfer of the Legion to the Western Front via Archangel or Vladivostok. He also assured the Red Army in Kiev that the Czechs would maintain strict neutrality in the beginning civil war between Reds and Whites. Several thousand leftist Czechs and Slovaks actually succumbed to offers of better pay and joined the Red Army, including Hašek.

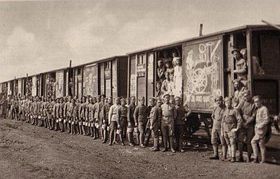

But the Bolsheviks also sent mixed messages, approving the transfer of the Legion one day, then ordering the Red Army to take all Legionnaires from their trains, shoot them or put them in labor battalions or fight for the Reds. While a small portion reached Archangel, the greater part of the Legion, now nominally under the command of the French Army, converged on the Trans-Siberian railroad, first giving up most of their weapons to the Bolsheviks, as per the Penza Agreement (March 26), then taking them back when they were continually attacked by Bolshevik troops (May 26), who cared little about orders from Moscow. By June 1918 the Legion controlled all 2500 miles of rail west of Irkutsk in Siberia with over 60 Legion troop trains running East; in September they owned all 6,000 miles to Vladivostok.

By then, 40% of the Legion, including my grandfather, had made it to Vladivostok, only to be ordered to return West, either to open up a new Eastern Front against the Austro-Germans, or intervene in the Civil War against the Bolsheviks (along with U.S., Japanese, and British troops), or relieve their brethren still trapped in European Russia (west of Penza), the Allies couldn’t decide what they wanted. Ultimately, the Legion threw their lot with the Allies and White Russians, who controlled much of Siberia under Admiral Alexandr Kolchak, keeping the Trans-Siberian open (without the promised help from the Allies) for much of 1919, but quickly becoming disillusioned with Kolchak’s anti-democratic reign. They eventually captured Kolchak, handing him over to the Bolsheviks, while steadily retreating as the Bolsheviks conquered territory from West to East. In February 1920, the Legions signed an Armistice with the Reds, allowing them to evacuate from Vladivostok. The last of close to 60,000 Legionnaires left the Pacific port in September 1920, but by then my grandfather had been home for months and impregnated my grandmother, who gave birth to my father on March 27, 1921.

Between the World Wars, the members of the Czech Legions were treated as heroes, whether in civilian life or rising in the ranks of the Czechoslovak Army, like my great uncle, General Josef Kohoutek, who had joined the Legion in Italy, became the head of Czech Army Intelligence, only to be executed by the Nazis at Berlin-Plötzensee in September 1942, in reprisal for the Reinhold Heydrich assassination. After the Communist Putsch in Czechoslovakia, the Legion’s reunions were outlawed, and its history suppressed. Unfortunately, I didn’t meet my Děde, until he was 79, by which time he was suffering from dementia. When my grandfather died in March 1969, only a handful of aging Legionnaires were allowed to form a color guard to accompany him to his last resting place.