Archival Spaces 350

Spanish-Language Cinema Hollywood, 1929-39

Uploaded 28 June 2024

Back in 2017, I organized a major Getty-funded exhibition, Recuerdos de un cine en español: Latin American Cinema in Los Angeles, 1930-1960,” with the help of my co-curators, Maria Elena de las Carreras, Colin Gunkel, and Alejandra Espasande-Bouza, which presented forty-one films from Hollywood, Mexico, Argentina, Cuba, and Puerto Rico; almost all of them had been screened in L.A. first run theatres at the time of their release. We programmed the films at the Hammer and the Downtown Independent, the last physical remains of a circuit of cinemas, catering to Latinx audiences. Augmenting UCLA’s exhibition catalog were two book publications, Cinema Between Latin America and Los Angeles. Origins to 1960 (2019), and Hollywood Goes Latin. Spanish-Language Filmmaking in Los Angeles (2019). Alejandra Espasande-Bouza’s important essay appeared in the second volume but also contributed valuable ideas to the curatorial team, especially her expertise in Cuban cinema. She has now organized a wall exhibit, Hablada en Español. The Legacy of Hollywood’s Spanish-Language Cinema (1929-1939) is on view for only three more days at L.A.’s Pico House, one of the few original structures in the heart of what was once the thriving Mexican community up and down Main Street.

Last week, I received an invitation to attend a screening of the restored version of Carlos Gardel’s El día que me quieras (1935), his second to last film before tragically dying in a mid-air plane over Medellin, Columbia. It was the third program, after screenings earlier in the month of the Spanish-language Drácula (1931) and The Spanish Dancer (1923). Maria Elena de las Carreras introduced the film, which was screened in a side gallery of the exhibit. Afterward, Maria Elena, Alejandra, and I participated in a Q & A. followed by a live Tango singer performing, while visitors roamed through the exhibit.

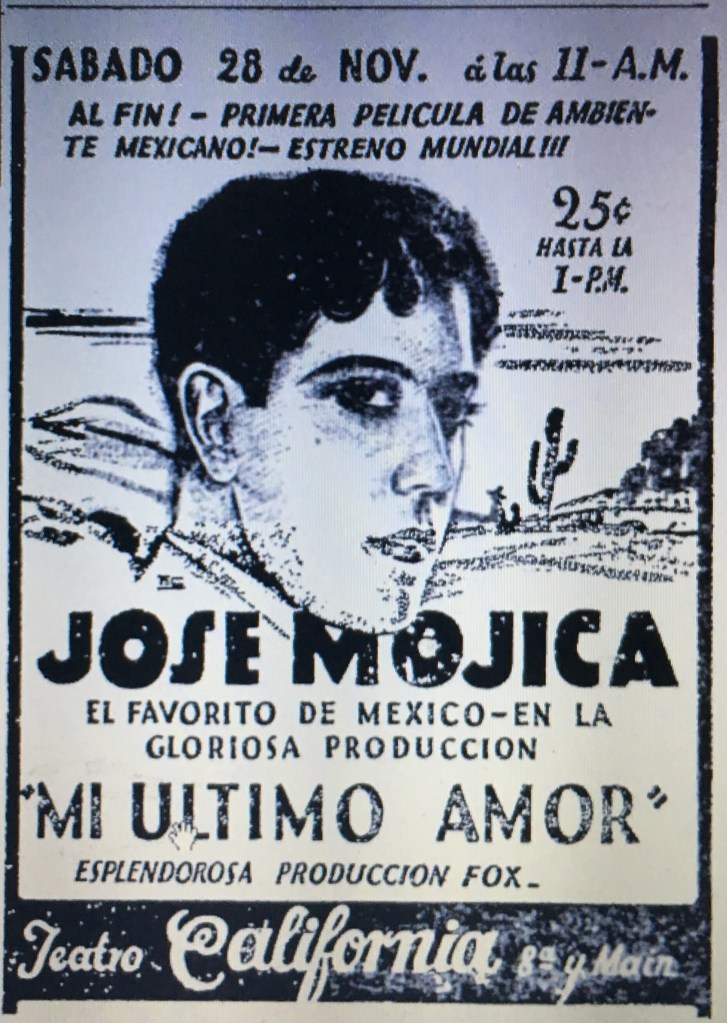

As Espasande-Bouza notes in her introductory text: “The materials on exhibition bear witness to a cinema on the brink of extinction that was once a daily staple of the vibrant movie-going experience enjoyed by Angelenos throughout the 1930s.” She further notes that of the approximately 180 Spanish-language films produced in Hollywood by the majors and studio independents, less than 10% exist in film archives, and only 2% are available on electronic media. Through posters, film stills, production shots, fan magazines, and film star portraits, this exhibition brings back to historical consciousness a cinema perdu, an American cinema in Spanish, produced for the sizable domestic market, all of Latin America, and Spain. Spanish Hollywood’s material culture, at least that which survives, despite its worldwide circulation, its artifacts in many cases represent the sole visual record of a film. It is a plea for preservation and accessibility.

Gardel is represented in Hablada en Español with a video monitor screening clips of his singing performances in Asi Cantaba Carlos Gardel, as well as in photo portraits. However, the most interesting exhibition pieces are of lost films. For Example, the production crew and cast photo of Dos Noches (1933, Carlos Borocosque) . a Spanish=Language version of the B-film Mayfair Studio production, Revenge of Monte Carlo (1933, B. “Breezy” Reaves Eason), starring Spanish film star José Crespo in both versions, while popular Conchita Montenegro, another star from Spain, played in the Spanish version, June Collyer taking her role in the English version. Montenegro is also represented with a cover image from the Madrid-based fan magazine, Cinegramas (1934-38). Both versions were produced by Fanchon Royer Pictures, controlled by female producer Fanchon Royer. The Chilean film director, Carlos Borocosque, who directed mostly Spanish language versions for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, before moving to Argentina, where his work helped establish the Argentine film industry, was not only responsible for Dos Noches but also an important correspondent for Latin American fan magazines; he is represented in the exhibition by an official studio portrait.

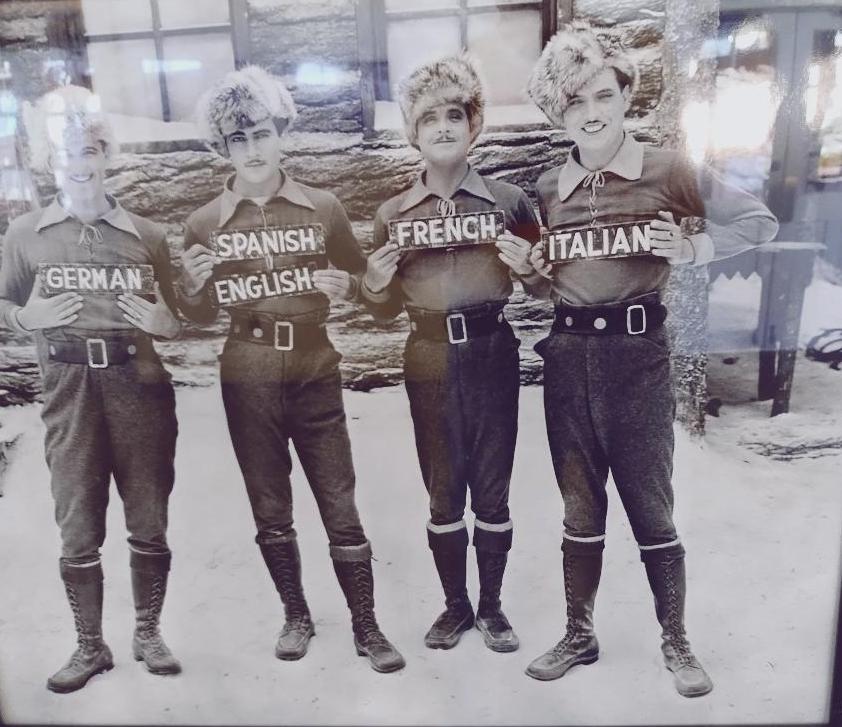

Another great photograph depicts in costume the four actors, playing Louis le Bey aka Monsieur le Fox in five different language versions of Hal Roach Studio’s Men of the North/Monsieur Le Fox (1930): in German with John Reinhardt, in Spanish and English with Gilbert Roland, in French with Anré Luguet, and in Italian with Franco Corsaro. Except for the English version, none of the other versions unfortunately survive. Indeed, the survival rate of various language versions, produced by Hollywood is dismal.

The most famous Spanish-language version of a Hollywood film is, of course, Drácula (1930), starring Carlos Villarias in the Bela Lugosi role. With Lupita Tovar, Drácula en espagñol is sexier than the American version but its present popularity and circulation on DVD is the result of a film restoration in the 1990s by Bob Gitt at UCLA. The exhibition’s lead image is of Villarias, a second photo later is complemented by an extremely rare booklet, Spanish Casting Directory, published in February 1931, which was probably instrumental in finding actors for the Universal production. Tovar, BTW, lived to be 106 years old and is the grandmother of film directors Paul and Chris Weitz.

This exhibition is well worth a visit. Hopefully, more films from Spanish Hollywood will be released on video, allowing the public to rediscover Carlos Gardel, José Mojica, Antonio Morena, Ramón Novarro, Lupe Vélez, Lupita Tovar, and Conchita Montenegro.

Thanks for this. Although I took some classes in film history in college, I can’t recall it being mentioned Hollywood produced spanish language films. I had assumed those films had been produced in Mexico.

LikeLike