Archival Spaces 356

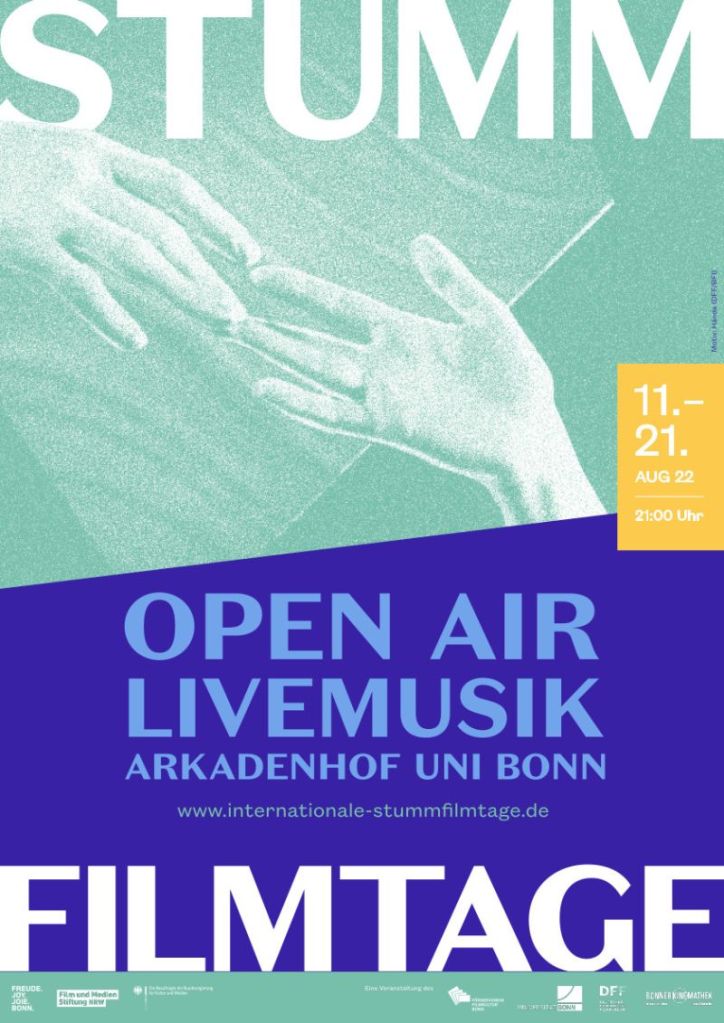

Bonn Silent Film Festival

Uploaded 20 September 2024

The 40th iteration of the Bonn International Silent Film Festival took place from 8 – 18 August 2024. Over eleven Summer evenings, the open-air festival screened twenty-two silent features and shorts from eleven countries, always accompanied by live musical performances. As in the past few years, the festival under the curatorship of Eva Hielscher and Oliver Hanley is also streaming about half the program, which has greatly increased the reach and fame of the festival. Ten films were available for 48 hours online, beginning 10 August.

Streaming began with Du skal ære din hustru/Master of the House (1925), Carl Theodore Dreyer’s feminist Kammerspiel screened in an excellent print/file with a beautiful score by Sabrina Zimmermann and Mark Pogolski. Strangely, Bonn’s program notes downplay the film’s status in the Dreyer oeuvre, saying it “cannot be considered a great film,” even though many film historians now rank it among Dreyer’s silent masterpieces. Confined almost exclusively to a small lower middle class flat, the film portrays an authoritarian pater familias who treats his wife and children as personal slaves. With the help of an old nanny, wonderfully played by Mathilde Nielsen, the husband is knocked off his high horse, while the wife escapes to a much-needed rest in the countryside. Dreyer’s actors walk a fine line between comedy and melodrama, while George Schnéevoigt’s documentary camera roves through the flat, capturing minute details and the mise en scene tracks the shifting power relations within the family. Like La Passion de Jeanne d”Arc and later Dreyer films, Master of the House exploits the formal device of confined spaces to invariably entrap its subject.

Teinosuke Kinugasa, best known for his Oscar-winning color film, Gate of Hell (1953), directed Jûjiro/Crossways (1928), two years after his expressionist masterpiece, A Page of Madness (1926). Like the latter film, Kinugusa employs expressionist techniques and a complete catalog of cinematic tricks to portray the fever dream-like madness of Yoshiwara, the red-light district of ancient Tokyo, where a brother and sister attempt to survive in squalor. The brother falls prey to a l’amour fou with the district’s most famous courtesan, is temporarily blinded by a rival, forcing his sister into prostitution to raise money for his recovery, all for naught. Kinugasa’s sympathies lie with his poor protagonists, surrounded by the false glitter of Yoshiwara’s non-stop carnival. Kinugusa stages the red-light district as just another kind of insane asylum, with the queen of the prostitutes and her minions laughing hysterically through much of the film.

I had previously seen the Czech film, The Organist at St. Vitus Cathedral (1929) at the San Francisco Silent Film Festival, but it was worth a second look. Both film noir and atmospheric melodrama, shot mostly in real locations around Prague’s Hradčany Castle, its magnificent Cathedral, and Alchemist’s Alley. The film concerns an aging organist and a nun who leaves the order, brought together by her father’s suicide in the organist’s tiny home, complicated by a neighbor’s blackmail scheme. Martin Frič privileges spaces with floor and ceiling visible, i.e. realism, yet mixes in expressionistic imagery to communicate emotional content, and despite heading towards tragedy, offers an over-determined American style happy ending that almost seems parody in its excess.

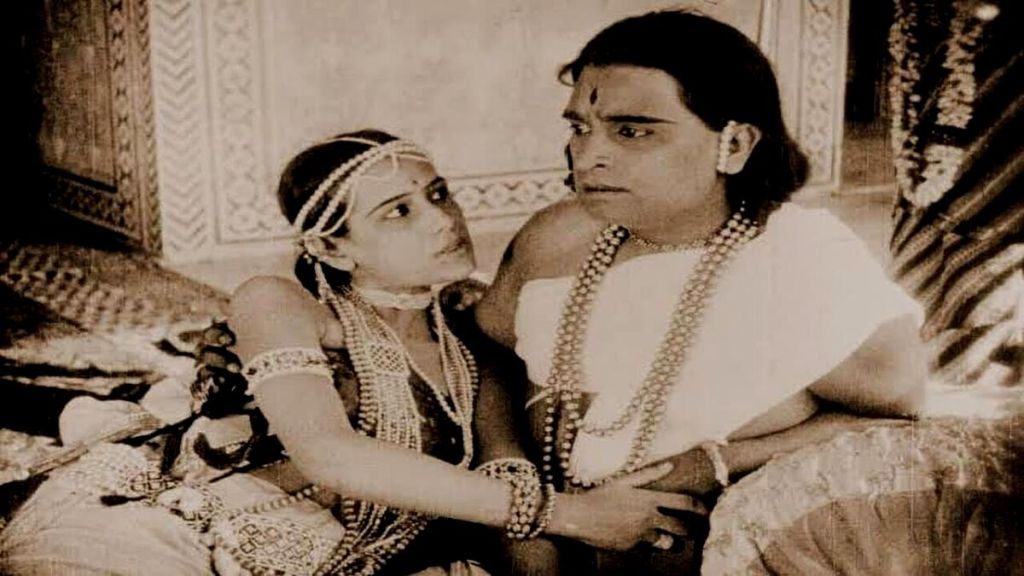

In 1924 the Bavarian film director, Franz Osten, the brother of Emelka Studios founder Peter Ostermeyer, traveled to India to shoot The Light of Asia (1925), a filmed biography of the founder of Buddhism, co-financed by the Indian actor Himansu Rai, who also played the starring role. Shot exclusively on location in India, the film presents both an extended tourist view of India and its ancient monuments, as well as the story of Siddhartha, based on the epic poem by Edwin Arnold (1879) and Hermann Hesse’s eponymous novella, published in Germany in 1925. The first two-thirds of the narrative illustrate the Buddha’s growing disenchantment with the material world (he is a prince), while in the final third, we see his wife Gopa (Seeta Devi) search for him, as he casts off all signs of wealth to become a beggar and teacher. Apart from the sumptuous images, the film’s amazing score of Indian music by Willy Schwarz and Riccardo Castagnola made the film an unforgettable experience.

Karl Grune’s Eifersucht/Jealousy (1925) moves from the lower middle-class expressionist milieu of Grune’s Die Strasse (1925) to the drawing rooms of the wealthy, where a marriage (Werner Krauss, Lya de Putti) is sorely tested by bouts of jealousy. Except for a street lamp scene, and the husband’s subjective view of his wife dancing with a stranger in a crowded ballroom, expressionism has been replaced here by Neue Sachlichkeit, sumptuous décors and UFA-studio designed cityscapes that seem influenced by Lubitsch’s and DeMille’s social comedies, however, without the irony. Produced by Erich Pommer, Jealousy‘s privileged milieu is in keeping with Weimar’s economic recovery after the Dawes Plan and the end of inflation. The film’s happy end, despite a near murder, reflects briefly both New Realism’s and the German Republic’s optimism about the future.

The Swedish film, Thora van Deken (1920, John W. Brunius) begins seemingly with an inheritance swindle, when a corrupt lawyer and estate manager dupe a wealthy landowner to change his will on his death bed in their favor, but morphs then into a melodrama involving a widow’s perjury, when she claims falsely to have destroyed her husband’s last will, to secure her daughter’s inheritance. Pauline Brunius as the protective mother gives an amazingly nuanced performance, caught between her allegiance to her daughter and her sense of morality. Unfortunately, in trying to capture the expansive novel by Henrik Pontoppidan, the director inserts too many flashbacks, complicating the narrative flow. Nevertheless, the film reveals many of the atmospheric qualities of Seastom and Stiller.

The Portuguese Maria do mar (1930, José Leitão de Barros) is an avant-garde film from the political right, experimenting with film technology, down to the Vertovian climactic chase to save a child, but embodying conservative cultural values. It also freely mixes film genres. Part documentary about the hard life of fishermen, made a year after John Grierson’s Drifters, part ethnographic film in its documentation of village dances and funerals, part melodramatic Romeo and Juliet story with a little situation comedy to lighten things up, given that the central drama concerns a blood feud between two mothers, begun when a fisherman drowns and his wife blames the boat’s skipper. Utilizing amateur actors, the film’s performances are more than credible, visualizing the viciousness of the ancient village gossips, ending in two old women beating each other up on the street.

The international scope and aesthetic quality of Bonn’s silent film program is exceptional, as are the musical performances by such musical stars as Maude Nielsen, Stephen Horne, and Neil Brand.