Archival Spaces 337

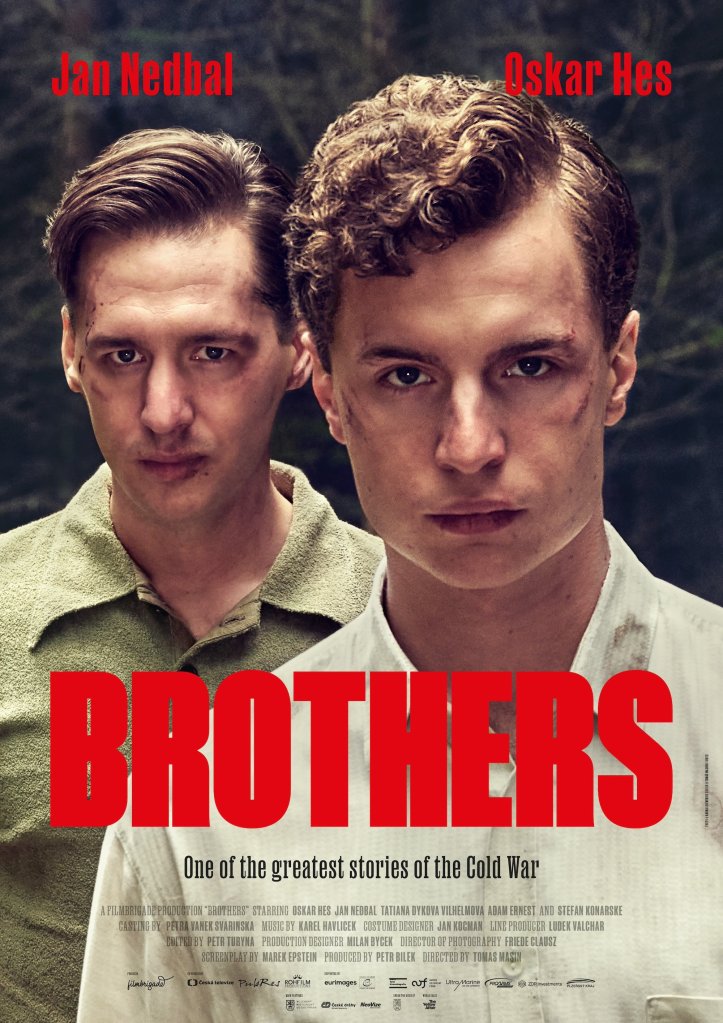

Bratři / Brothers (2023, Tomáš Mašín)

Uploaded 15 December 2023

Ambassador Jaroslav Olša and the Czech Consulate in Los Angeles recently invited guests to a special screening of the Czech entry to the Academy Awards, Bratři / Brothers (2023, Tomáš Mašín), at the Crescent Theater in Beverly Hills with the director in attendance. The film opened in Prague in October. Like several recent films coming out of the Czech Republic, including In the Shadow (2012), Milada (2017), and The Golden Sting (2018), Brothers addresses the dark days in the 1950s of Czechoslovakia’s Stalinist dictatorship under Klement Gottwald, when the Státní bezpečnost, the secret police, ruthlessly suppressed all opposition. The film was of interest to me, not only because my father, Jarome V. Horak, was sentenced to 20 years hard labor in absentia, for his role in the „abduction“ of Dr. Petr Zenkl (https://www.cinema.ucla.edu/blogs/ archival-spaces/2018/08/31/abduction-petr-zenkl), but also because my aunt and a cousin were imprisoned for years by the Communists. My aunt‘s husband, Gen. Josef Kohoutek, was executed on 19 August 1942 at Plötzensee (Berlin) by the Nazis (https://wordpress.com/post/archivalspaces.com/1945), in direct reprisal for Reinhard Heydrich’s assassination, just as Josef Mašín, leader of the Three Kings anti-Nazi resistance group was executed on 30 June 1942 in Pankrác Prison (Prague) weeks after Heydrich’s death.

Mašín’s film begins with the execution of Josef Mašín after intense interrogation, then relates the story of his two sons, Ctirad (called Radek) and Josef Mašín, who in 1953 became resistance fighters against the Communist dictatorship; they were perceived as blood-thirsty terrorists by others. Their legacy is even today, seventy years later, hotly contested in the Czech Republic, which is why the director, “a distant relative” spent ten years trying to get the film made

The brothers, who were still students, aged 21 and 23, initially planned to form a resistance cell, after reading that they could join the American army to overthrow the Communist government. With school friends they make plans to escape to West Berlin, first agreeing to steal weapons from a local police station. But being amateurs, their plans go completely wrong, and in September 1951 they kill a local policeman without getting any weapons. In a second raid on another village police station, they do get a cache of weapons, but they kill a second policeman in cold blood after being handcuffed and drugged. Later, in robbing a payroll car to finance their escape, they murder a civilian. Their plan to flee the country is upended when the secret police capture one of the conspirators, and the older brother is sentenced to two years hard labor in a uranium mine (possibly the same mine in which my cousin, Pepic was incarcerated), the police not connecting the police station raids to the group. Meanwhile, their mother, who has stomach cancer is forced out of her home and eventually imprisoned.

After Radek’s release, thanks to an amnesty following Stalin’s death in 1953, the group fled across the border into East Germany, where they were involved in a shoot-out at a train station, killing several Volkspolizisten. Despite a massive manhunt involving thousands of East German police and the Soviet Red Army, the two brothers and a friend eventually make it to West Berlin, while the remainder of the group is sent back to Czechoslovakia, where they are executed, while almost everyone who knew the group is mercilessly harassed, the mother dying in prison without treatment.

The film makes clear that the brothers have taken the words of their father to heart to fight tyranny because to live without freedom is to not live at all. But beyond that, the audience learns little about their inner motivation, only seeing their actions. The film does a good job of visualizing the absolute oppressiveness of the Stalinist era and the ruthlessness of the secret police. In a time when few Czechs attempted any kind of resistance, the Mašín group is portrayed as heroes. The latter half of the film actually morphs into a thriller, as the group escape after being surrounded by hundreds of German police. But there is also a moral ambiguity here, in particular when Josef Mašín slits the throat of an unarmed, handcuffed country policeman. The killing is not actually shown, just as their killing of the innocent civilian during a car-jacking remains off camera, so the director is staking the deck to an extent.

Until I started doing some research, I was unaware of the degree to which the Mašín Brothers are still controversial in the Czech Republic. After their successful escape, the Communists branded them as terrorists and murderers, and for many in the country that label has stuck. Even after the Velvet Revolution in 1989, when many victims of the Communist regime were rehabilitated, President Václav Havel and other government officials kept their distance, because 55% of the Czech public (according to a survey in 2003) still considered them murderers. Their criminal case was in fact not removed from the books until 2001.

It is unclear from Czech film reviews, whether this film will in fact change anyone’s mind about the brother’s legacy since opinions are still divided on their actions. However, Tomáš Mašín has made a gripping film that does illuminate the terrible crimes committed by the Gottwald regime, and the, at times, wrong-headed attempts to fight that tyranny.

Very well written film review! I’m glad my grandparents left Eastern Europe because in WW2 they would have been victims of the Nazis and Communists marching through their country (Lithuania).

LikeLike