Archival Spaces 336

Danger Music… Between Film Comedy and Musical

Uploaded 8 December 2023

Over Thanksgiving weekend the Hamburg Cinegraph group invited scholars to the 36th International Film Historical Congress, “Danger Music… Between Film Comedy and Music,” which accompanied the “20th International Festival of German Film Patrimony,” held in Hamburg’s storied Metropolis cinema between 17 – 26 November. The main focus of the festival, as well as the conference, was the late Weimar period after the introduction of sound, in particular film operettas and musical comedies, although with side glances at individual films from the silent era, the Third Reich, postwar Germany and Hollywood (made by German émigrés). As a conference participant, I was only able to see the film program in the last four days, but still made numerous discoveries, given that many films from this period have only been recently discovered and preserved.

The Congress opened on 11-22 with a screening of Die grosse Sehnsucht/The Great Passion (1930, István Székely), a comedy about an ambitious extra, played by Camila Horn of Murnau’s Faust fame, who claws her way to film stardom but must in the process sacrifice her boyfriend. Like all early sound films, it includes several musical numbers, including “The Girl has Sex Appeal.”Not only does the film visualize the technical details of the new process of making films – shot at the UFA studios -, but also includes cameos by more than a dozen German film stars, including Lil Dagover, Anny Ondra, Olga Tschechowa, Charlotte Susa, Gustav Diesel, Karl Huszar-Puffy (Charles Puffy), Fritz Kortner, Franz Lederer, Fritz Rasp, Luis Trenker, and Conrad Veidt. I was particularly happy to see Francis Lederer, who left Germany for Hollywood before ever making a sound film; surprisingly, he spoke accent-free German, though born in Prague.

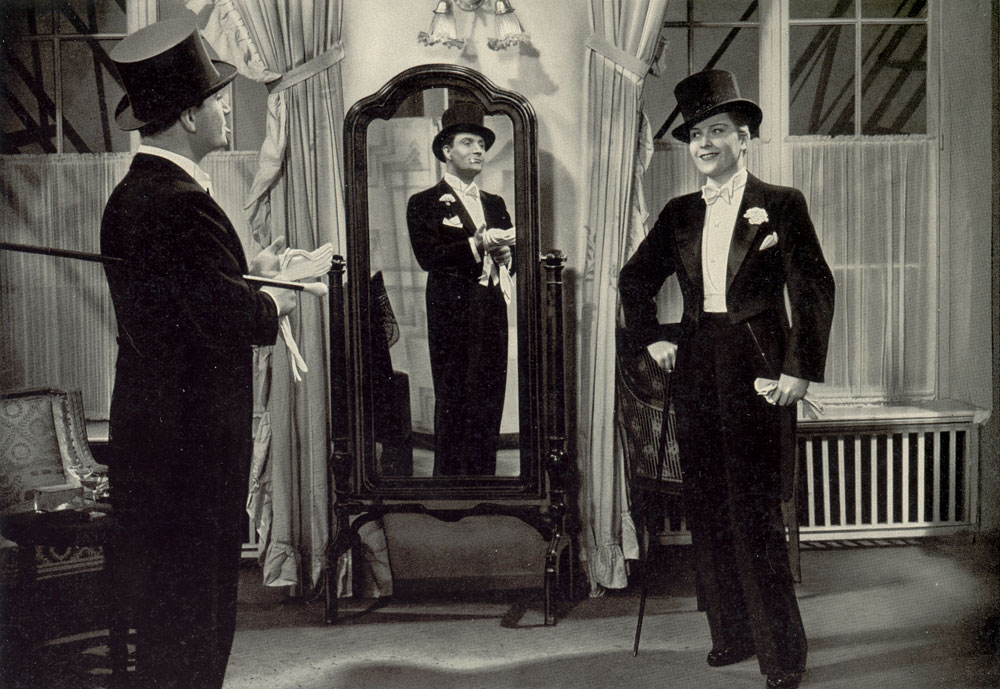

Bypassing well-known film operettas, like Wilhelm Thiele’s The Three From the Gas Station (1930) and Erik Charell’s The Congress Dances (1931), the festival screened Hanns Schwarz’s Ihre Hoheit befiehlt/Her Grace Commands (1931), based on a script co-written by Billy Wilder. A tongue-in-cheek homage to Lubitsch’s mythical central European Kingdoms, the film involves the romance of a young lieutenant (Willy Fritsch) and a princess (Käthe von Nagy), who meet incognito at a costume ball. The film is staged as a war of the sexes, which can only be resolved when the couple flees the demands of royal court etiquette, thus re-establishing the equality of their first encounter.

Billy Wilder’s last German film script, Ein blonder Traum/Happily Ever After (1932, Paul Martin) forsakes the aristocracy for the nether world of Germany’s working class during the Depression: A young homeless woman dreams of Hollywood film stardom (Lilian Harvey), but is loved by two window washers (Willy Fritsch and Willy Forst) who battle for her affection. Unlike Bertolt Brecht’s Kuhle Wampe(1932), which likewise plays in a homeless encampment, this UFA film calls not for revolution, but for the girl to give up her dreams, marry, and become a contended housewife. The film’s sexual politics presages the coming Third Reich, not a surprise, given UFA was controlled by Alfred Hugenberg and Hugenberg would enter Hitler’s first cabinet. Meanwhile, as if film mirrored life, Harvey would leave for Hollywood and a contract at Fox after completion of the film, but after four films she was back in (Hitler’s) Berlin, while Wilder would arrive in Hollywood 18 months later, a penniless refugee from Hitler.

Wilhelm Thiele’s Madame hat Ausgang/Amorous Adventure (1931) begins, like Her Grace Commands, with a costume ball, where a couple of working class singles meet, only she is an upper-class married woman (Liliane Haid) incognito and out for revenge against her philandering husband, while he’s a petit bourgeois bookbinder (Hans Brausewetter). Somewhat incredibly, she falls hard for the thoroughly conventional lover, so he is the one to send her back to her husband, understanding that he would never be able to give her a life of luxury. Both Blonde Dream and this film were composed by Werner Richard Heymann, who as an exile would join Lubitsch’s team in the late 1930s.

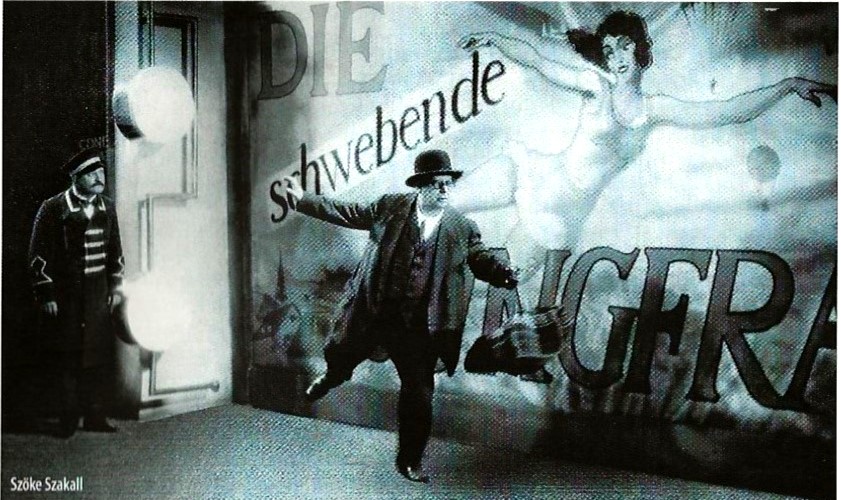

One film that had the audience in stitches, more comedy than musical, was Die schwebende Jungfrau/The Floating Virgin (1931, Carl Boese), starring Szöke “Cuddles” Szakall, and several other prominent comedians. The Hungarian actor became famous for playing a stranded exile in Casablanca, fracturing English, “What watch?” Ironically he was himself an exile, speaking perfect German as did many in Hungary’s Jewish community. Here, Szakall plays an uncle who creates chaos wherever he goes in a virtually incomprehensible plot involving a switched suitcase between Berlin and Hamburg. No matter, Szakall who got his nickname from Jack Warner, was the whole show. Not surprising then that “Cuddles” was always memorable, even if only in one scene

Andalusisische Nächte/Nights in Andalusia (1938) featured the Spanish film diva, Imperio Argentina, one of Adolf Hitler’s favorite actresses – he personally paid for her to come to Berlin to work at UFA – in an unauthorized version of Carmen sans Bizet’s music, where Carmen sings folk songs. Unlike the original, it is not Carmen who dies, but rather her soldier-lover, who sacrifices himself for the troops he previously betrayed, in keeping with the Nazi ethics of death for the Führer. Carmen also has a second lover, which shifts the central drama away from feminine desire to the male drama of competition for the female and duty to comrades. Imperio who was a mega star in Latin America, was certainly charismatic, unlike her dull co-star, but she she lacks agency in the narrative.

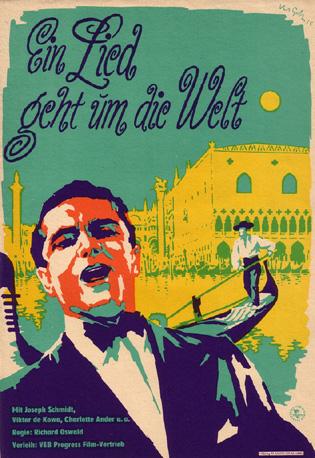

Ein Lied geht um die Welt/My Song Goes ‘Round the World (1933, Richard Oswald) starred the diminutive tenor, Joseph Schmidt, who became an international radio and recording star, but whose height (well under 5 feet) precluded a career on the opera stage. Semi-autobiographical, the film tells the story of a Venetian singer who despite his amazing classically-trained voice succeeds in radio, but loses the girl because of his size. To add insult to injury, it is his partner on stage and best friend who gets the girl. The Jewish-born Schmidt fled Germany on May 9, 1933, a day after the film’s premiere, attended by Goebbels, and three days after the mass book-burning of Jewish authors. After making several more films in Austria and the United Kingdom, he died in a Swiss internment camp in 1942.

Finally, extremely popular operatic tenor, Richard Tauber, was another victim of Nazi anti-Semitism, even though it is not even certain that his illegitimate father was Jewish. The first of several musical films produced by Tauber’s own film company, Ich glaub’ nie mehr wieder an einer Frau/Never Trust a Woman (1930, Max Reichmann) was one of the few musical melodramas in the festival. Tauber plays a man disillusioned with love, who returns home to Germany as a sailor. There he must stand by his young colleague, who falls in love with a prostitute, not knowing it is his own sister. In between the Sturm und Drang, Tauber gets to sing a lot of folk and sailor songs. While the film addresses a serious problem among Germany’s working classes, Tauber is a man of mystery, coyly deflecting any questions about his origins, but certainly not working class.

What this festival demonstrated was that beyond the art house classics by Fritz Lang, G.W. Pabst and Robert Siodmak, the German film industry produced numerous high-quality commercial music films in the early sound period. Unfortunately, Hitler would drive almost all of their makers into exile, including many composers, like Paul Abraham, Michael Eisemann, Artur Guttmann, W.R. Heymann, Friedrich Hollaender, Robert Stolz, and Franz Waxman.