Archival Spaces 390

My Short Government Career

Uploaded 9 January 2026

In the Fall of 1987, I received a call from David Paul, a producer at the United States Information Agency, asking if I could compile for them a list of German Academy Award winners. No problem. He followed up with a letter a month later, inviting me to work in East Berlin on a USIA exhibit. Founded in 1953 at the height of the Cold War, USIA was the propaganda arm of the American government. The Agency’s mission, in its own words, was “to understand, inform and influence foreign publics in promotion of the national interest, and to broaden the dialogue between Americans and U.S. institutions, and their counterparts abroad.” Little did I know that my short career at USIA would see the last gasp of Communism in Eastern Europe.

Given the agency’s anti-Communist legacy, I was not keen on working for USIA, but Mr. Paul noted that German Democratic Republic film officials acknowledged “the expertise of Dr. Horak and are in complete agreement” to invite him to East Berlin as a film specialist for a USIA exhibit, “Filmmaking in America.” I felt I couldn’t turn down the Germans, given my long-standing relationship with the film archives of the GDR. I never found out who supported me in East Berlin, but I suspect it was Wolfgang Klaue, the head of the Staatliches Filmarchiv der DDR, to whom I spoke regularly at FIAF conferences. David Paul wanted me to train docents for the exhibit. Furthermore, I was to act as a master of ceremonies for the opening, give lectures, and meet with local film industry people, including a visit to the East Berlin film archives..

After receiving a U.S. government security clearance, I arrived in East Berlin on 31 March, billeted at the Hotel Metropol, a premier “Interhotel” for Western foreigners. The exhibit itself was housed on the ground floor of the East Berlin radio tower on Alexander Square. It was a massive 8,000-square-foot exhibit, consisting of prefabricated panels for easy transportation, with reproductions of photographs, film clips on monitors, and audio recordings that related the history of Hollywood. My contribution specific to the German iteration was the “Hall of Fame,” consisting of photos of prominent Hollywood film people born in Germany. The docents were all American students studying in Berlin who spoke German. After a couple of days of training, we were ready for the gala opening, which was attended by several very high functionaries of the ruling Socialist Unity Party, American Ambassador Francis J. Meehan, and the “state actor” Erwin Geschonneck (Jacob the Liar). But the real surprise was the next morning at the public opening, when literally thousands of East Berliners stood in line around the radio tower, waiting to see this first American exhibit ever in East Germany. The first seven days of the exhibit saw an incredible 30,000 visitors, and eventually brought in 126,000 visitors in 22 days, making it the USIA’s most successful site for that exhibit. And while it was reviewed in Neues Deutschland, the official organ of the Socialist Unity Party, the success was due to word-of-mouth, since it had not been supported in State media, which usually ignored or suppressed news from the West.

Living in East Berlin, without ever going to West Berlin (except for one late night of bar hopping with my docents) was a strange experience. I had spent time in West Berlin for research or at the Berlinale Film Festival, but usually only visited East Berlin briefly to buy books or go to the film library, and never stayed overnight. As an American, I was able to procure a 24-hour visa easily at “Checkpoint Charlie.” On this trip, I had plenty of time to explore other parts of East Berlin, even travelling to the outskirts at Lake Müggel, where I interviewed Rudolf Hirsch, an anti-Nazi writer who, after spending years underground in Nazi Germany and the war years in Palestine, moved to East Berlin in 1949. I gave two lectures at the GDR film school “Konrad Wolf” in Potsdam and the Humboldt University in East Berlin, my topic: German Jewish film émigrés in Hollywood. On the drive to Potsdam, which required an hour-long detour around West Berlin, often driving along ‘the Wall,’ Mr Klaue told me “citizens of the GDR no longer see the Wall,” which surprised me, given how far we had to drive to get around it. The Wall would, in fact, come down 18 months later and along with it the Communist government.

Then, in January 1989, I received a call from David Paul, asking me whether I would organise a seminar in Prague, in connection with the Czech version of “Filmmaking in America.” While the docent training was handled by a colleague, the Czechs stated that the “history and beginnings of the U.S. film industry were quite well-known and therefore suggested an emphasis on contemporary developments,” including a seminar on animation and new independent cinema. My mission was to organise the seminar and visit Czech institutions related to film production. I invited three filmmakers and one critic: Leslie Lee, African-American scriptwriter; Rachel Reichman, independent woman filmmaker; Tanya Weinberger, independent animator; and Don Crafton, film academic and author of an important history of animation. We arrived on Sunday in May, Monday, we had all-day briefings with the American Embassy and our host, Krátký Film. The next day, we staged our seminar, Rachel and Leslie making presentations about their work in American independent cinema, followed by a discussion, where I asked most of the questions, while the audience politely listened. I learned privately that not only had the State-owned Krátký Film done almost no advanced publicity, inviting only selected individuals, but that they were extremely nervous about the topics which might come up. The exhibit itself had been hidden away in an exhibition hall in Letna Park, north of the Moldau.

The second day, dedicated to animation, proceeded much more smoothly, animation being less politically charged. Tanya discussed her computer-generated animated films, which the Czech audience of animators ogled in awe, as if suddenly having a window into the future, given that computer culture in Prague was still in the dark ages. Don’s lecture on the history of American animation, with numerous examples, was received with a different kind of interest because the Czechs had probably never seen them. Over the next few days, we met with a host of other Czech film industry types, having candid discussions and less productive propaganda sessions, sometimes even perceiving schisms in the Czech ranks, with younger hosts openly sympathetic. The Apparatchiks had reason to worry; in less than six months, the Stalinist government would fall.

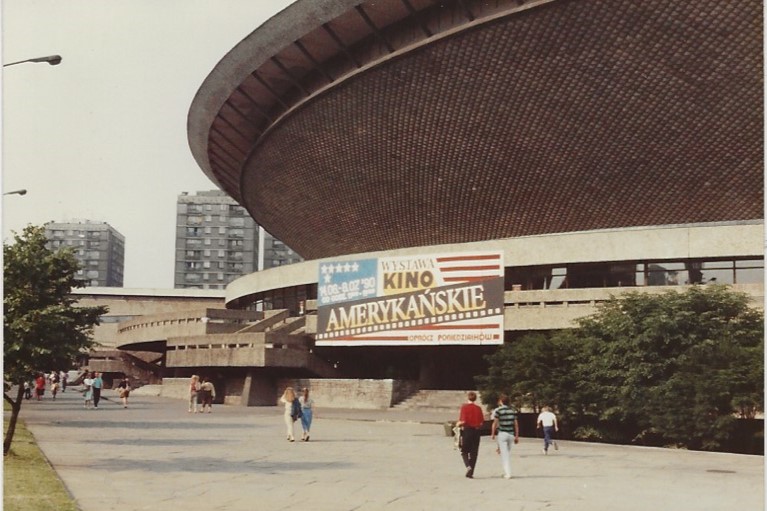

A little more than a year later, my wife and I were in Madrid on vacation when David Paul tracked me down again. His “Filmmaking in America” docent trainer had to cancel days before the Polish iteration opened in Katowice. After getting permission from the George Eastman Museum, I flew to Kraków in June 1990, where a day later, I began training local Polish students. The opening and subsequent interviews with the press went well. The Communists had relinquished power only months earlier, so Poland was a bit like the Wild West, a country in political limbo. Prostitutes formed a gauntlet in my hotel lobby, drugs were easily obtainable. I did have a chauffeur and a car at my disposal. I asked him to drive me to Auschwitz, but that is another story. With the Fall of Communism in Eastern Europe, the USIA’s days were also numbered.

My first Berlinale Film Festival was in 1988. The Wall was still up but several of us wanted to see East Berlin and the Berlin Alexanderplatz we’d seen in Fassbinder’s TV series.

At Checkpoint Charlie the young American soldier did everything he could to turn us back, telling us the East Germans would require us to exchange money we would not be able to sell back upon return. He assured us there was nothing to buy and the food was inedible. But we were not to be deterred.

I could not find cinema shops and didn’t have contacts at the archives. But I did find a shop selling Soviet propaganda posters that were quite stunning and cheap. And in a record store I got a Melodia’s release of “Сно́ва в СССР” by Paul McCartney—that is “Back in the USSR.” I actually got two copies of the LP.

I kept them all but have no memory of lunch.

The Wall came down in November, 1989 and the next time I returned was several years later and Berlin Alexanderplatz was a very different place.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I don’t remember any cinema shops, but there was a large book store on Alexander Place, which sold any book in print in the GDR, including fiilm books.

LikeLike

Hi Chris â great memories~~your were my first art museum curator mentor â the world has changed so much since then â crazy …

Best,

Jane

Jane Milosch, PhD

Honorary Professor and Visiting Professorial Fellow in Provenance and Curatorial Studies

jane.milosch@glasgow.ac.ukjane.milosch@glasgow.ac.uk

Cell +1 202-436-1946

[PastedGraphic-1.png]

LikeLike