Archival Spaces 374:

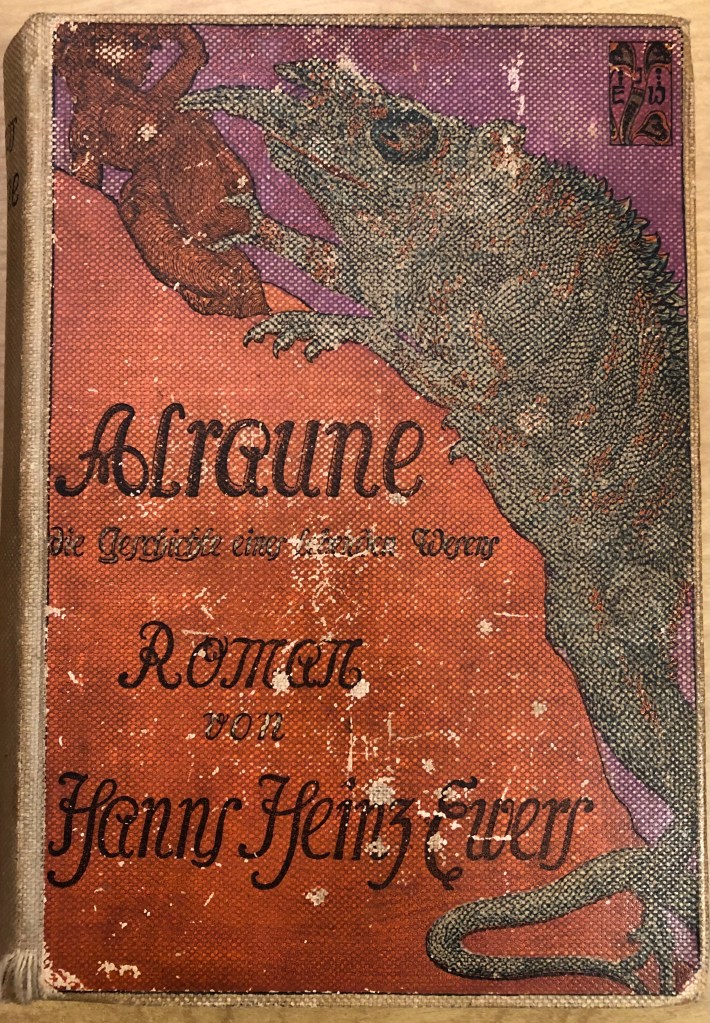

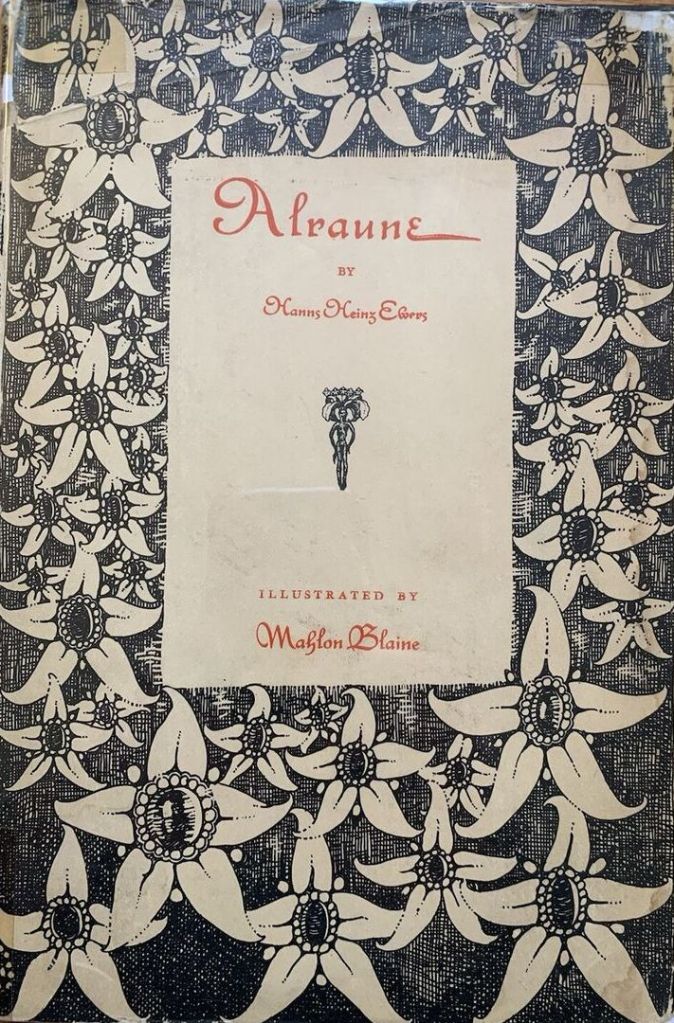

Hanns Heinz Ewers Novel, Alraune (1911)

Uploaded 30 May 2025

A couple of months ago, I recorded a Blu-ray commentary for the 1927 German horror film, Alraune, directed by Henryk Galeen, and distributed in America as Daughter of Destiny. The Blu-ray will be released by Deaf Crocodile around Halloween. The script by Galeen was adapted from the eponymous novel by Hanns Heinz Ewers from 1911. It became an immediate best seller in Germany and remained one for decades, although an English translation was not published until 1929 (New York: John Day Co.) and was long out of print. It was Ewers’ second novel in a trilogy around the character of Frank Braun.

In Alraune, Braun collaborates with Professor Jakob ten Brinken in creating a female homunculus by impregnating a prostitute with the semen from an executed murderer. Being interested in genetics, the Professor uses artificial insemination, then adopts the girl. The resulting young woman is without morals, commits numerous monstrous acts, and drives hosts of men to their ruin. The novel is much more perverse, even anarchistic and anti-capitalist, than the subsequent film versions. Unlike the Galeen film, which begins with a hanging and the retelling of the mandrake (Alraune) legend, the novel opens in the home of the lawyer Gontram, whose youngest child, Wölfchen, will later fall victim to the young woman. Both Countess Wolkonski, who finances the experiment, and ten Brinken are introduced there, but it is Frank Braun who suggests Brinken attempt artificial insemination of a human, while the Gontrams give ten Brinken an unwanted mandrake root. Braun revels in his role as the procurer of the prostitute who will become Alraune’s mother, the next several chapters devoted to the search for a suitable harlot, finding Alma Raune, a woman of unbridled lust. However, Ewers also makes clear she is a victim who is criminally manipulated by ten Brinken and exploited by a social structure that views her and the hanged man as trash.

The girl Alraune goes to a convent school where she teaches the other children how to mutilate and kill small animals, then to a girls’ academy for the well-to-do, expelled from both. She returns home to ten Brinken’s mansion, where she begins driving various men to their deaths, including the family chauffeur, two other rival lovers, and Wölfchen Gontram, who has grown up with little Alraune. When ten Brinken is to be arrested for molesting a young female child, Alraune refuses to flee abroad with him, so he hangs himself, leaving his ill-gained financial empire in ruins. But he names Alraune his sole heir and Frank Braun, who has been completely absent from the narrative, Alraune’s guardian. When Countess Wolkonski’s daughter, Olga, pleads with Alraune to give up her protected status to save her mother’s fortune, she refuses, driving Olga insane. In retaliation, the Countess Wolkonski reveals to Alraune the secret of her birth. Frank Braun, against his better judgment, begins an amour fou with Alraune, while Frieda Gontram, who had been Olga’s best friend, also falls under Alraune’s spell. Braun can’t tear himself away from the seductress, although he manages to burn the Mandrake that Alraune had nailed to the headboard of her bed. Soon after, Alraune and Frieda climb to the roof of the ten Brinken mansion in the moonlight and fall to their deaths in a double suicide.

The structure of the novel is that of the author’s twelve letters to his sister, with additional sections of florid flights of fancy, seemingly divorced from the narrative. The prose is for modern German readers quite archaic, but the most shocking aspect of the novel, given its publication date, is its description of sexual behavior. Alraune herself is consistently described as tender and slight, her body resembling that of a beautiful boy with tiny breasts, who drives both men and women to distraction. One particularly long scene, after which Wölfchen Gontram dies of pneumonia, describes how the pair switch gender roles at a masked ball. Alraune is dressed as a boy in the guise of the Chevalier de Maupin, a character from a 19th-century French novel by Théophile Gautier, while Wöflchen is in drag as Richard Strauss’s Roselinde, his angelic face previously being described as feminine. Frank Baum’s fatal attraction to Alraune, it is implied, is because her body is that of a slender boy, making her attractive to the sexually indeterminate Braun. Then, there is the issue of incest, because ten Brinken also becomes hopelessly infatuated with his adopted daughter, in particular her slim, boy-like body. The relationship between ten Brinken and his young nephew, Frank Braun, may also be incestuous, given the professor’s violent feelings of betrayal. Some of Ewers’ earlier writings had been deemed pornographic by the courts.

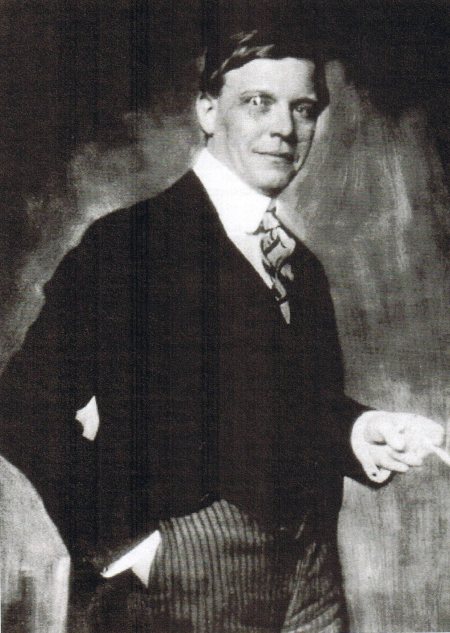

Ewers was influenced by the ideas of the conservative eugenics movement, which defined modernity as an illness leading to degeneracy. Ewers himself belonged to the radical right with anarchist tendencies. Born in 1871 in Düsseldorf, Ewers began writing poetry at the age of 17. After completing his Abitur in March 1891, he volunteered for the military but was dismissed due to myopia. Ewers’ literary career began in 1901 with a volume of satiric verse. His first novel in the Braun trilogy, The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, was published in 1909. A world traveler, Ewers was in South America at the beginning of World War I, relocating to New York City. There, he continued to write and publish, advocating to keep the United States from joining the war as an ally of Britain and becoming embroiled in the “Stegler Affair,” involving German agents. After the U.S. joined the war, he was arrested as an “active propagandist,” but never formally charged. He was sent to the internment camp at Fort Oglethorpe, Georgia, and in 1921 released and deported to Germany. During the last years of the Weimar Republic, Ewers became involved with the Nazi Party, attracted by its nationalism, its Nietzschean moral philosophy, its initial anti-capitalism, and its cult of Teutonic culture, joining the NSDAP in 1931 with Hitler present at the ceremony. However, he did not agree with the Party’s anti-Semitism. His virulent anti-capitalism and his homosexuality soon upended his support with Nazi party leaders, especially after the Roehm Putsch in June 1934. The same year, most of his works were banned, and his assets and property were seized. After submitting many petitions, Ewers eventually secured the rescission of the ban. Ewers died in Berlin from tuberculosis in 1943. His books are mostly forgotten, although a newly translated edition of Alraune by Joe Bandel was published in 2011. Ewers is today only remembered for the three German film adaptations of Alraune and his script for The Student of Prague (1913).