Archival Spaces 368

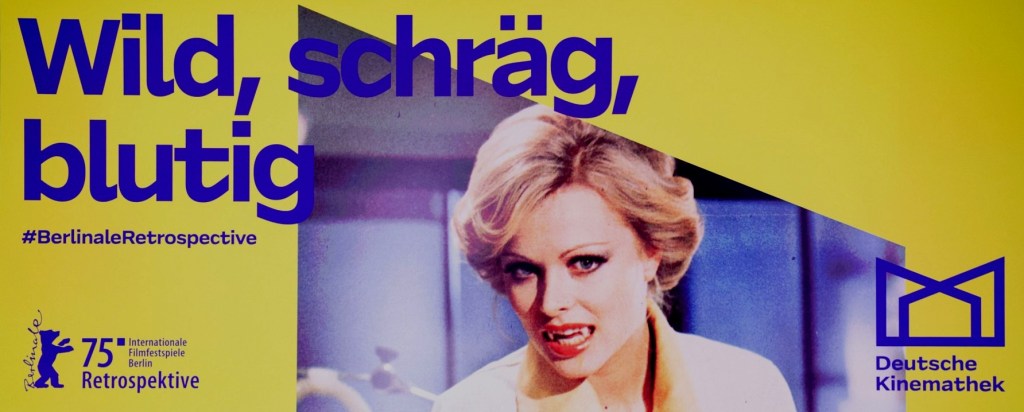

Retro: German Genre Films from the 1970s

7 March 2025

Hard to believe that it was 51 years ago that I attended my first Berlinale film screening. I actually wasn’t in town that Summer of 1974 for the Festival but rather to research my master’s thesis (Ernst Lubitsch) at the Deutsche Kinemathek, which was then still located on the Theodor-Heuss-Platz. Thanks to the Kinemathek’s Walter Seidler, I got to see R.W. Fassbinder’s Effie Briest and also experienced a press conference with Fassbinder. Since then, I have attended about half of all subsequent Festivals, including 2025, where my focus – though not exclusively – was on the Retrospective curated the last 19 years by Kinemathek Director, Dr. Rainer Rother. Given his retirement, the Berlinale honored him during the Festival with the prestigious Berlin Camera Award.

This year’s retro, “Wild, Weird, Bloody. German Genre Films of the 70’s,” included films from both East and West Germany: crime, horror, musicals, melodramas, not New German (art) Cinema. Unfortunately, I missed some films I was dying to see, including The Tenderness of Wolves (1973, Ulli Lommel), The Girls from Atlantis (1970, Eckhardt Schmidt), and Spare Parts (1979, Rainer Erler). The first two films I caught up with were musicals from the German Democratic Republic; indeed the East Germans were represented exclusively by musicals and a comedy, since horror and crime were considered decadent, exploitive capitalist genres, – sci-fi and westerns were made, but as anti-capitalist Lehrstücke – while musicals were a concession to popular tastes, fuelled by the almost universal availability of West German television.

The DEFA musical, Hat Off When You Kiss (1971, Rolf Losansky), features a war between the sexes fought on the relationship level between lovers: He is a boring petit bourgeois engineer who can’t stand the fact that she is an auto mechanic and loves her work. In revolt, she pretends to be interested in a swarmy Argentine industrialist while both visit the Leipzig Trade Fair, allowing the producers to show off wares from the East Block Comecon. The film ends with a truce of sorts, but Hat Off reveals the extent to which East German men were unhappy about their spouses working, even though the State propagated gender equality and actually needed women to work.

Don’t Cheat, Darling (1973, Joachim Hasler) starts out visually like a West German musical in a small Bavarian town, but when Young Pioneers join the parade, it’s clear this is East of the Elbe. The town is crazy about Fussball, engendering a town-wide war between the sexes, led by a new girl’s technical college director and the town mayor. Hardly a Communist in sight, only certain termini technici reveal the film’s location, as male footballers and nubile female students face off in energetically choreographed dance numbers.

An exceedingly weird operetta adaption of Jacques Offenbach’s Orpheus in the Underworld (1973, Horst Bonnet) constituted the third GDR contribution. It opens with Offenbach setting off from 19th century Paris to Greece in a hot air balloon, where he witnesses Euridice being seduced by Pluto and taken to Hades, while husband Orpheus is glad to be rid of her so he can sleep around. Offenbach (and public opinion) force Orpheus to the underworld to rescue Euridice; meanwhile, Juno is on Jupiter’s case because she thinks he seduced Euridice. While the gods are stand-ins for the capitalist ruling classes, both Olympus– all in white – and Hades in black seem to be hotbeds of libertinism, with naked breasts front and center, the film ending in chaos and cancans, like the operetta.

Finally, the screwball comedy Carnations in Aspic (1976, Günther Reisch) is a pretty wild critique of the East German economy’s total dysfunctionality, although the film sates that the events depicted could only happen in film and have NOTHING to do with contemporary GDR reality. A commercial designer in the State advertising agency loses some front teeth through his own stupidity, forcing him to remain silent during office meetings, whereupon he is promoted up the food chain because his bosses think he always agrees with them. He actually just wants to get the girl, not the work responsibility, so he tries to screw- up, but that only brings him more promotions. Meanwhile, we get slogans like: “If you buy a Wartburg, it will be delivered in time for your son to drive,” a bitter comment on the 10-15 year delivery times for East German cars.

Cynicism characterizes the three West German films I viewed. Strange City (1970, Rudolf Thome) opens like a film noir in b & w with a well-dressed 30-something – 70s German heartthrob Roger Fritz – arriving in Munich at night with a suitcase full of cash. He finds his estranged wife and wants her to launder the money he has stolen from the Düsseldorf bank, but a dogged Munich cop and another couple are on his tail. A crime, but no violence, just lots of maneuvering to possess the booty. In the end, two crooked cops and the two couples split the loot, all happily riding off into the sunset, proving crime does pay.

Bloody Friday (1972, Rolf Olsen), a German-Italian co-production, takes violence and blood-letting to the extreme, in keeping with Giallo genre aesthetics. A violent criminal escapes from custody, organizing a bank robbery with two accomplices in a suburban Munich bank that includes taking hostages to guarantee their getaway, after stealing weapons from a U.S. Army transport. The bearded gang leader kills indiscriminately, drinks on the job and rapes a hostage he accuses of being a lesbian. Meanwhile, the police are under massive pressure because one of the hostages is the daughter of a rich industrialist. In the end, the robbers either shoot each other or are gunned down by the police when they hole up in a deserted Bavarian tavern.

Deadlock (1970, Roland Klick) opens with a wounded man carrying a suitcase full of cash through the desert, while Can’s avant-garde Krautrock blares on the soundtrack, mocking Ennio Morricone; the hero faints just before an old pickup rumbles into the scene, its decrepent occupant taking the bank robber to an abandoned mining town. When the robber’s accomplice shows up, an extended and deadly cat-and-mouse game ensues between the three men to make off with the cash, ending with the death of two (innocent) women and two men. An anti-Western of stasis rather than action, however, without a carefully set-up final duel.

This year’s Berlinale retrospective proved once again that European genre films are still mostly terra incognita for American film scholars, despite the many pleasures to be found here.