Archival Spaces 354

Prelude to World War II: Documentaries

Uploaded 23 August 2024

In the Summer of 1938 my dad, Jerome V. Horak, was mobilized into the Czechoslovak Army and received rudimentary basic training when it looked like an invasion by Nazi Germany was imminent. Less than a month later, he was sent home, after Neville “Peace in Our Time” Chamberlain, the British Prime Minister, stabbed the Czechs in the back by caving into Adolf Hitler’s demands to annex the so-called Sudentenland, border areas in Czechoslovakia with large German-speaking populations, despite a defensive alliance with the Czechs. On 1 October 1938, the Wehrmacht marched in without a single shot fired, the Central European nation losing its mountainous natural border, making any resistance futile. Somehow, my dad managed to finish his matura, only to be arrested in his freshman year at Prague’s Technical University by the Gestapo. Obviously, I had to think about my dad watching a new Blu-ray release by Flicker Alley, “Against the Storm,” which features two films, Crisis: A Film of “The Nazi Way” (1939) and Lights Out in Europe (1940) that together document the political developments in Czechoslovakia and Poland/England as they nervously prepared (or didn’t) for a war against German Fascism.

Herbert Kline, an American journalist affiliated with the Communist Party, had gone to Spain to fight in the Spanish Civil War for the Republican side, where he collaborated on two documentaries, Heart of Spain (1937) and Return to Life (1938). After Hitler’s so-called “Anschluß” of Austria in March 1938, which left tiny Czechoslovakia almost completely surrounded by the Third Reich, an invasion seemed imminent. Kline and his wife Rosa Harvan traveled to Prague, where they joined forces with Alexander Hackenschmied and Hans Burger to capture the crisis mood in that fateful Summer. of ’38. All three would share writing and directing credits while Hackenschmied, who had produced avant-garde and advertising films in Prague and would later shorten his name in America to Hammid, marrying Maya Deren, also acted as cinematographer, and co-editor. Burger, a German-speaking Czech Jew, also functioned as a producer, before emigrating to America, then returned to Germany with the U.S. Army to co-direct with Billy Wilder, the first film shot in a concentration camp, Death Mills (1945).

Shortly after the premiere of Crisis on 11 March 1939 in New York, days before the Nazis occupied what remained of the Czechoslovak Republic, Kline and Hammid traveled to Poland and Great Britain, where they filmed the prelude and aftermath of Nazi Germany’s invasion of Poland on 1 September 1939. That film, Lights Out in Europe, premiered in New York on 13 April 1940. Both films were distributed by art house specialists Arthur L. Mayer and Joseph Burstyn, and greeted with ecstatic reviews, according to Thomas Doherty, the author of the accompanying booklet, but ironically, the left-wing press was less keen, accusing the filmmakers of giving too much screen time to the Nazis. Indeed, the two films, which Kline considered to be two parts of the same film, convey a sense of unease, apprehension, and danger, which were hardly the stuff of uplifting Communist agitprop.

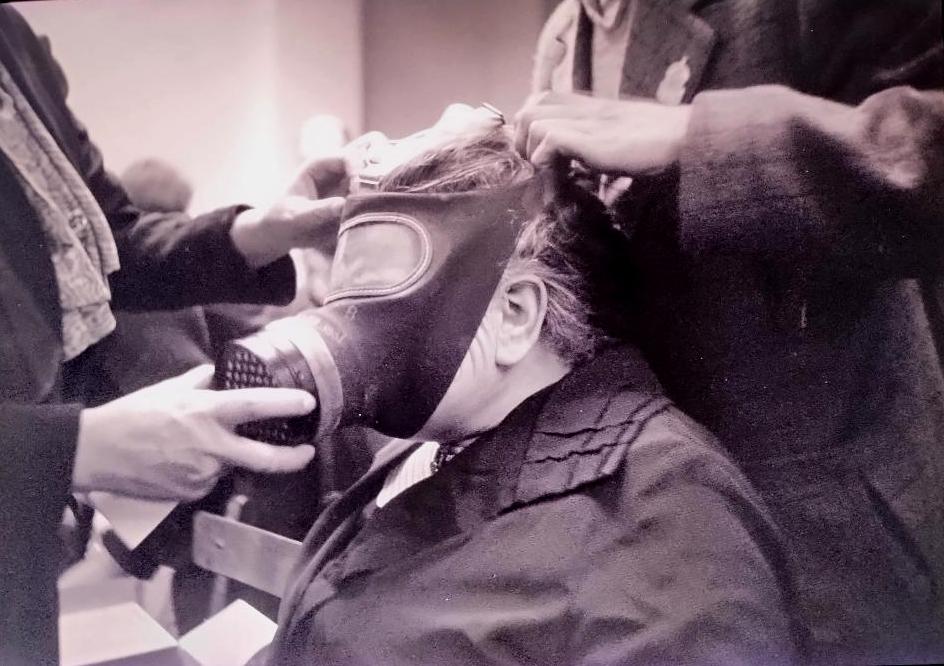

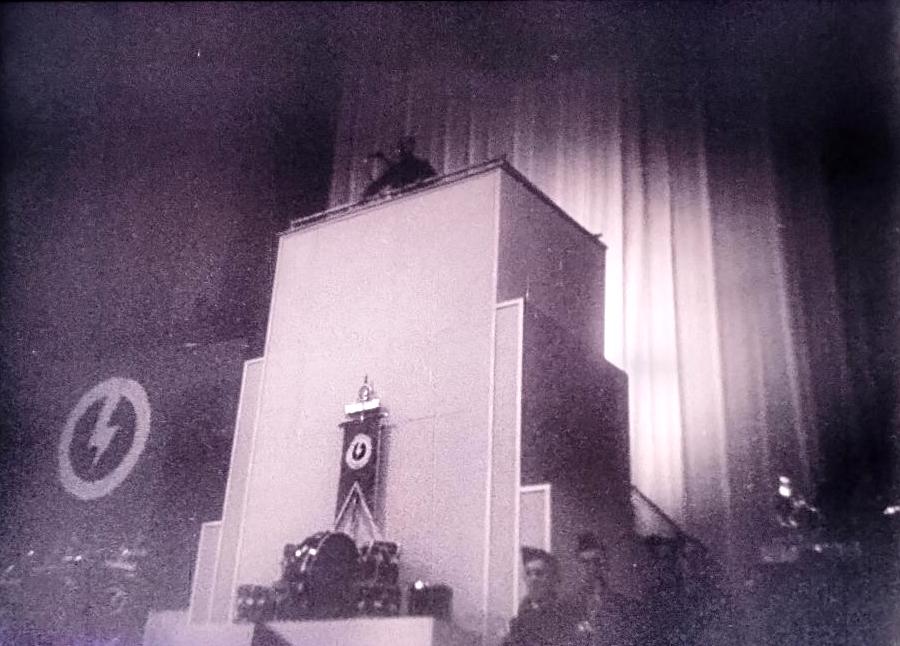

The rhythm of Crisis is determined by the Nazis both within and outside Czechoslovakia, and the reactions of the Czech government and its domestic allies. Guided by Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf, prominently displayed in the film’s second image, the followers of Konrad Heinlein’s Sudenten Party are portrayed as vicious agitators and propagandists who sew discontent among Czech German-speaking populations, openly advocating for Hitler, protected by the Czech Republic’s democratic freedoms they sought to undermine. The democratically-minded Czechs are seen as resilient fighters, willing to join with their French, British, and Russian allies to defeat Hitler, preparing for war during the May crisis, then mobilizing in August, psychologically crushed by their abandonment, especially by the French, with whom they shared a long tradition of cultural exchange.

Organizations like the left-wing Solidarity advocate for peaceful co-existence between the Republic’s various ethnic minorities. Through the eyes of a young female student, Mirka, we see Czechs bringing food packages to poor Sudenten Germans, staging cultural events for anti-Nazi German refugees, and promoting peace. Jiři (George) Voskovec and Jan Werich, the extremely popular leftwing cabaretists are seen explaining the English-French-Russian alliance with Czechoslovakia as the safety pin holding it together, and singing for a children’s event. Both artists fled to America.

But all Czech efforts are for naught when Chamberlain negotiates with Hitler without the participation of the Czechs, forcing President Beneš to resign. Crisis ends with an uncertain almost elegiac note with the sanctioned occupation of the border regions and the title: “Remember: Peace and freedom and the right to live – they can only be possible in lands where men are determined that the swastika shall not be raised in triumph…”

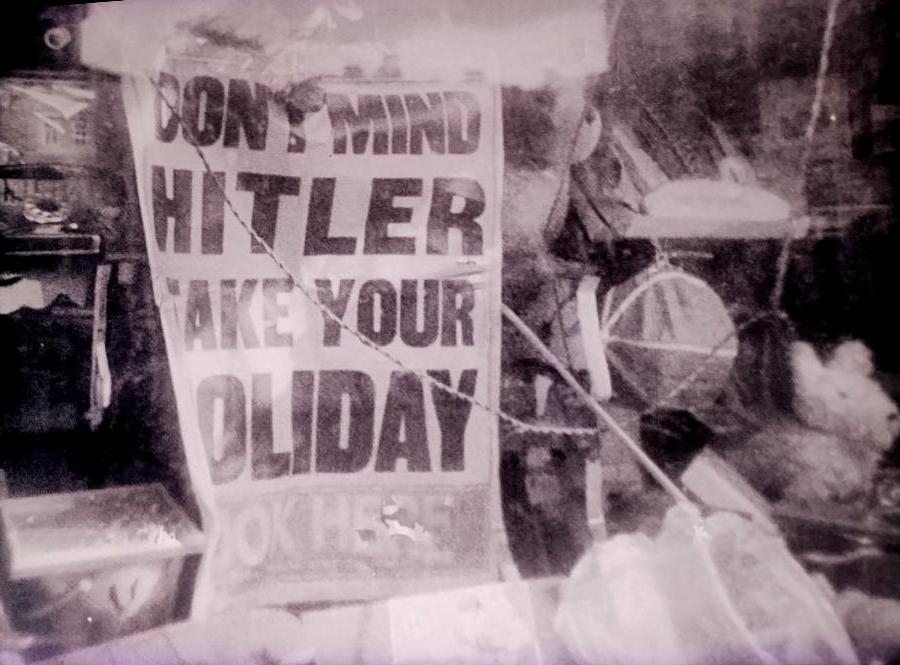

While Crisis focused on Czech resistance, Lights Out in Europe documents the failure on the part of the British and Polish governments to prepare seriously for war, choosing instead to nurture a false optimism that their people will remain out of harm’s way, even as Confessions of a Nazi Spy (1939) and boatloads of refugees warn Londoners of Nazi Germany’s intentions. Meanwhile, as in Czechoslovakia, Nazi Fifth Columnists destabilize the free state of Danzig, leading many Polish and German Jews to flee the city. Only after the invasion of Czechoslovakia in March 1939 did Poland begin securing its borders, while a general mobilization was only ordered in August, Poland’s generals confident they could withstand German tanks with cavalry and horse-drawn armaments.

Not surprisingly, the Hitler-Stalin Pact of 23 August is downplayed and the Soviet invasion of Poland from the East is not even mentioned, given Kline’s political sympathies. Similarly, the film ends shortly after the invasion of Poland, not with rousing cries for armed resistance, but with memories of the dead of World War I, as British soldiers return to the trenches of northern France: “Soldiers ask why war? Peace to end all war has never been tried.” With its focus on refugees, delayed social reforms, national paralysis, and WWI dead and wounded, the film is elegiac avant guerre.

For anyone interested in how German fascism divided and conquered its enemies, just as white nationalist Americans create divisions in our own democracy today, these two films should be required viewing. Beautifully restored, with audio commentaries by Thomas Doherty and Maria Elena de las Carreras, and other bonus materials, this Blu-ray set makes history palpable.

Somehow, my dad managed to finish his matura, only to be arrested in his freshman year at Prague’s Technical University by the Gestapo.

I can’t imagine a more terrifying event than to be arrested by the gestapo.

LikeLike