Archival Spaces 378:

The Irish Film Company’s Knocknagow (1918)

Uploaded 25 July 2025

The San Francisco Film Preservel presented an online lecture by Veronica Johnson on 18 July about the still little-known Film Company of Ireland (1916-1920), focusing on the company’s feature, Knocknagow (1918). An Irish film historian, Dr. Johnson, is following up on work done by Steven Donovan, Kevin Rockett, Maryanne Felter et al., who published a special issue on the Film Company of Ireland (FCOI) in the Australian online film journal, Screening the Past (http://www.screeningthepast.com/issue-33/). Listening to the talk, I had to think about Liam O’Leary (1910-1992), a good friend of my mentor George Pratt, whom I had the privilege of interviewing at the Paris FIAF Congress in 1988. His book, The Silent Cinema (1970) was on my bookshelf next to Pratt’s Spellbound in Darkness. O’Leary was a huge advocate of an Irish National Film Archive, which was finally established in the year of O’Leary’s death and now holds his huge collection of Irish film history material.

The Film Company of Ireland was founded by Henry Fitzgibbon, Ellen “Nell” O’Mara Sullivan, and James Mark Sullivan in March 1916. The couple had married in 1910, before the Irish-American returned to America, where he was involved in Democratic politics. After he had a brief diplomatic career as U.S. Ambassador in San Domingo, the Sullivans moved to Dublin in 1915. FCOI developed an association with the well-known Abbey Theatre in Dublin and was able to hire actors Fred O’Donovan and J.M. Kerrigan. By the end of 1916, FCOI had released nine short comedies. O’Neil of the Glen was a realistic drama and the only film that has survived; others were destroyed during the Easter Uprising of 1916; the majority were directed by J.A. Kerrigan, who would have a substantial career in Hollywood after 1923. In 1917, the Company produced seven more films, some of them multi-reel dramas, before going bankrupt at year’s end. It was at that point that Nell Sullivan, whose family had means, purchased FCOI.

Knocknagow (1918) was FCOI’s first major feature, based on the most popular Irish novel of the 19th century, Charles J. Kickham’s 1873 Knocknagow. Novel and film visualize in very realistic detail the plight of Irish farmers, already hammered by the potato famine of mid-century, who are now being evicted from their land to make way for large cattle ranches, even though the aristocratic English landlord is shown in a positive light in the film, while his evil land agent creates havoc. Like the novel, there are no overt political references to the Iris Rebellion, but land tenancy and forced emigration are important issues.

Shot on location in County Kerry, on Ireland’s southwest coast, the film premiered on 30 January 1918 in Clonmel, County Tipperary, then toured the country before commencing a one-week run in Dublin on 22 April 1918. Meanwhile, the Sullivans had left for America, where they hoped to distribute the film to large Irish-American audiences. Pathé showed an initial interest, but then demurred, possibly because of the film’s two-hour-plus length. The film was screened at the Fremont Temple in Boston, where it was viewed by Irish Cardinal William Henry O’Connell, and discussions were held with the Schuberts, but the film never received any distribution in America and thus proved to be a financial disaster. Nell Sullivan, who held the copyright to the film and was uncredited as the scriptwriter, died in May 1919, most probably during the Spanish Flu Epidemic, as did one of her children. Her husband, James, though reported in the American press as having died, returned to America with his surviving children and lived until 1935 in Florida. Meanwhile, the Film Company of Ireland completed two more now lost films, before its final demise in 1920

In making Knocknagow, the Sullivans wanted to produce a more realistic view of Ireland than had been circulated in popular culture. As James Sullivan noted in an interview before leaving for America, “We desire to show Ireland sympathetically; to get away from the clay pipe and the knee breeches; to show Ireland’s rural life, with pride in the same; to show Ireland’s metropolitan life intelligently, depicting the men and women of the 20th century—in short, Ireland at its best in every walk of human endeavor.” (Evening Herald, 13 April 1918)

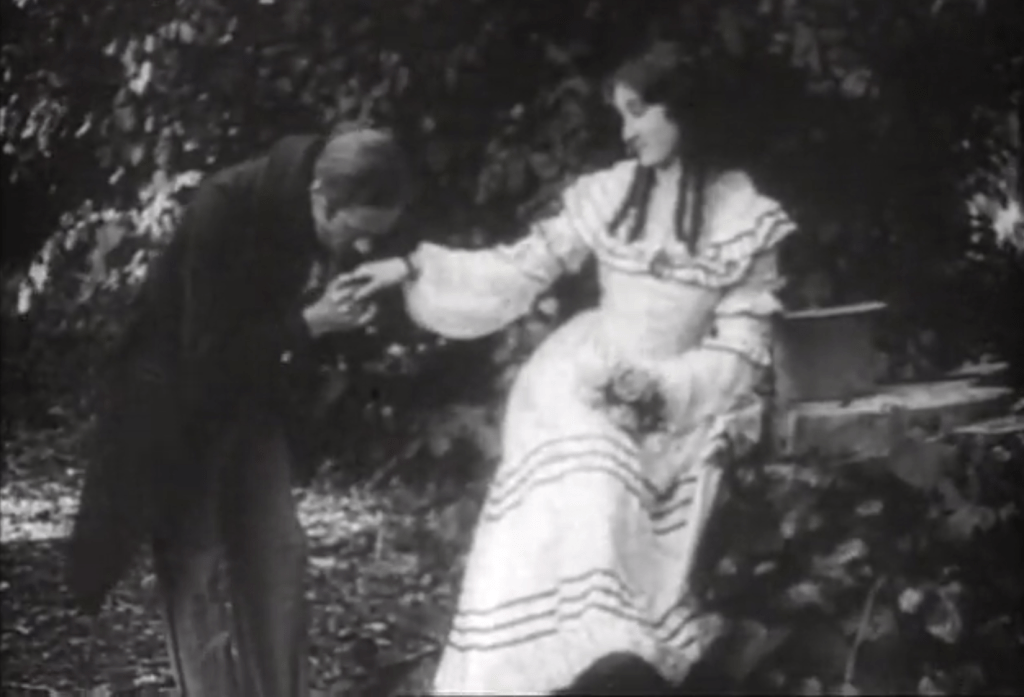

Knocknagow was restored in 2012 by the British Film Institute and is available on the Internet Archive in an 80-minute version. In the first forty minutes, the plot meanders a bit, but then the land agent Pender begins the evictions, throwing farmers off the land and burning their homes. Several love dramas between various couples ensue, with Mat Donovan, the nominal hero, leaving for America because he believes Bessie Morris loves another. Pender conspires to have Mat falsely arrested for stealing the collected rents while boarding a ship in Liverpool, although it is actually Pender who has purloined the funds. Donovan is eventually released, and Pender is arrested, allowing the farmer to search for Bessie in America before returning to Ireland with his bride. Given the epic scope of the novel, the film reveals narrative gaps, and many scenes are relatively static long shots, but Knocknagow remains an interesting document of Irish nationalism.

Thanks Chris for posting this. I can’t remember studying anything about Irish cinema in Barrett’s film history class. Just the 5 Five:American, French, German , Italian, and Russian/ Soviet.

Regarding evictions of farm households to make way for cattle(and sheep?)grazings: I recall one of the ways used to motivate recalcitrant farmers to leave was setting their homes on fire.

LikeLike

Indeed, Irish cinema has not been on the map of world cinema, although we have famous American filmmakers, like John Ford who were Irish.

LikeLike

Thanks Chris for posting this. I can’t remember studying anything about Irish cinema in Barrett’s film history class. Just the 5 Five:American, French, German , Italian, and Russian/ Soviet.

Regarding evictions of farm households to make way for cattle(and sheep?)grazings: I recall one of the ways used to motivate recalcitrant farmers to leave was setting their homes on fire.

LikeLike

Really intriguing article about another subject I know so little about! I had a question concerning the tumult in 1916: You mentioned that several Irish silent films were destroyed due to the Easter Rising of 1916; were these works destroyed because they had the bad luck of being stored in one of the locations the Irish Republicans were occupying (& were subsequently besieged), or as part of the reprisals by the English afterwards?

LikeLike

From what I gather, the offices of the Film Co. of Ireland were destroyed during the Easter 1916 Uprising and with it the film negatives.

LikeLike