Archival Spaces 373:

American Biograph Co. 68mm Films Added to UNESCO Register

Uploaded 16 May 2025

A month ago, the British Film Institute, London, and Holland’s Eye Filmmuseum, Amsterdam, announced in a joint press release that their unique collection of 300 68mm films from the American Mutoscope and Biograph Company had been added to UNESCO’s International Memory of the World Register. In total, 341 68mm Biograph films are known to exist, with smaller collections from the Museum of Modern Art (36 titles), New York, and the Centre national du cinéma et de l’image animée (5 titles), Paris. The wide-screen format from the turn of the last century was officially protected during the 221st session of UNESCO’s Executive Board meeting between 2 – 17 April 2025 in Paris. The films join previous collections added to UNESCO’s Memory of the World Register in 2011: the Jean Desmet Collection of early cinema from the Eye Filmmuseum, the Mitchell & Kenyon Collection (See Archival Spaces 363) and the General Post Office Collection from the BFI, as well as the silent films of Alfred Hitchcock, which were inscribed on the UNESCO UK Memory of the World Register in 2012.

In the earliest days of cinema, there were several successful competitors to the 35mm format. Founded in 1895 by William Kennedy-Laurie Dickson, who had worked for Thomas Edison, inventing both 35mm film and the Kinetoscope, the American Mutoscope and Biograph Company patented a new 68mm format. Terry Ramseye claimed it was to circumvent Edison’s 35mm patents, but Paul Spehr has maintained Dickson believed image quality was at stake. Requiring significantly larger Biograph projectors, which were in competition with Thomas Edison’s Vitascope and the Lumiére Brother’s Cinematograph, 68mm films were produced for both big screen projection and viewing in Mutoscopes. The 68mm format was four times larger than 35mm, with an image area of 2 by 2+1⁄2 inches (51 mm × 64 mm), projected at 32 fps, resulting in an extraordinarily sharp image, without the flicker and jumpiness of its competitors, and is comparable to today’s IMAX format.

While the Biograph camera punched in perforations in the 68mm negative in order to keep the frame in registration, 68mm prints lacked lateral perforations; instead, projectors used a continuously moving friction feed device (mutilated rubber rollers), that had to be watched constantly in projection, lest the frame line creep south. Like 35mm full aperture frames, the 68mm format had a 1.33:1 aspect ratio. The 68mm Mutoscope negatives were also used to produce paper-based images in a flip card system for the company’s Mutoscope peep-hole machines, which had begun competing with Edison’s Kinetoscope in 1897. The American Mustoscope and Biograph Company actually enjoyed a degree of success for several years with both projection and parlor machines, and only discontinued production of films in 1903.

Now digitized, these marvelous sights are accessible on the Eye Filmmuseum’s website and on YouTube. Stream The Brilliant Biograph: Earliest Moving Images of Europe | Eye Film Player.

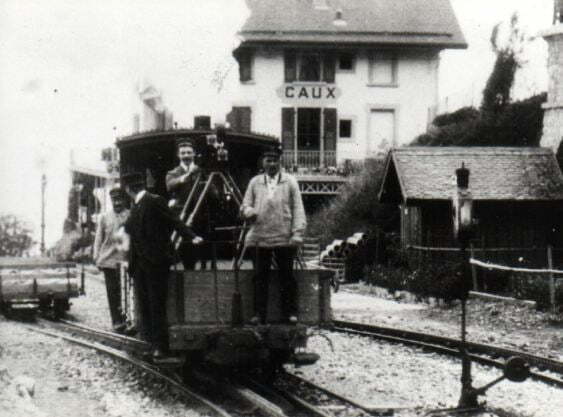

The primary attraction of moving images in the days before even stationary cinemas had been founded was the visual pleasure of seeing the world move, seeing everyday life in faraway places, so Biograph’s cameramen travelled the world. Among the most popular films were images filmed from moving trains, with exotic landscapes rushing by, or, as in Irish Mail (1898), a steam locomotive’s speed captured by a cameraman riding on a parallel track, rushing through train stations, until the faster train passes out of frame. Conway Castle (1900) on Wales’ northern coast is even seen in hand-tinted images, the train passing through the castle’s walls. Other moving camera scenes filmed from boats depict the waterfront in Venice and its gondolas (1899), the Prinsengracht canal in Amsterdam (1899), and British Naval warships on the high seas.

What we would now term anthropological scenes were also popular, depicting images of daily life, like an encampment of Roma (1898), the women cooking over open fires, while the men pose for the camera, or Dickson and his family in Venice’s St. Mark’s Square, feeding pidgeons, while his toddler runs in and out of frame. There are also memorable events, e.g., a funeral in Rome (1898), the casket of the departed and the mourners shrouded in black hoods, or a London fire brigade leaving the station (1899), a very popular motif memorialized later in Porter’s Life of an American Fireman (1902). Other scenes reveal Hungarian peasants drinking at a pub, Italian peasants dancing the tarantella, or Dutch children from the Island of Marken at play. Given the large format and also the conventions of the time, close-ups were non-existent, although on occasion the camera will be close enough to reveal details on faces, as in a scene of a procession of Capuchin monks in the Vatican.

In one remarkable scene, advertising a new Martini rear-engine automobile (1903), we see the car driving towards the camera across railroad tracks, then the cameraman and his camera on a flatbed, followed by another shot of the vehicle driving in a rail bed through the Swiss mountains. This kind of self-reflexivity, displaying both the image and the means of production, was rare, but not unique, e.g. Interior New York Subway (1905, Biograph), which I wrote about in my essay on Bill Morrison’s Outerborough (2005), reworks another 68mm Biograph, New York to Brooklyn Across Brooklyn Bridge (1899). Finally, while there are no views of the Biograph projector in action, there is a scene of audiences leaving a Biograph projection at the Carré Circus in Amsterdam (1899).

It seems miraculous to look into the living and breathing world of 125 years ago, as if it were an image from today.

Hi Chris,

i had no idea this large format (68mm) had been tried.

Great scholarship!

LikeLike

Particularly interesting blog, Chris. I learned a lot from it; thanks.

-Marty Cooper

Sent from my iPhone

LikeLike