Archival Spaces 392

Czech Silent Film History

Uploaded 6 February 2026

Back in Summer 2023 (Blog 326), I wrote about a Czech film playing at the San Francisco Silent Film Festival, The Organist at St. Vitus Cathedral (1929), directed by Jan S. Kolár. It is an amazingly atmospheric melodrama, shot mostly in real locations around Prague’s Hradčany Castle, its magnificent Cathedral, and Alchemist’s Alley, as well as other Mala strana locations, the medieval quarter on the left bank of the Vltava River. I’ve now been asked by Dennis Bartok of Crocodile Films to write an essay for a new Blu-ray release of two other Jan Kolár films, including The Arrival From the Darkness (1921) and St. Wenceslaus (1930), as well as a number of shorts. Kolar is not as well-known as other Czech directors, such as Gustav Machatý (Ecstasy, 1932) and Karel Lamač (Saxophone Suzi, 1928), possibly because his directorial career ended with the advent of sound. However, Czech silent cinema in general has been ignored by film historians.

One searches in vain in classic film histories for assessments of Czech cinema of the 1920s, even though Prague’s annual film production had been steadily increasing since 1918-19, reaching admirable figures for such a small country. Neither Georges Sadoul nor Gregor/Patalas discusses Prague cinema. If Czech film is mentioned at all, e.g., by René Jeanne and Charles Ford, it is only in connection with Gustav Machatý, whose two art films, Kreutzer Sonata (1926) and Erotikon (1929), were screened internationally. Paul Rotha wrote that films made in Czechoslovakia were unknown, apart from Machatý’s Ecstasy. Only Jerzy Toeplitz mentions other trends, such as the sentimental comedies of Lamač or the nationalistically tinged biographical films of Svatopuk Innemann, while quoting Czech film historians Karel Smrž, Myrtil Frída, and Jaroslav Brož, all of whom favored the so-called “cosmopolitan direction” of Machatý. The Czech émigré historians Mira and Antonin Liehm confirm the dismissive opinion of some Czech film historians regarding the entire silent film production when they write that, despite the considerable number of Czech film productions, “…the films grew to display increasing provincialism, oriented more and more solely to the domestic viewer’s desire for cheap entertainment and even cheaper nationalism.” Meanwhile, Czech film specialist Peter Hames dedicates only a few lines to Machatý, but at least acknowledges that 1920s film production still needs to be researched.

Part of the problem is that international film historiography only promoted art films, while the emergence of a national culture in commercial cinema was ignored. Yet, with an annual production of approximately 26 to 38 feature films a year, the Czech silent film industry’s output was only slightly exceeded by the Czechoslovak “New Wave” of the 1960s.

It is also important to consider that surviving Czech films present the opportunity to study an entire national film production, which is hardly possible for any other film-producing country. An informal survey shows that 163 feature films from the years 1920 to 1930 still survive, while 101 are lost. Thus, the Czechs have managed to preserve more than 60% of their national production, while approximately 90% of German and American film production from the silent film era has disappeared. This survival rate allows for an analysis of Prague’s film production in a breadth and depth that is unmatched. Today, after Czech cinema achieved worldwide acclaim in the 1960s, after three Czech films won Oscars, and after the domestic film industry has now again been operating under capitalism for 37 years, 20 to 22 feature films are produced annually, accounting for approximately 23% of the films shown in the Czech Republic. Perhaps, therefore, a new historical approach is needed to account for the specific historical circumstances of Prague film production in the 1920s.

Born in 1918 out of the embers of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the first Czechoslovak Republic featured an American-style democratic constitution, a highly industrialized economy, and a strong middle class. In the 1920s, Czech film producers financed a significant number of films, which were directed solely at the domestic market, being produced cheaply enough to forgo foreign sales in their amortization plans. The Czech model of cultural autarchy thus complicates the widely held notion that all national film production needs an export market. A recurring criticism of those Czech films with foreign releases concerned the numerous intertitles, which were characterized as anachronistic. One reviewer, e.g., complained about the “overabundant, conflict-creating, and conflict-resolving titles” in Kreutzer Sonata. However, it must be remembered that before 1918 and the founding of the Republic, all films screened in the Austro-Hungarian Empire had to have German titles or dual-language titles. It can therefore be argued that the overabundance of Czech intertitles played an important role in creating a sense of national, cultural identity and provided pleasure for Czech speakers, previously denied expressions of their own language.

I would therefore like to propose some working hypotheses to stimulate research into Czech silent film, focusing on the national rather than the international, on genre production rather than art films. 1. Czech film producers of the 1920s financed films that recouped their costs in the domestic market, without necessarily focusing on the international market. 2. Commercial genres, such as comedies and melodramas, but also, on a more sophisticated level, film adaptations of Czech literary works and historical films, dominated Prague’s film production. 3. Both comedies, melodramas, and historical films conveyed specifically Czech values that contributed to identity formation. 4. National themes and popular ideas were prioritized to enhance popularity domestically. 5. The survival of a large portion of Czech film production allows for a broad-based content analysis of Czech films, specifically to suss out cultural obsessions.

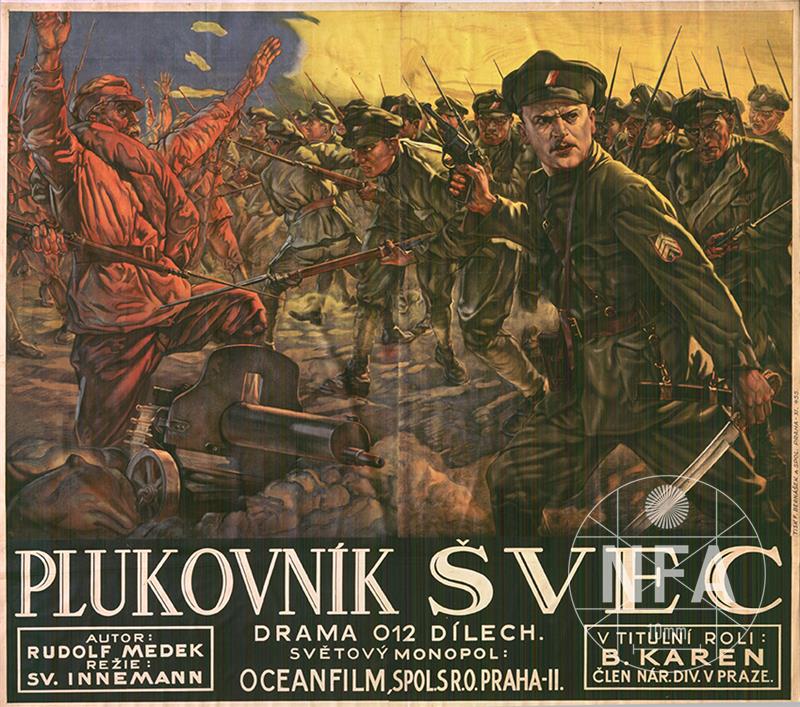

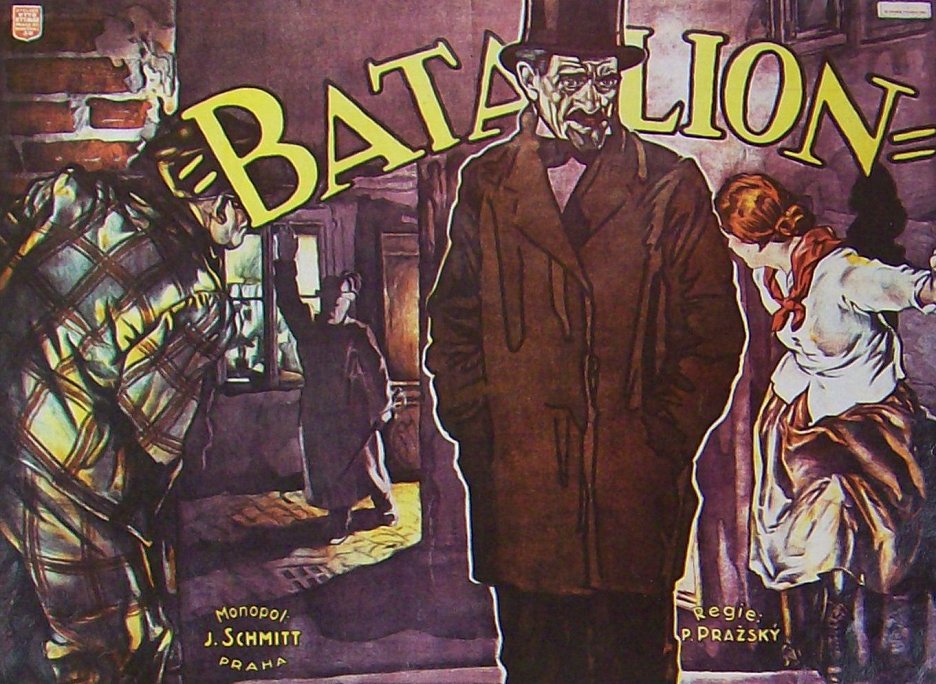

Hopefully, the Blu-ray release of the Kolar films will stimulate interest in further Czech silents, e.g., the films of Thea Červenková (The Grandmother, 1921), Premysl Prazský (Batalion, 1927), Karel Lamač (Sins of a Woman, 1929), Svatopuk Innemann (Colonel Svec, 1930), and Karel Anton (Tonka of the Gallows, 1930), even if these names are unpronounceable for English speakers.

6. The innovative experimental films such as „Aimless Walk“ (1930) and a few more.

LikeLiked by 1 person

yes, very important. Hackenschmid!

LikeLike