Archival Spaces 349

UFA greets Lubitsch: Early Sound Film Operettas

Uploaded 14 June 2024

In November 2023, I gave a keynote, titled “UFA greets Lubitsch,” at Cinegraph’s annual film historical symposium, “Danger! Music…Between Film Comedy and Musical.” My Archival Spaces 336 discussed their film program of Weimar German sound films, which included many discoveries of recent restorations. Now my paper will be published in German by the Hamburg Cinegraph film research center, headed by Hans-Michael Bock, with Erika Wottrich no second fiddle.

I recently discovered on YouTube a Joseph Schmidt film, When You Are Young, the World Belongs to You (1934), which I had not seen before writing my essay that mentioned Schmidt’s previous film, My Song Goes Round the World (1933). That film premiered in Berlin’s largest cinema on 9 May 1933, days after the Nazis burned books, and weeks after the Jewish boycott began, actions that would lead to the forced emigration of more than 500 blacklisted Jewish filmmakers. Richard Oswald who directed both films, shot the later film in Austrian exile, then fled to Amsterdam and Paris, before ending in Hollywood, where his career crashed and burned. In both films the diminutive opera and recording star played characters who come from humble beginnings but become singing stars while losing the girl to a friend. In Young, an Italian gardener-opera star, Carlo, suffers from unrequited love for his wealthy childhood girlfriend, while his relationship with his mother is deeply oedipal, and his friendship with the faithful Beppo, played with comic flair by Szöke “Cuddles” Szakall, is possibly gay. As in Song, Oswald creates numerous situations in Young, which allow Schmidt to perform on stage or in stage-like situations, thus mitigating the irritation characters bursting into song in a realistic narrative. As a recording star, Schmidt’s voice was recognizable to millions of fans, so Oswald highlights the inter-media aspects of opera: Carlo sings to his mother on the phone, and competes with his own voice on a record player, to prove he is who he is. Repeatedly, his voice is disembodied, as in the extended travelogue footage of the singer’s stops in Paris, Amsterdam, New York, and Vienna. That willingness to self-reflexively meditate on film craft through experimental forms characterized early German film operettas and Ernst Lubitsch’s comedic operettas at Paramount.

An irony of the history of German sound film operettas is that at the very moment the Ufa-produced films celebrated their first popular successes, the classic Viennese operetta had lost much of its popularity, even on Broadway where it had reigned supreme for almost forty years. Operettas migrated to the cinema after the perfection of sound film technology, becoming an ever-shifting genre in Berlin and Hollywood, guided by its own conventions and form. Operettas also migrated to the new medium of radio (and disc), becoming the most requested form of popular music in a 1926 radio survey. However, unlike the radio which only acoustically reproduced stage operettas, as did recorded discs, filmmakers found creative visual solutions to marry image and sound. In his ground-breaking book on German musicals, Michael Wedel discovers the formal richness of early film operettas in the joy of technical experimentation, and in film economic imperatives, based on alliances with the broadcasting and record businesses.

UFA sound film operettas resisted classical narratives, based on coherent and logical plots, psychological motivation of its characters, and identification mechanisms that bound the audience to the story. Similarly, Paramount‘s film operettas by Ernst Lubitsch and Rouben Mamoulian eschewed film realism. Especially Maurice Chevalier and Jeanette MacDonald’s films, like The Love Parade (1930, Ernst Lubitsch), Love Me Tonight (1931, Rouben Mamoulian), and One Hour With You (1932, Ernst Lubitsch), displayed a high degree of self-reflexivity, employed direct address, utilized both song and dance to move the plot forward, and emphasized the artificiality of their never-neverland settings in a mythical Europe of royalty, where romance consistently overcame class difference.

In contrast, the UFA operettas, whether Three Good Friends (1930, William Thiele) or A Blonde Dream (1932, Paul Martin) were firmly situated in real locations, like gas stations and trailer parks, while The Congress Dances (1931) ends with the Prince and the flower girl going their separate ways because class difference is unsurmountable. As if to confirm the trans-Atlantic affinity between Berlin and Hollywood’s operettas, Ludwig Berger included film operetta scenes in I By Day, You by Night (1932), which consciously parody Lubitsch’s films. Berger inserted these scenes on a film screen – the singer Ursula van Diem looks just like MacDonald – , introduced and commented on by a working-class film projectionist. The film within film scenes are preceded by fireworks, again creating a self-reflexive moment, while the working class love story outside the cinema is contrasted to the fantasy narrative in the cinema.

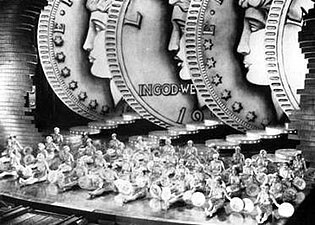

Because the artificiality of Paramount’s Ruritanian dreams alienated Depression-stressed audiences, the most working class of the Hollywood studios, Warner Brothers, introduced the backstage musical, e.g. 42nd Street (1933, Lloyd Bacon), Gold Diggers of 1933 (1933, Mervyn LeRoy) and Footlight Parade (133, Lloyd Bacon), whose plots were situated on Broadway, thus creating a realistic motivation for songs and dance on stage, while metaphorically addressing the effects of the Depression.

The German counterpart to the backstage musical was the fictitious film biographies of 1930-34. Michael Wedel notes that these films with singing stars Richard Tauber, Joseph Schmidt, Gitta Alpar, and Martha Eggerth, presented their songs and arias on improvised or actual stages, while the rise to stardom mirrored the singer’s actual biography. In contrast to the Hollywood backstage musical, though, the male singers in Berlin often sacrifice romance for their careers, as in the two Joseph Schmidt films.

Surprisingly, the backstage musical’s popularity also waned quickly in America, supplanted by a comeback of the film operetta, no longer self-reflexive, as with Lubitsch, but rather film adaptations of classical operettas by Victor Herbert and Sig Romberg, often mixed with other genres. Jeanette MacDonald moved to MGM, where she was teamed with Nelson Eddy and starred in Rose Marie (1936, W.S. van Dyke), Rudolf Friml’s operetta from 1924, which mashed up backstage musical, western, and melodrama.

Meanwhile, despite the objections of Joseph Goebbels to the “Jewish” film operetta, the UFA continued to produce operettas, especially with Martha Eggerth, who was allowed to perform in the Third Reich though Jewish, even if the films were actually shot in Austria and financed by Jewish producers. Like the MacDonald/Eddy films, they were adaptations of Franz Lehar and other classical operettas, mixed with different genres.

Although no historian to my knowledge has made such a comparison, it does therefore seem fruitful to compare the historical development of film operettas/musicals in Berlin and Hollywood in a trans-Atlantic context. Such a comparison may also reveal why exiled German directors, like William Thiele, Joe May, and Erik Charell failed, when they made their first operettas in Hollywood.