Archival Spaces 377:

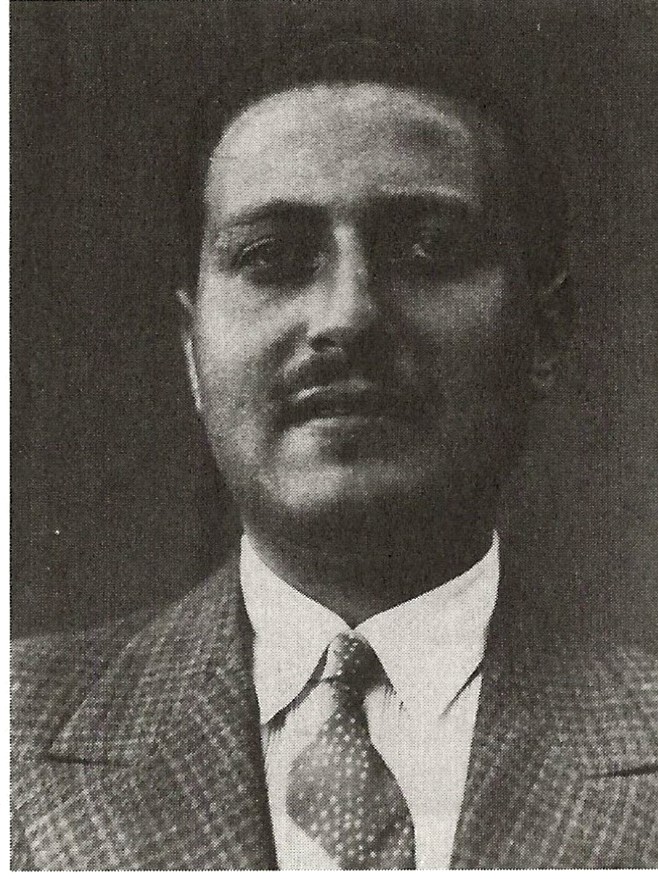

Hans Feld, Weimar Film Journalist

Uploaded 11 July 2025

Hans Feld is probably the most well-known and prolific film journalist writing for Weimar Germany’s most widely read film industry publication, Film-Kurier, after Lotte Eisner. Hans Feld was born on 14 July 1902 in Berlin and died on the same day, his 90th birthday, in 1992 in London. A complete bibliography of all his reviews and articles, Hans Feld: Redakteur und Kulturjournalist. Bibliografie Film-Kurier 1926-1932 (Munich: Text + Kritik), edited by Eva Orbanz, formerly of the German Kinemathek in Berlin, has been available for a couple of years. Unfortunately, bibliographies are the stepchild of film studies, despite their centrality to film historical and archive research, which leads me to this blog on the eve of Hans Feld’s birth/death date.

I first met Hans Feld briefly in October 1981, when we were both contributing authors to the catalogue Prussia in the Cinema, part of a major exhibition, organized by the German Kinemathek. In August 1982, I interviewed him on the phone and corresponded with him about the photographer/filmmaker Helmar Lerski. At the time, I was researching Lerski for an exhibition and was trying to track down his then still lost film, Avodah (1934), which had been screened in London in 1938. I had found Feld’s review of Avodah in a Zionist newspaper, published in Prague. Ironically, the film turned up more than a decade later in the same West End London cinema where it was originally screened and is now preserved. Feld also told me about Lerski’s failed attempts to work for John Grierson’s documentary film unit. I next met Feld in February 1983 at the Berlinale Retrospective, “Six Actors in Exile,” while I was writing my dissertation on anti-Nazi films by German-Jewish emigres; I interviewed him, as well as Alfred Zeisler, Wolfgang Zilzer and his wife Lotte Palfi, both of whom had appeared in Casablanca. After that, I continued my correspondence with Feld to track down some of his former colleagues who had emigrated to England, like producer Max Schach. Feld was no longer in the film business, but he knew a lot of people.

Born into the house of German-Jewish merchant, Herrmann and Hermine Feld, Hans experienced literature and theatre at an early age, thanks to his mother. During the German Revolution in November 1918, Feld joined his high school’s revolutionary council, remaining sympathetic to the Left throughout his life. He studied law, completing a dissertation on “Ministerial Responsibility as the Basis of Modern Democracy ” in 1924. Beginning in 1926, Feld contributed as a freelancer to Film-Kurier, then became editor, and finally editor-in-chief (in 1928). In 1927, he recruited Lotte Eisner to write about film for the journal. According to Eva Orbanz: “He wrote for people, wanted to help them engage, sensitized them to democracy. He understood the cinema to be an art of the masses, railed against its propagandistic misuse. According to Feld, film was to concern itself with questions of the day and take a stand in politics.” He documented German film production and was particularly interested in avant-garde and Soviet cinema. His acquaintances included Sergei Eisenstein, Conrad Veidt, Erich Pommer, and Carl Mayer. As early as 1931, Feld was being put under pressure by his Nazi-leaning boss, Ernst Jaeger. As Sergei Eisenstein wrote to Feld in a September 1931 letter, quoted by Werner Sudendorf in his obituary for Feld in Film Exil, referring to the growing Nazi power: “It’s film worthy, what we are reading about what is happening in Germany today.”

In April 1932, Feld left the Film-Kurier and joined the Aafa Film Co. as production manager, but his tenure was cut short by Hitler. He initially emigrated to Prague, where he founded a cultural journal, but also published in other German exile newspapers and participated in Czech film productions, like the German version of Tatra Romance. In 1935, he, his wife Käti, and young son Michael moved on to London, where he worked for John Grierson, briefly editing World Film News. Two years later, he started a food import business, but remained active in Jewish affairs. With renewed German interest in Weimar cinema in the 1970s, he became an important film historical resource for a young generation of film scholars, including me, recording a long interview with Werner Sudendorf and Hans-Michael Bock in 1981. The same year, he received a German Film Prize from the Federal government.

The importance of bibliographies for film historical research cannot be underestimated, even if some believe internet search engines have made them obsolete. One of my film historical bibles before the internet was The Film Index: A Bibliography; Vol. 1, the Film as Art, published in 1941 by the Museum of Modern Art, which is still useful for finding pre-WWII articles. Digitized sites, like “Lantern. The Media History and Digital Library have helped. But, in fact, trade and academic film periodicals, whether in English or other languages, remain for the most part invisible, still necessitating cumbersome searches, page by page through non-digitized microfilm, as I had to do recently with the Film-Kurier to research Alfred Zeisler. Hans Feld. Bibliografie Film-Kurier begins with Eva Orbanz’s introduction, followed by a selection of 25 essays/reviews, including reviews of Gance’s Napoleon, Brecht’s play “A Man is a Man,” Siodmak’s People on Sunday, G.W. Pabst’s Westfront 1918 and Nikolai Ekk’s Soviet film, Road to Life, which became a major bone of contention between Jaeger and Feld due to its positive tone. The next 500 pages detail every review, report, and notice Feld published in Film-Kurier, listing issue numbers, film credits when applicable, and short descriptions of the texts. The descriptions often supply film historical information that is nowhere else to be found, in particular, about unrealized film projects or contemporary scandals. Indeed, this is a treasure trove of information about Weimar cinema.