Archival Spaces 366:

Marta Eggerth’s First Film

Uploaded 7 February 2025

The independent film producer/director Richard Eichberg produced his films up to early 1928 at UFA’s Babelsberg Studios, then moved his base of operation to London’s Elstree Studios and British International Pictures, although he also continued to produce films in Berlin. In 1930, Eichberg hired the Hungarian coloratura soprano, Marta Eggerth, in her first sound film, Die Bräutigamswitwe/The Groom’s Widow (1931), after she had starred in a part-talkie in Budapest earlier that year. By that time, the 18-year-old had already sung on some of the major opera stages of Europe, including in Max Reinhardt’s 1929 staging of Die Fledermaus. Although identified in the credits as a “sound film farce,” The Groom’s Widow includes at least four musical numbers, while the film musical features anarchic comedy, a mixture of genres, and a discontinuous cabaret-style plot, similar to contemporary UFA musicals. Eggerth’s film career would take off in Berlin, which continued – even though she was Jewish – after Hitler’s rise, before emigrating to Hollywood with her singing partner, Jan Kiepura.

After getting wildly drunk at his own bachelor party, rich playboy George Brown (George Alexander) wakes up with a hangover and a bride, Fay Miller (Marta Eggerth), – she’s a chorus girl – even though he is to be married that morning to his upper-class fiancé, Maud (Gertrude Kohlmann). To make matters worse, Fay’s burley fiancé, Bill Huber (Fritz Kampers) shows up to give George a thrashing. Both supposedly die in the tussle that follows. At the inquest, Fay and Maude then argue over who is really the groom’s widow. George and Bill turn up alive separately, each worried they have murdered the other, leading to a cat and mouse game, engineered by Fay who knows the truth, before all is resolved and George realizes he loves his little chorus girl. This is after all aimed at the American market, where the English Version, Let’s Love and Laugh, opened before playing in the U.K, where it was produced.

All four musical numbers, written by Hans May with lyrics by Jean Gilbert, feature Eggerth’s operatic voice, in particular in Eggerth and Kohlmann’s dueling duet, “The Groom’s Widow,” where each claims to be the true heir. The film seemingly begins in a classroom, where the students sing “ABC, Love doesn’t hurt,” the number morphing into a cabaret stage when the students tear off their frocks to dance; a final chorus /curtain call reprises the opening Schlager, “My Heart is a Salon for Beautiful Women.” The film’s broad comedy involves not only a war between the romantic leads, but also the intrusion of Fay’s uncouth, petit bourgeois parents, who immediately move into George’s mansion, featuring a stiff and anal-retentive butler, and a police detective who solves crimes through séances, a parody of Dr. Mabuse. Mashed into the discontinuous action are other genres: George and Bill believe they are seeing ghosts, a parody of ghost/horror films; when George’s valuables are stolen from his safe because Fay gets distracted, Fay is falsely accused, the plot briefly turns into a Hitchcokian crime drama; not surprising, given that scriptwriter Walter Mycroft, wrote Hitchcock’s Murder (1930), and co-scriptwriter Frederick J. Jackson started his career at Lubin in 1915.

One of Eggerth’s favorite composers, Hans May, wrote songs for five Eggerth films before he and lyricist Jean Gilbert were forced into exile in 1933; cameraman Heinrich Gärtner and scriptwriter Károly Nóti also fled the Nazis. Despite the Propaganda Ministry’s ideological prohibitions against “Jewish” film operettas, Marta Eggert continued starring in no less than twelve musicals (not counting seven English, Italian, and French versions); surprisingly, but typical for crass Nazi opportunism, many of the films were financed by Jewish producers from Austria. They were distributed throughout the Reich, in the rest of Europe, and in South America. The actress’s blonde curls, her Hungarian star image, and the fact that the Reich needed the hard currency certainly impacted Goebbels’ decision to approve Eggerth’s films. Hungarian actresses, like Eggerth (and before 1933 Gitta Alpar), but also so-called “Aryans,” like Marika Rökk, Hilde von Stolz, and Käthe von Nagy, gave Nazi cinema an international flair, thus normalcy, when out in the street life was anything but normal for Jews and non-white people.

Operetta composer Franz Lehar’s work was also banned by Goebbels, however, the composer received special dispensation to write Eggerth’s Der Zarewitsch (1933, Viktor Jansen), The Whole World Revolves Around Love (1935, Viktor Tourjansky) and Where the Lark Sings (1936, Karel Lamac). Martha Eggerths subsequent films in the Third Reich (until she left in 1938) mixed musicals with other genres, including Douglas Sirk’s The Court Concert (1936.

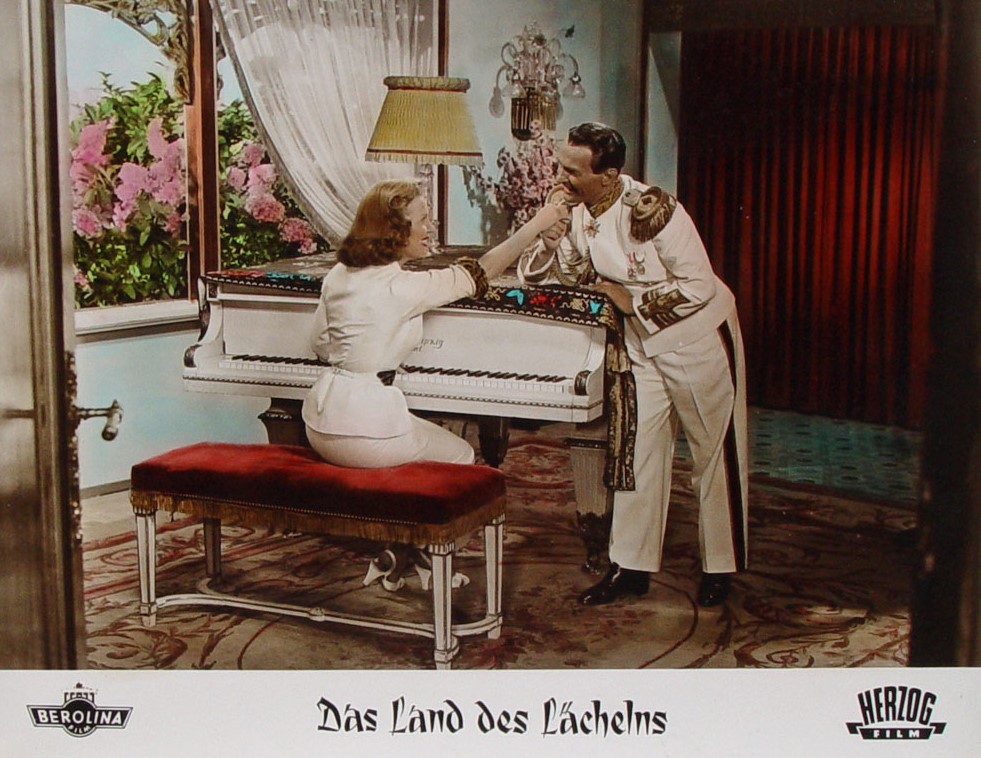

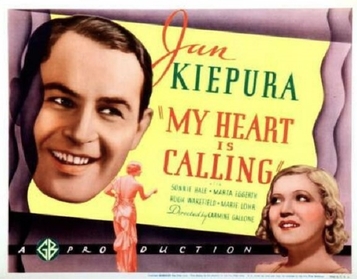

It was on the set of My Heart is Calling You (1934, Carmine Gallone) that Eggerth met and fell in love with the Polish operatic tenor, Jan Kiepura. They married in 1936. When he received a contract to the New York Met, Eggerth moved to New York, where she continued her stage career. During the war she appeared in only two films, both Judy Garland musicals, which she personally hated, no longer the star. After the war, she and Kiepura starred in three European filmed operettas, including The Land of Smiles (1952), but maintained their New York residence until Marta died at 101 years in 2013.