Archival Spaces 387:

Otto Krieg’s German Film in the Mirror of the Ufa

Uploaded 28 November 2025

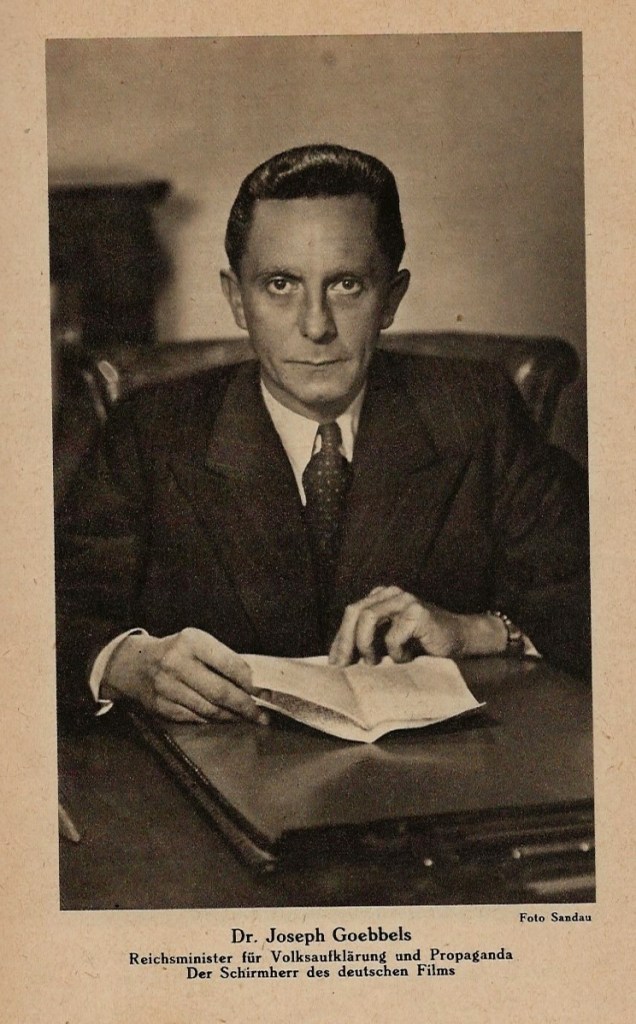

By 1943, the Ufa was not only the largest German film company, as it had been in the Weimar Republic, but the only German film company, nationalized and under direct control of Joseph Goebbels’ Nazi Propaganda Ministry. In celebration of the 25th anniversary of the founding of the Universum Film A.G., Goebbels’ Ministry published two histories of the company: Otto Kriegk’s Der deutsche Film im Spiegel der Ufa / German Film in the Mirror of the Ufa and Hans Traub’s Die UFA – Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte des deutschen Filmschaffens /UFA – A Contribution to the History of German Cinema Art. The latter is – despite its title – a large format (9” x 13’) volume that focuses solely on the economic and structural history of the film industry, with 80 pages of illustrations of cinemas, studios, and cameras, written by a film scholar. Part Jewish, Hans Traub avoids anti-Semitism by eschewing any mention of Jews at all, even omitting the forced removal of Jews from the industry in 1933. Kriegk’s film history, on the other hand, is an openly anti-Semitic work by a journalist long allied with the white Nationalist Right, that blames the (unnamed) Jewish film pioneers for the degeneration of German cinema, at least until it is rescued by Adolf Hitler and the Nazi movement.

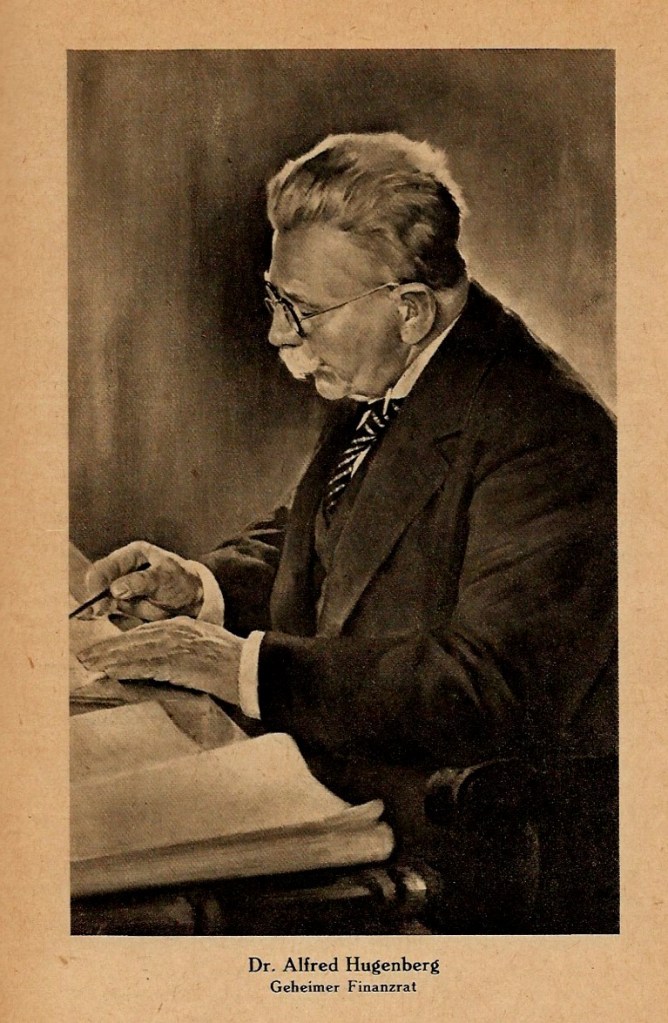

Kriegk’s radical anti-democratic and anti-Semitic credentials were impeccable. Born in a small town in Lower Saxony in 1892, Kriegk earned a PhD. in 1914 in economics at the University of Göttingen with a dissertation on beer production, then became a political editor at a rightwing newspaper in Bremen; during WWI he was kept out of military service, due to blindness in one eye. In 1922, he joined Alfred Hugenberg’s radical nationalist press empire, becoming a close associate of Hugenberg’s, writing an official biography, and working as press chief for Gen. Paul von Hindenberg’s successful presidential campaign in 1925, the first step in the upending of German democracy. As co-editor of Der Deutschen-Spiegel, Kriegk advocated that the radical Right take the presidency and weaken democracy from within, rather than through (unsuccessful) putsches, like Kapp and Hitler’s Beerhall. Over the next twelve years, he published numerous right-wing political tracts, railing against Jewish domination in international relations and attacking in particular the Locarno Peace Treaty (1925), while continuing his journalistic work for Hugenberg’s Scherl newspaper chain. He joined the Nazi Party in 1937 and soon became Goebbels’ favorite journalist. In 1944, he was one of only two journalists allowed to attend the Volksgerichtshof trial of the 20 July conspiracy against Hitler, then writing the official Nazi press release about the failed assassination plot.

Kriegk’s book, which carries the subtitle “25 Years of Struggle and Achievement,” begins with full-page portraits of a Nazi rogues gallery, including Fritz Hippler, the director of The Eternal Jew (1940), and the late Emil Georg von Stauß, the founder with Gen. Ludendorff of the Ufa in 1917. The narrative begins with a personal romanticized narrative of discovering Henny Porten, Asta Nielsen, and Paul Wegener in the cinema, then relates the founding of Ufa by the German High Command in 1917, before going on the attack against “the Jews from the garment district” (p. 81), producing pornographic films, after the end of censorship in November 1918. When censorship was reestablished in May 1920, “the Jews who had made their money with cinematic bordellos, withdrew into their basement hovels.” (p. 82) Kriegk reduces the postwar Weimar era to Hollywood’s attempts to destroy German cinema independence, mentioning successful imports to America, Madame Dubarry (1919) and Dr. Caligari (sic)(1920), without naming their Jewish film directors. Then comes Metropolis: “The attempt to beat American films with a film produced in Germany, led straight to a glorification of Bolshevism.”(p. 91-2) Thus, Kriegk, as in all his previous political writings, connects Jews with the threat of Communism and sexual degeneracy. Hollywood’s initial victory over UFA and the Berlin film industry was complete with the Parufamet contract of 1925. Further help, according to Kriegk, was given by the Jewish Berlin publishing houses of Mosse and Ullstein, which were allegedly allied with American banks.

In 1927, the Hugenberg Group came to Ufa’s rescue, installing Ludwig Klitsch as Chairman of Ufa’s Board, infusing massive amounts of capital, and sending Klitsch to New York to renegotiate the Parufamet contract. Meanwhile, sound films had arrived. America forced Germany to show The Singing Fool, starring “der Neger Al Johnson” (sic). The Ufa fought back with state-of-the-art sound film studios, defended itself against a successful sound film patent war, but then the Depression hit. According to Kriegk, liberating German cinema from Jewish influence was not possible through private means alone, given that 70% of film production in 1932 was in Jewish hands. Those Jewish interests, allied with left-wing critics, continuously attacked the Ufa. The Blue Angel (1930) and The Congress Dances (1931) are identified as successful German counterattacks, but fail to mention that both films were produced by Jewish film crews. Indeed, contradictions and illogical conclusions abound.

After the Nazis took power, the goal was to purge the industry of Jews and eliminate (Jewish) “industry business practices” (p.183) whose goal was speculation, rather than uplifting German culture. Kriegk quotes a 1935 Goebbels speech extensively, listing proscriptive formulas for German cinema, then sings the praises of such Ufa films, as Hitlerjunge Quex (1933), while attacking an unnamed American gangster film for including “everything a Jewish political dictatorship needs to stupefy the masses”(p. 224), as well as “bolshevist” Russian films. Ironically, while dedicating space to Ufa’s successful nationalist productions, including new color films – Jew Süß is only mentioned once in a list of other titles – Kriegk literally spills considerably more ink on the Moscow-New York-Hollywood Jewish conspiracy to destroy German cinema, maybe because he is unable to discuss their dubious aesthetic merits. If you want to know about Ufa’s real history, read the late Klaus Kreimeier’s excellent The Ufa Story (1999).