Archival Spaces 320

Orphan Film Symposium: All-Television Edition

Uploaded 28 April 2023

For the first time since May 2011, UCLA Film & Television Archive hosted the Orphan Film Symposium with New York University, again at the Billy Wilder Theater. Co-curated by Orphans founder and NYU professor Dan Streible and John H. Mitchell Curator of Television at UCLA Mark Quigley, the 1 ½ day event drew television archivists and researchers from across the United States, many of whom presented their treasures of rarely or never seen television footage. After welcomes by UCLA Film & Television Archive Director May Hong HaDuong and Streible, with Streible asking “What was Television,” the proceedings began shortly before noon.

After Jeff Bickel, UCLA Film & Television newsreel archivist introduced some Hearst Metrotone News footage from 1931 of John Baird, one of the inventors of mechanical television, Mark Quigley presented a previously lost closed-circuit broadcast of a CBS press conference in 1956, introducing the first five Playhouse 90 (1956-61)programs, soon to become one of the most storied omnibus drama shows of the 1950s. Running a then-unheard-of 90 minutes, the program eventually garnered 47 Emmy nominations and 19 wins, including four for “Requiem for a Heavyweight,” the second show in the series. Introduced by program producer Martin Manulis, the show featured a series of talking heads talking about the pleasures of making the program, including directors John Frankenheimer and Ralph Nelson, and actors Charleton Heston, Tab Hunter, Vincent Price, Jack Palance, Ed Wynn, Kim Hunter, Eddie Cantor, Peter Lorre, Boris Karloff, Frank Lovejoy, and Barbara Hale. CBS spared no expense to acquire well-established and respected Hollywood film actors for a new kind of television at 90 minutes, i.e. like films. The quality of the 35mm film print, blown up from two 16mm kinescopes was exceptional, allowing a more casual look at stars mugging for the camera as they struggle to read the teleprompter.

Next, Mike Mashon from the Library of Congress presented four clips from television pilots that never saw the light of a cathode ray, including The Family Upstairs (1955), a family sitcom on a two-story set, one camera moving between floors; It’s Joey (1954), featuring 21-year-old Joel Grey singing and dancing as if he were on a Broadway stage, rather than a 15’ x 15’ studio set; a Polly Bergen-Dick van Dyke game show, Nothing But the Truth (1956), revived the same year as To Tell the Truth (1956- present); and an even weirder Some Like It Hot (1961), which transforms the stars of Billy Wilder’s movie (Jack Lemon, Tony Curtis) through plastic surgery into the pilot’s players, ostensibly so they can escape the mob. Ruta Abolins, Peabody Awards archivist, closed out the evening with an amazing interview with singer James Brown, conducted in 1971 by a young, local, black Georgia TV station host, Willi Brown. In the interview, James Brown chides the host for asking “colored” questions, like a white man, rather than helping the community to liberate itself from the daily racism around them. Preaching black self-reliance, Brown endorsed Richard Nixon shortly after the interview. Yet, there is also something magnetic in James Brown’s on-camera performance, where left and right become one of many contradictions in Brown’s career.

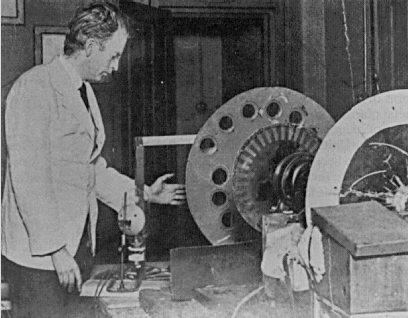

Day 2 began with Daniela Currò, Director of the Fox Movietone Archive in South Carolina, introducing a television test (1931) by Herbert E. Ives of the Bell Telephone Labs who is presenting his mechanical television system. Next, Margie Compton (U. Georgia, Brown Media Archives) showed a hilarious local game show sponsored by Purex Bleach, whose only goal was to give away as many bottles of the sponsor’s bleach as possible, naming contestants on air with their actual phone numbers and addresses. The mirth continued with Caroline Frick and Laura Treat from the Texas Archive of the Moving Image, showing numerous clips of car commercials, children’s shows, Cesar Romero made-up as Batman’s Joker being interviewed by what appeared to be a former lover, and alocal late-night terror show host, among others. Their humor-filled presentation was also deadly series, noting that 90% of all tv-programming before 1995 is now lost, and at least three States in the Union have no television collections at all. They named three major impediments to preserving tv: 1. Funding, which is very expensive; 2. Technical obsolescence; 3. Copyright restrictions.

The afternoon session on “Women Make Television” began with Melissa Dollman (Deserted Films) showing a short clip from a 1955 local children’s program, followed by a hilarious piece, introduced by Maya Smukler (UCLA F&TV Archive), in which local L.A. television host Mary McAdoo of Mary McAdoo at Home (1953) verbally spars with costume designer Edith Head about what kinds of clothes are appropriate for women who are not perfectly shaped with four or five mannequins to use as defensive or offensive weapons. Edith gives as good as she gets. The program revealed to what degree much of early television, especially local tv, was live and improvised, warts and all. The humor continued more seriously with Barbara Hammer’s avant-garde video short, T.V. Tart (1988), introduced by Amy Villarejo (UCLA School of Theatre, Film, and Television). In the highly manipulated electronic image, the late Barbara Hammer gorges herself on all manner of sweets and sugar, Hammer drawing in what is primarily an abstract film an analogy between tv consumption and candy. The program then took an even more serious turn with Juana Surárez (N.Y.U.), who has since 2015 been working on the preservation of Yuruparí (1983-86), a Colombian TV series of ethnographic documentaries about Afro-descendant and indigenous culture, directed by Gloria Triana and filmed in 16 mm and on video.

The final session of the afternoon saw Mark Quigley (with Shawne West) introduce Tom Reed’s For Member’s Only (1981-2011), a long-running independently produced African-American culture program. I remember when Mark first came to me in 2017 and announced he had visited Tom Reed, who was thinking of donating his collection. It would take several years of courting before Quigley was able to finally acquire this amazing collection of ¾” tapes from Reed, which document not only black culture and politics in L.A. for decades, but also black capitalism in the form of commercials. The afternoon concluded with legendary Chicano filmmaker Harry Gamboa’s Imperfecto (1983), a bizarre and comical video short that visualizes a Latino man as an asylum inmate seeking the truth, metaphorically describing the relationship between white mainstream power and Latin culture in Los Angeles. Chon Noriega (UCLA) introduced the video and interviewed Gamboa after the screening.

Unfortunately, I was not able to attend the evening’s programming, which focused on African-American television and video, presented by Orphan regulars, Walter Forsberg (Smithsonian) and Ina Archer, as well as Franklin A. Robinson, Jr., (Smithsonian), Blake McDowell (Smithsonian), Ellen Scott (UCLA), and Josslyn Luckett (NYU).