Archival Spaces 347

Bushman (1971/2023) rediscovered

Uploaded 17 May 2024

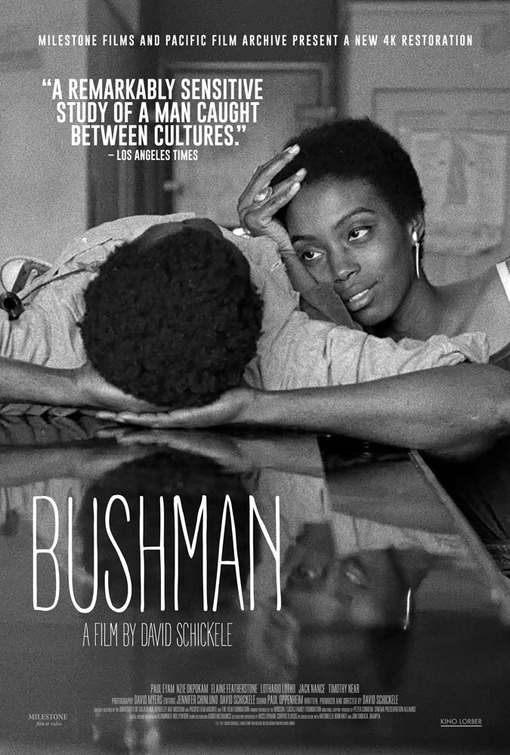

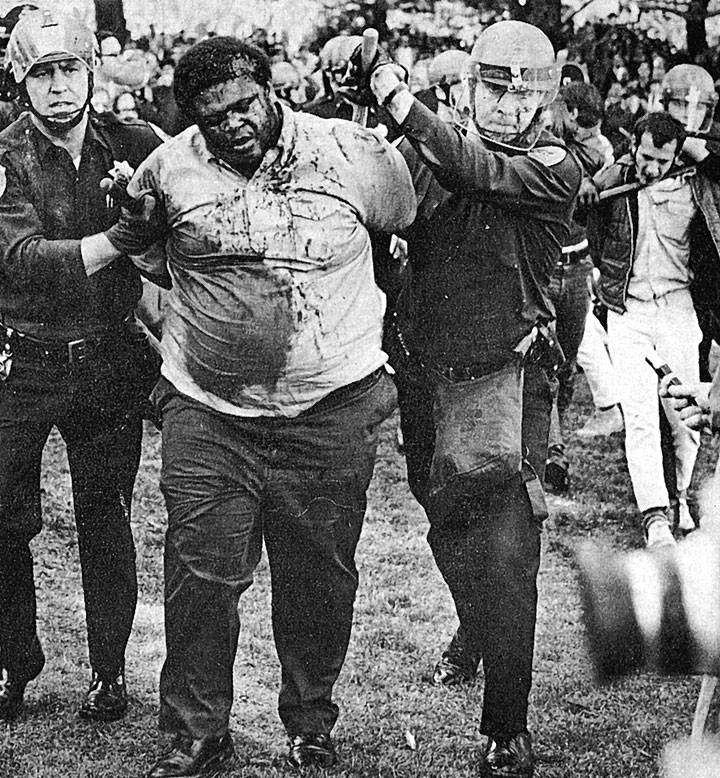

Milestone and Kino Lorber are releasing a Blu-ray of a new restoration of Bushman (1971) on 21 May 2024, a film that was not exactly overlooked when it first screened – it was praised by critics – but it never found a distributor. Directed by David Schickele, a Peace Corps veteran who had previously helmed a documentary about his service in Nigeria, the film visualizes the fate of a Nigerian Exchange Student/Lecturer. The restored Bushman, is attracting a lot of deserved media attention. Not only is the film now available on Kanopy, but it was the subject of an NPR story a few days ago; rare for an old film. The film is indeed timely, Bushman’s star, a Nigerian language instructor at San Francisco State, Paul Eyam Nzie Okpokam, was deported while the film was in production, the victim of an overtly racist police force, hell-bent on finding a scapegoat for their own shortcomings during the infamous 1968 student demonstrations at SFS. Flash forward to this Spring’s student actions against genocide in Gaza and the police response – the first nationwide college upheavals in fifty years – and the continuing mistreatment of persons of color at our borders and the film is more than topical.

Due to the arrest of its subject, before eventual deportation, Bushman could not be completed until 1971, its falsely accused star only visible in the film’s final section in surreptitiously taken photographs at his farewell. Not surprising that it took Schickele more than two years to salvage his project. The film opened at various film festivals, including winning the Gold Hugo for Best First Feature at the Chicago Film Festival, then screening at the San Francisco, Filmex Los Angeles, Dallas, Atlanta, Washington AFI, London, Venice, and Adelaide Film Festivals. It also received glowing reviews from the likes of Albert Johnson, Roger Ebert, and Roger Greenspun, all of them agreeing on the film’s ability to communicate racial injustice through experimental film forms rather than ideological polemics.

However, before I go on, I want to mention the restoration, financed by the Film Foundation and the Pacific Film Archives in the Berkeley Art Museum. The film’s lush black & white cinematography sparkles in Ross Lippmann’s digital restoration, made from the original 35 mm negatives, housed at BAMPFA. Lippmann also oversaw UCLA’s restoration of Charles Burnett’s Killer of Sheep (1977), another 1970s independent Black film that exposed the everyday racism of American society but did not find a distributor until 2006 when Milestone released the restoration. Thanks to Amy Heller and Dennis Doros at Milestone Films, the availability of independent African-American cinema in that period has expanded significantly, including numerous L.A. Rebellion titles, as well as East Coast examples, like Kathleen Collins’ Losing Ground (1982/2026).

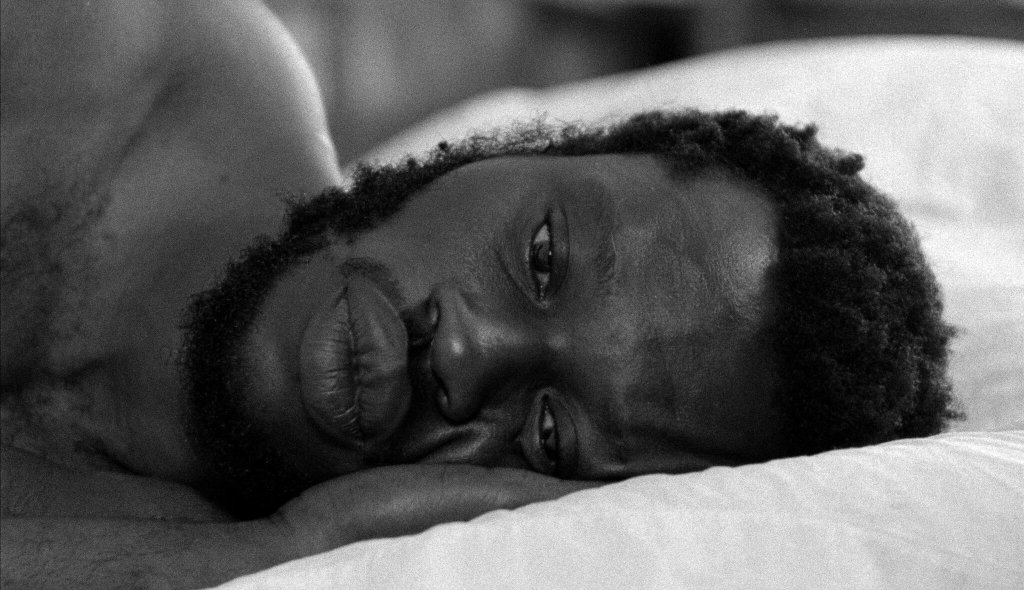

Bushman opens with a text: “1968: Martin Luther King, Robert Kennedy, and Bobby Hutton are among the recent dead. In Nigeria, the Civil War is entering its second year with no end in sight.” This dual focus on the USA and Nigeria is maintained through the rest of the film, first via a first-person narration (on camera and off) of the hero’s life in Nigeria, before coming to San Francisco, and through images that cut back and forth between documentary shots of Nigeria, and the fictional Gabriel, meeting up with friends and girlfriends, trying to find a job, dabbling in black power politics, but essentially maintaining the same distance he had to his Catholic education. He is constantly subjected to subtle often unconscious forms of racism, from the guy who gives him a ride on his motorcycle and obsesses over bare-breasted African women, to the white women for whom he is a charity case and exotic trophy. Later, Gabriel looks for a job, but misunderstands a personal ad and ends up in the flat of a gay man hoping to have sex. Interestingly, Schickele juxtaposes Gabriel/Paul’s self-aware narration with his passive and virtually silent interactions with his mostly alien environment. The director intercuts images of the streets of Oakland with images of Nigeria, whereby at times it’s hard to identify which is which.

The fragmentation of the film’s first hour is heightened in its last 15 minutes when overt American racism destroys Gabriel/Paul’s life in the wake of student demonstrations on campus. The San Francisco State student strikes from November 1968 to March 1969, involved a wide coalition of progressive California advocacy groups, representing Black, Asian, Latino, and Pacific Islander interests, demonstrating for ethnic studies and more inclusionary university politics. Schickele filmed the college’s student demonstrations and violent police brutality, which he incorporates into the film, before having various witnesses report that Paul Okpokam was literally framed, after being forced to accompany two plainclothes detectives into a men’s room where they try to give him a bomb, subsequently branding him a terrorist, and sending him to San Quentin. Back in Nigeria, Paul Okpokam became a published playwright, theater director, and teacher.

Through its experimental form and elliptical narrative, Bushman forces the viewer to not only actively piece together the fate of Gabriel/Paul and its consequences, but also confront the racism that is still endemic to American society then and now.

<

div dir=”ltr”>Fascinating, impeccably and luminously written as always Chris! Your breadth of research is impressive

LikeLike

Thanks, Freida!

LikeLike

Illustration

LikeLike