Archival Spaces 348

Hollywoodland: Jewish Founders and the Making of a Movie Capital

Uploaded 31 May 2024

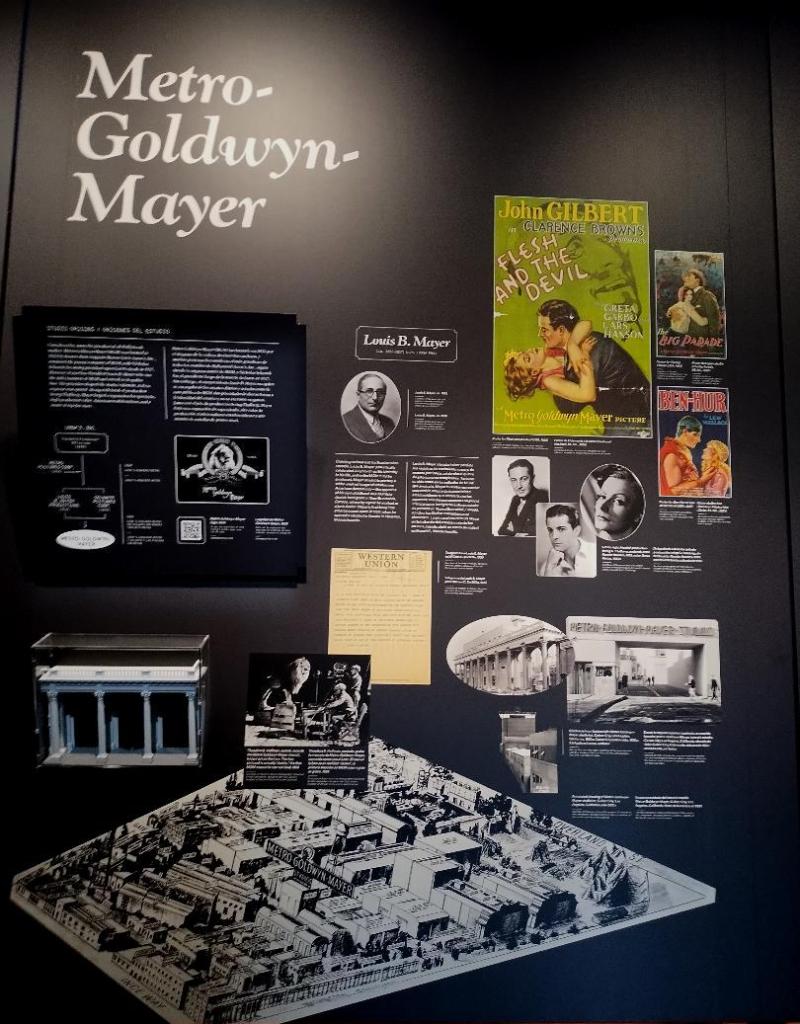

Two weeks ago, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences Academy Museum opened what most observers called their mea culpa exhibition on Hollywood’s Jewish Pioneers, “Hollywoodland: Jewish Founders and the Making of a Movie Capital,” which occupies a small gallery and is now part of the permanent exhibition. When the Museum opened two years ago, it was heavily criticized for creating a permanent exhibit on Hollywood that was all but Judenrein, a single display of Louis B. Mayer with an Oscar constituting the only Jewish reference in the many thousand square feet exhibition. Four months later, the Academy Museum announced its Jewish Pioneers exhibit to counter criticism. As The Times of Israel wrote (22 March 2022): “The museum’s announcement of its new permanent exhibition focused on Jews came only after the Academy admitted it had initially sidelined or ignored Hollywood’s prominent Jewish founders.”

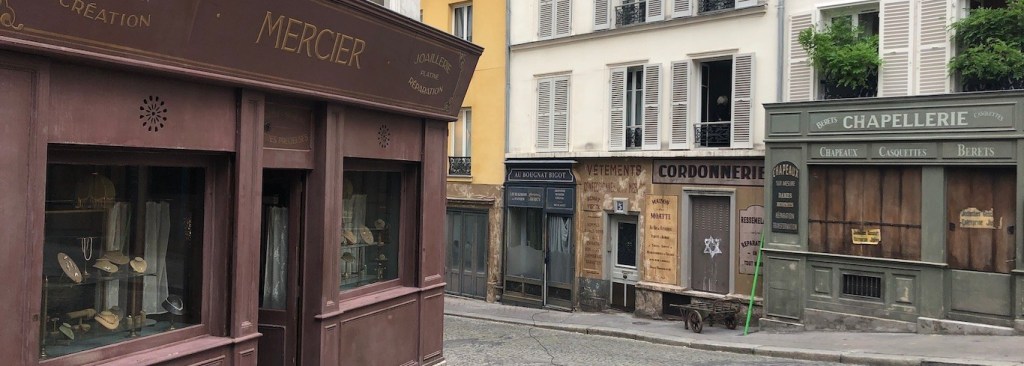

The gallery on the 3rd floor consists of three distinct experiential spaces: 1. A geological model of the L.A. basin with its film studios, 2. a series of wall panels, dedicated to the eight major studios, Fox, MGM, Universal, Warner Brothers, United Artists, RKO, Columbia and Paramount, 3. a screening space presenting a ½ hour documentary, From the Shtetl to the Studio: The Jewish Story of Hollywood, narrated by Ben Mankiewicz, and directed by Dara Jaffe and B.J. Thomas. The film‘s and the exhibition’s master narrative follows that of Neal Gabler’s An Empire of Our Own: How the Jews Invented Hollywood (1989), – Gabler is credited as an advisor – which was hugely influential in naming that which dared not name itself, namely the predilection of the Jewish Hollywood Studio system for self-erasure.

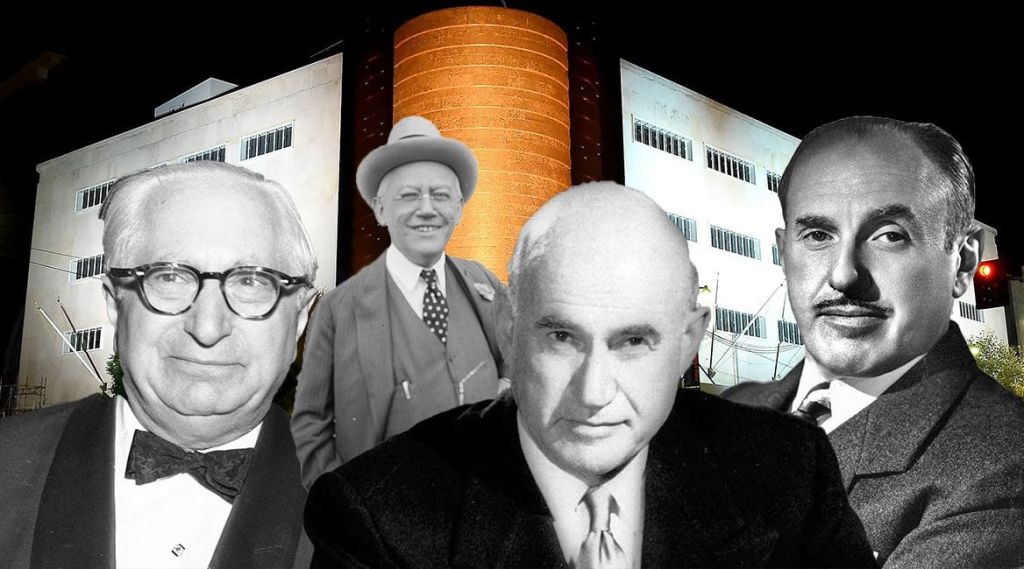

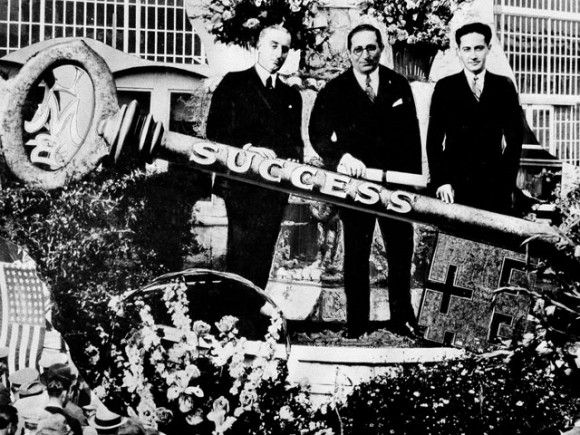

Thus, Eastern European immigrants, often from the garment industry, who were barred by nativist American anti-Semitism from entering many professions or living in a place of their choosing, saw an opportunity to assimilate into the American mainstream by establishing a new entertainment industry through motion pictures. In controlling production, distribution, and exhibition of motion pictures, the major studios headed by William Fox, Louis B. Mayer, Carl Laemmle, Jack L. Warner, Joseph Schenck, David Sarnoff, Harry Cohn, and Adolph Zukor, created a monopoly that not even the government’s anti-Trust units could break for more than 20 years. Despite their power, Jewish producers were gripped by fear of anti-Semitism, not without justification, given attacks from – in chronological order – Edison’s Motion Picture Patents Trust, Joseph Breen and the Catholic Legion of Decency, Henry Ford and America First, and the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). The studio moguls practiced not only public self-effacement in the media, they also produced almost exclusively white nationalist movie dreams for WASP America while actively excluding Jewish Americans, as well as all other people of color from that vision. These were visible merely as stereotypes, as were women and gays. With the demise of the major studios, the Jews “no longer control Hollywood,” the film tells us.

While this narrative is legible in the film, the exhibition’s first space is more impressionistic, offering images of the growth of Los Angeles from a largely uninhabited desert to a thriving metropolis of movies, during which the population increased 12-fold between 1902 and 1929 and movies became its primary business. The wall panels dedicated to the eight major studios follow, offering photographs of the physical studios and stars, film posters, and mini-portraits of their Jewish founders. The film is a thoughtful and easily understood documentary of the rise of Hollywood and its Jewish moguls. Overall, the exhibition is an excellent introduction to classic Hollywood through the 1950s and its Jewish origins, especially for non-specialists, and could easily travel to libraries and other public spaces.

However, given that the Academy’s recent temporary exhibit on African-American in film was five times larger and included numerous original objects, and not just reproductions, one might have hoped for more. Why is the Jewish exhibit ghettoized in a completely separate space, rather than integrated into the narrative flow of other Academy exhibits? Why are there no original objects on view in the museum exhibit from this incredibly rich period of Hollywood history?

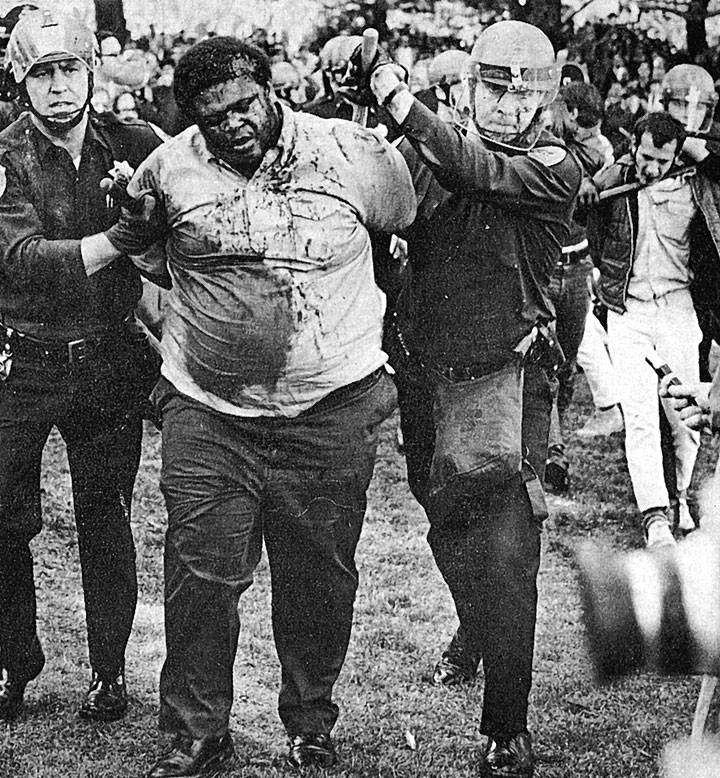

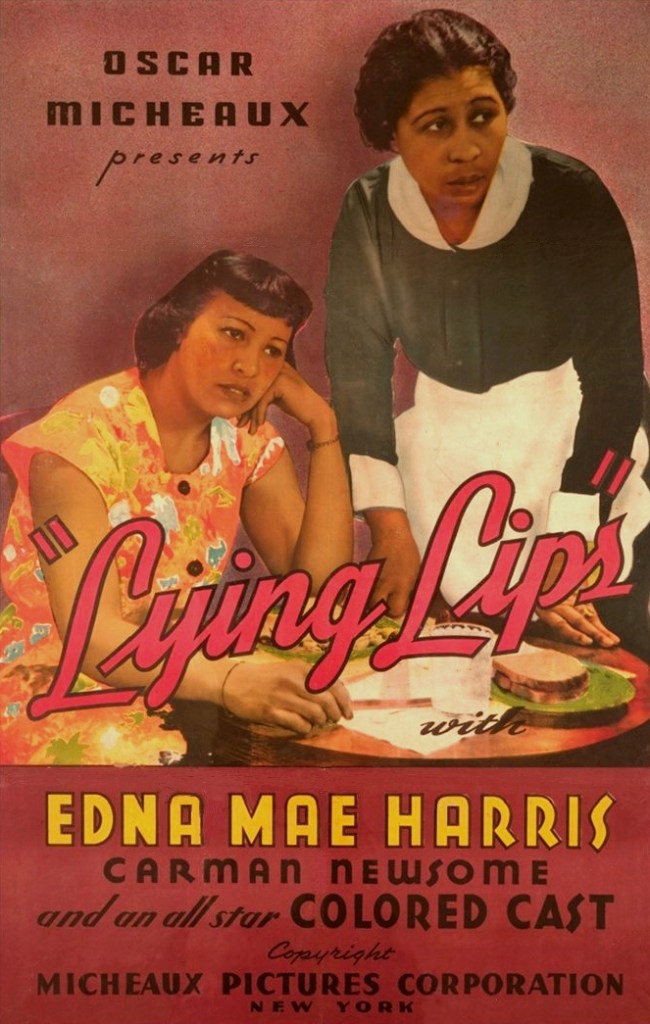

Given the very modest size of the exhibition, there are also missed opportunities to create a more nuanced view, e.g. to talk about Jewish producer-distributors, like Alfred N. Sack and Leo Popkin, who worked with African-American directors like Oscar Micheaux and Spencer Williams to finance race films in the 1930s and 40s, which catered specifically to audiences of color. Jewish filmmakers were also extremely philanthropic, financially supporting numerous liberal causes, including the civil rights movemenmt. Finally, Jewish producers are also credited with bringing over countless European artists to Hollywood, giving their films a cosmopolitan flair, but also rescuing many filmmakers threatened by the racial policies of the Third Reich. Such an exhibit would have however required more space and more generous financing beyond the mea culpa on display.