382: Abraham Ravett

Archival Spaces 382: Abraham Ravett Films in Berlin

Uploaded 19 September 2025

I’ve known independent filmmaker Abraham Ravett for 35 years. We met when he came to Rochester in 1990 to screen his late Hampshire College colleague, Tom Joslin’s Blackstar: Autobiography of a Close Friend (1976), one of the first films about everyday gay life. Abraham and I became friends and have kept in touch over the years, our friendship cemented by the fact that we are both sons of concentration camp survivors, whose fathers were silent. Recently, Abraham wrote to me that his films be screened in Berlin, a selection of four experimental films he has made over the years, ostensibly about his family, and the family he might have had, were it not for the Holocaust. The films will screen on 30 September at the Zeughauskino in the German Historical Museum on Unter den Linden Strasse.

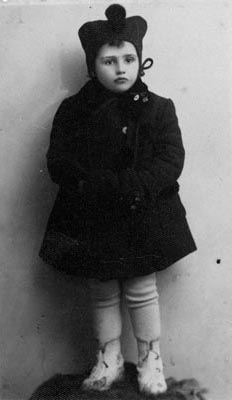

There is a mysterious image of young girls carrying chairs over their heads, obscuring their faces, that is repeated several times in Abraham Ravett’s Half Sister (1985), a shot we learn at the film’s end was taken by a Nazi cameraman in the Warsaw ghetto. Like a second image from the same source of girls exiting a door, possibly a school, it is a stand-in for Ravett’s half-sister, Toncia, who perished in the Holocaust. Abraham’s mom describes the moment her daughter was taken from her in May 1944, one of a few sound sequences in the film. But like the other films in the program, Half Sister is about absence, loss, and silence. We see modern footage of a woman at various stages in her life, implying the life Toncia may have led, but also a field burning, symbolizing the chimneys at Auschwitz. Most of the images, whether negative, out-of-focus, or flash frames, do not reveal their meaning; they are too disconnected to create coherence, just as the loss of a child and a would-be sister defies comprehension.

Łódź:22592 explores the Jewish ghetto in what the Germans called Litzmannstadt in the years 1941-1944, as captured by the Jewish photographer, Henryk Ross (1910-1991). Ross, who worked for the Nazis but was Jewish, buried the negatives in 1944, then recovered ca. 3,000 of them after the war. The collection was eventually purchased by the Art Gallery of Ontario, which published the book, Memory Unearthed. The Łódź Ghetto Photographs of Henryk Ross (2015). Ravett begins the film by placing a copy of the catalogue on a table, and then reproducing images from the book, while noting in a title, he wishes he could see images of his father, first wife, and their two children. The film is thus a search for traces of his family in their last known place of residence. It is a film about the trauma of loss, of fragments of memory and images which will never again create a whole. Ravett utilizes long takes to explore Ross’s black and white photographs of everyday ghetto life under Nazi occupation, children, street scenes, work in factories, family gatherings, the subjects often looking directly into the camera. Ravett also intercuts images of ghetto postage stamps and other public documents. The film is almost completely silent, except for snippets of ambient sound and a color image of Łódź today, its past invisible. There follows a live action shot of Abraham’s father later in life, talking but without sound. As I know from Abraham, Ravett’s father never revealed the secrets of his Holocaust survival; the end title tells us the film is dedicated to ר׆׆ חװק (Chaim Rawet). One image shows a portrait of a Jewish woman with the negative number 22592 clearly visible. Ravett highlights the number in his title. Could this be an image of his father’s first wife, who perished in the Holocaust? The film’s silence indicates that neither the filmmaker nor we shall ever know.

Ravett’s obsessive (and seemingly futile) search for his father story is given abstract form in Notes for a Polish Jew (2012), an experimental film, created with an optical printer. The silent film opens with a freeze frame of a typical Communist era food shop in Łódź, then a brief image of a man walking through the frame who could be Abraham’s dad, but is not, because as he tells us in a description of the film “If his father had lived beyond the age of seventy-four, the following may have been the cinematic response to the city….” But the image is fleeting, the footage abstracted by slippages in the projector, flash frames, black and colored leader, scratches, sprocket holes, upside down footage, discolored frames, a Goofy cartoon. Shot in color in the 1980s, we see glimpses of ordinary Poles and an open air marketplace, but they reveal nothing of the present or the terrible past. The film ends as it begins with a man walking throught he frame, a circular narrative into a void.

If Łódź:22592 revisits the filmmaker’s relationship to his father, One flower (2023) is a recent film about his mother, who has been the subject of numerous previous films, including The March (1999), Lunch with Fela (2005), and Trepches (2009). At its center is a grainy photograph of a women, her head and face obscured by decomposition, the only photo his mother managed to carry from Poland to Israel and then to America. We never learn who is seen, but we read that, like Abraham’s father, her mother had a family that perished in the Holocaust. Ravett obsessively asks questions he can’t answer. Maybe that is the real message of the Holocaust. Silences dominate the film, just as the fragments of images and documents, whether a large family portrait with grandmother, grandfather and mom, passports of his parents, Abraham’s youthful sketches of his parents, unidentified images of black & white country landscapes, . children in a kibbutz or grocery lists, raise more questions than they answer. But asking those questions is itself an act of mourning and memorialization.

P.S. The Zeughaus Cinema has moved temporarily into the Pei-Bau on Hinter dem Glasshaus 3, just off Unter den Linden.