Archival Spaces 271

Ozaphan, 16mm on Cellophane

Uploaded 11 June 2021

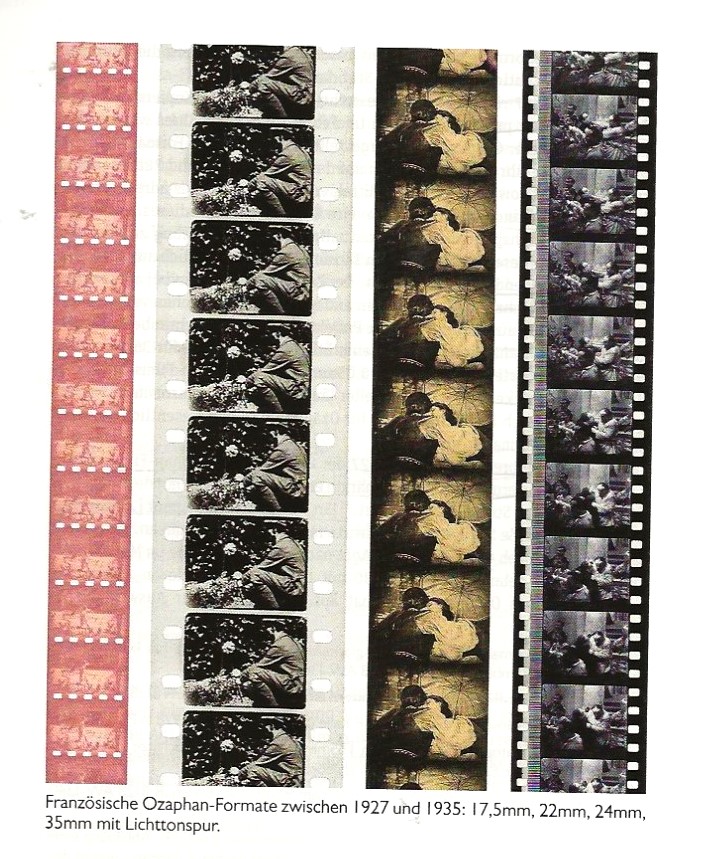

Ozaphan was a non-flammable safety film format marketed for home use in France and Germany from the late 1920s to the 1950s, which had the peculiarity that it neither used a conventional photographic emulsion, nor was its base di-acetate. Rather, Ozaphan employed a system of image reproduction akin to blue line printing on a cellophane base. Despite the fact that it could not be utilized as a production medium, but only as a projection format, it was relatively popular as a distribution medium for amateurs wishing to screen commercial fiction, documentary, and animated films in their own homes. Ozaphan was produced through a cooperation between the French Le Cellophane, Agfa, and the German manufacturer Kalle & Co. AG. Despite attempts to form a French-German-American partnership in 1937-38 to distribute Ozaphan films in the United States, negotiations broke down, due to resistance from Ansco, the American subsidiary of Agfa, which saw as a competitor to its 16mm film. A new monograph by Ralf Forster and Jeanpaul Goergen, Heimkino auf Ozaphan. Mediengeschichte eines vergessenen Filmmaterials (CineGraph Babelsberg, 2021) details the history of this weird film format.

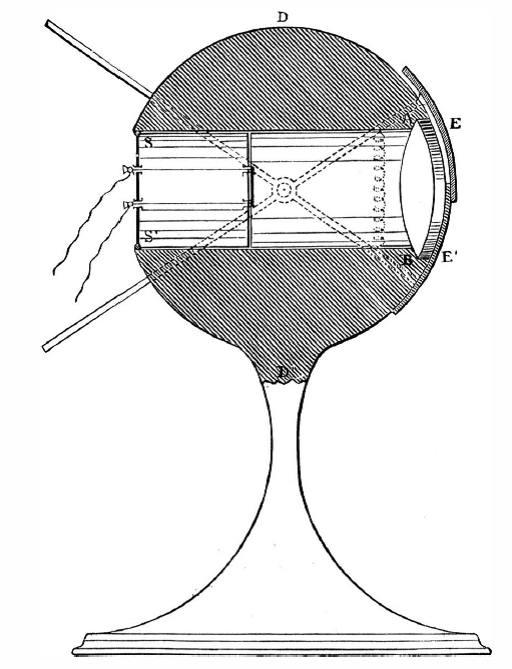

Cellophane was invented and patented between 1908-10 by the Swiss chemist, Jacques Edwin Brandenberger, as a clear, waterproof tablecloth for restaurant use, but was quickly marketed as packaging material for everything from food and candies to drugs and books. By 1912, Whitman Candy Company was packaging their sampler in cellophane. In 1924, Brandenberger sold the rights to cellophane production in America to E. I. du Pont de Nemours. While cellophane was contemplated as a base for photographic film, the fact that it lost its dimensionality when soaked in developer, made it unsuitable. Invented in 1917, Kalle & Co. introduced a diazotype photographic process in 1924, under the brand name Ozalid, which was able to accurately reproduce blue-line drawings on paper. Ozalid’s dry developing process used gas, rather than water, making a marriage of the two technologies feasible.

With the expansion of the amateur film market in the 1920s, numerous raw film manufacturers attempted to find a safe alternative to highly flammable nitrate film. Pathé introduced a 9.5mm format in 1922 for their “Baby-Pathé” camera and projector, and Eastman Kodak brought their 16mm system to market in 1924, both based on a di-acetate based film. Shortly thereafter, Kalle, which had been absorbed by I.G. Farben, formed a partnership with Le Cellophane S.A. to create a non-flammable amateur film format, Ozaphan, which was also significantly cheaper to produce than di-acetate. In April 1928, Agfa introduced its 16mm Ozaphan film, having marketed a 22mm format (Edison) a year earlier, and two years later an X-ray film and film for soundtracks.

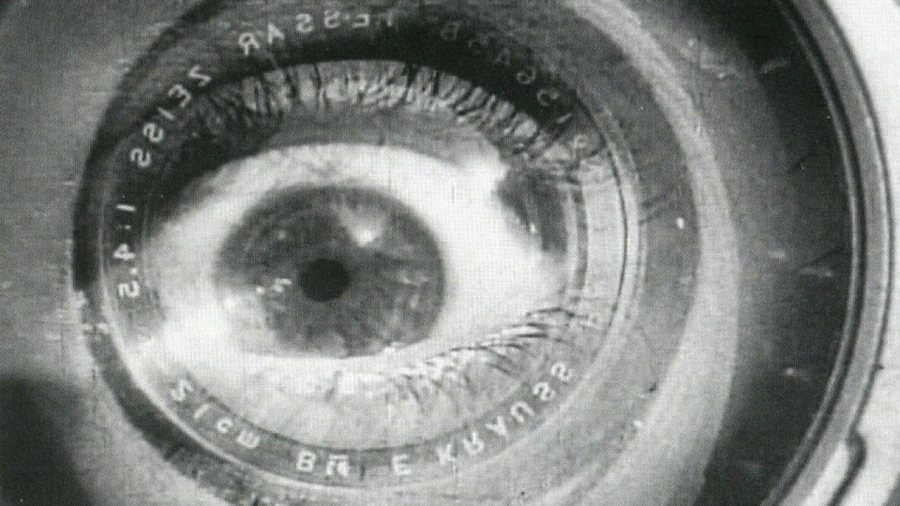

One advantage of Ozaphan was it was approximately half as thick as di-acetate, decreasing shipping costs, and also cheaper to produce because it did not use silver salts. Instead, cellophane was impregnated with a photosensitive ferric compound and dried. Utilizing a 16mm photochemical positive print, reduced from a 35mm negative as a matrix, Ozaphan prints were contact-printed under light, then developed under pressure in ammonia gas, a process that took 6-7 hours. Despite increased cost for matrices and developing, the cost of a finished Ozaphan film was 15 Pfennings, rather than 90 Pfennings per meter for di-acetate. This process obviously precluded the production of images in a camera, and was thus only used to make copies. Drawbacks to the process were that cellophane continued to have dimensional and shrinkage issues, and the quality of the yellow tinted black and white image was inferior to photographic film, lacking most grey tones.

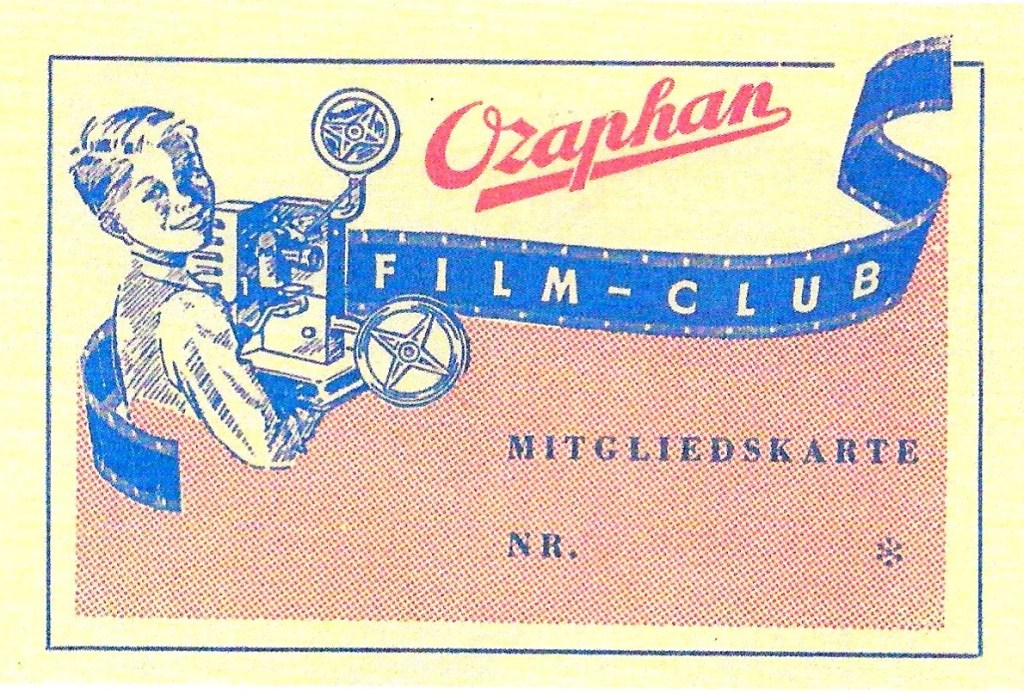

Nevertheless, Ozaphan became a popular amateur projection film format in Europe. By 1934, Agfa was distributing more than seventy-five titles (all of them silent) in the Ozaphan format. Virtually all of them were severely abridged versions of previously released commercial films, including German “Kultur” films from the Ufa, and other companies, and even American films, like “Charlie Chaplin in Hollywood.” Agfa, and after 1937, Kalle, continued to distribute films in a large catalog during the Third Reich, including Nazi propaganda films. And while the company went dormant in 1945, it was revived in 1949 in the German Federal Republic and continued to operate until 1958, even spawning an Ozaphan-Film Club movement with more than 10,000 members. As a result, at least two generations of amateur film lovers were influenced by the process. Several hundred Ozaphan prints survive in German film archives, but copying them was impossible until digital technologies were introduced.

Film history is filled with such anomalies, technological dead-ends, and brief shooting stars! As a non-photographic process, Ozaphan was one of the most interesting. For those who don’t read German, Ralf Forster and Jeanpaul Goergen published their preliminary research, “Ozaphan: Home Cinema on Cellophane,” in Film History, No. 4, 2007, 372-383.