Archival Spaces 352

Meeting Leni Riefenstahl

Uploaded 26 July 2024

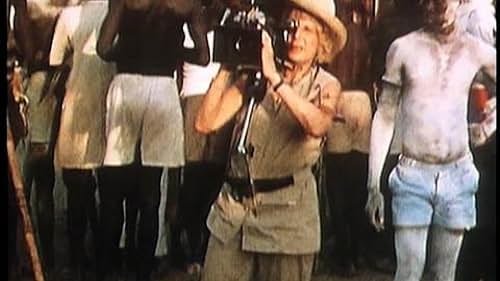

In March 1976, Robert Doherty, the Director of George Eastman Museum asked me to travel to New York to meet with Leni Riefenstahl, the infamous film director of Triumph of the Will (1935) and Olympia, Parts I and II (1938). At the time, Riefenstahl had recently published her photo book, The Last of the Nuba (1974), and was working on a new project of underwater sea life, Doherty was negotiating with her to acquire some original prints from both projects. She in turn had asked him to help her find the negative to the English-language version of Olympia, Pt. I, which had gone missing, and because I spoke German, Doherty thought I should meet her, even though I was only a post-graduate intern in the film department. After years of radio silence, Riefenstahl had again been in the news, causing controversy when she traveled to Los Angeles in September 1974 to receive an Award from Cinecon, while some (misinformed) feminist film critics lifted her onto their shields as an early woman filmmaker.

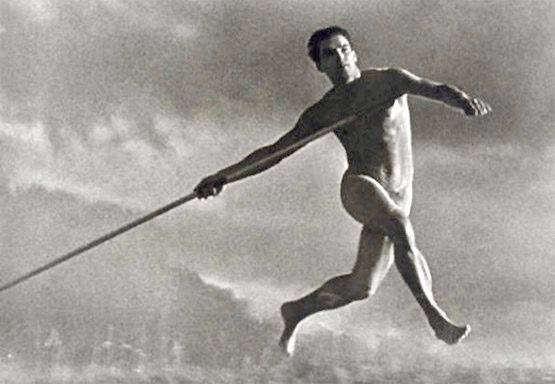

Riefenstahl was staying in a swanky apartment on Park Avenue, where I was ushered into a spacious living room with several original impressionist paintings on the wall. After introductions, she immediately proceeded to tell me how she had learned scuba diving at the age of 71, and how dangerous it had been to swim among sharks in the Caribbean, but that it was worth it because the images were so beautiful. I had not yet read Susan Sonntag’s devastating pan of her Nuba book, where she theorized that Leni had applied the same Fascist aesthetics to the seven-foot-plus Black Nuba bodies, as she had to Nazi Storm Troopers and Aryan athletes, but I intuitively maintained a healthy emotional distance, as a listened politely.

As Riefenstahl noted to me in a letter from 17 April 1976, she was most concerned about the whereabouts of her negatives, which she had sent to the Harvard-based filmmaker Robert Gardner more than a decade earlier who was planning to rerelease the film through his own distribution company, after he asked her to break her contract with McGraw-Hill. The negs had last been seen at WNET. She also hinted that she was looking for a permanent archival home for all her Olympia negatives because she didn’t trust the Germans who still treated her like a pariah, and was willing to ship them to Rochester if I found the missing negatives. I returned to Rochester, reported back to Doherty, and set about writing to film labs around the country, miraculously finding them in the MPL film lab in Memphis, Tennessee. After writing to Riefenstahl with the news, the negatives were shipped to Eastman, while the German negatives for Olympia arrived a short time later.

I thought that would be the end of it, but it wasn’t. Not even a year later, I was knocking on Riefenstahl’s Tengstrasse 20 door in Munich’s fashionable Schwabing district, recommendation in hand from my boss, James Card, who thought Leni could help. I had moved back to my parent’s home in Italy after my internship ended at GEM and was looking for work in Germany in the film business. I was ushered into her living room by Horst, her long-time secretary. Riefenstahl immediately began complaining that the Socialists had taken over Germany (actually the Social Democratic Party under Helmut Schmidt who was more of a liberal), and I quickly realized that under the veneer she was still a Nazi.

She couldn’t help me which was all for the best, since I’m sure a recommendation from her would not have been to my advantage, especially since some years later Nina Gladitz premiered her film, Time of Darkness and Silence (1982) on Riefenstahl’s utilization of Sinti and Roma during World War II for her fiction feature Tiefland(1943-54), who were then returned them to a concentration camp where they were murdered. (Riefenstahl sued and won, banning the Gladitz film for decades). Instead, I became a PhD. candidate in Münster, after interviewing for programs in Munich, Berlin, and Tübingen.

And I would talk to Riefenstahl yet again, almost two decades later. Having become Director of the Munich Filmmuseum in 1994, I negotiated the acquisition of the estate papers of Dr. Arnold Fanck with the proviso to curate a retrospective exhibition. Fanck had not only been the inventor of the German “mountain’ film but had given the minimally talented dancer Riefenstahl her first film role in The Holy Mountain (1925), then cast her in four more films, including The White Hell of Piz Palü (1929). By the 1940s, though, the tables had been turned. Fanck was out of work because Goebbels hated him, so Riefenstahl hired Fanck to make a series of short documentaries on Nazi artists like Arno Brecker and Josef Thorak for her production company. Given her close relationship with Hitler, she retained the rights to all her work, despite the violent objections of the Propaganda Minister, keeping them after the war, while almost all other Nazi films passed into the hands of the German government via the UFA.

In order to screen Fanck’s last films in the exhibition, I had to get permission from Riefenstahl and Horst, who was still working for her. She did give us screening rights but charged the Museum a hefty fee. I can’t say I shed any tears when she died at the age of 101 in September 2003, again proving that evil often survives when the good die young.

One of your best; I’m glad you included your editorial opinion of her and strayed from strict reportage.

-marty

Marty Cooper

President

Cooper Communications

16000 Ventura Blvd.

Suite 1000

Encino, CA 91436

Direct: 818-359-0231

LikeLike

Thanks, Chris for posting this film history! I hope after helping Reifenstahl locate those long-lost negatives for Olympia Pt1, Reifenstahl at least enrolled you on her Christmas card list. She reminds me of another great filmmaker D W Griffith who was a racist.

Had the film history class at the U of D known that one of our classmates would meet such a famous filmmaker, you would have become an instant celebrity.

LikeLike

Thanks, Joe. It wasn’t until Barrett’s class that I even knew who Riefenstahl was.

LikeLike