Archival Spaces 335

Alfred Zeisler

Uploaded 24 November 2023

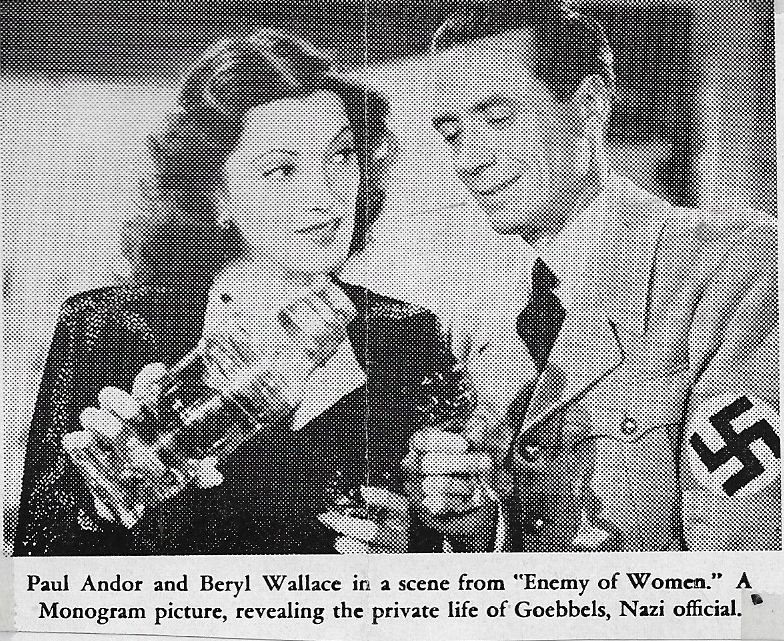

I first interviewed Alfred Zeisler in April 1983, when he attended a Berlinale Retrospective; I was in the final throws of writing my dissertation which included a chapter on Zeisler’s biopic of Dr. Joseph Paul Goebbels, Enemy of Women (1944). Zeisler had been a powerful producer at UFA, heading one of four production units, along with Erich Pommer, Bruno Duday, and Günter Stapenhorst. Unlike many German émigrés, Zeisler was seemingly not Jewish, because he continued working in Germany until at least 1935, having been born an American citizen. Why had he left? Zeisler hinted it was political because he and Goebbels had crossed swords. Surprisingly, no files for Zeisler were to be found at the Berlin Document Center (now Bundesarchiv), where all Nazi Party documents are archived. I’ve now returned to my Zeisler research by writing an article on his popular detective films.

Henry Alfred Zeisler was born in Chicago on 26 September 1892. His father, Moritz Zeisler, born in Moravia, Austro-Hungary, in 1856, and was Jewish, the family was probably originally from the Ukraine. Moritz Zeisler was an actor, who spent at least two years in America, acting on German language stages in New York and Chicago, where he played middle-aged character parts. Alfred’s mother, Metha E. Engelbrecht, was born around 1870 in Austria. The family moved back to Berlin in May 1894, when Moritz Zeisler joined the company of the Königliches Schauspielhaus (Royal Theatre), while little Henry attended school in Berlin-Charlottenburg.

Zeisler was eighteen when his father died, so he followed in his father’s footsteps, a journeyman actor in Zwickau, Berlin, Vienna, and Prague over the next ten years. He returned to Berlin in 1921, having made up his mind to work in the film industry, since his acting career was not going anywhere fast. Through Albert Pommer, Erich’s brother, he got a job as a production assistant at UFA for Fritz Lang’s Destiny (1921), but quickly moved on to the Harry Piel Film Company, writing three detective-adventure films for the producer-director-actor. In writing crime scripts for Piel, Zeisler learned the craft from one of the best, setting Zeisler on his future path as a crime specialist.

By the mid-1920s Zeisler was working as a successful producer for the Deulig Company, then moved back to UFA in the same capacity in 1927. However, Zeisler’s biggest successes came with the coming of sound. He directed and produced Der Schuβ im Tonfilmatelier/Shot in the Film Studio (1930), a murder mystery, which was a commercial and critical success; in it, Zeisler’s police detective actually solves the crime using sound film technology. Zeisler received a bonus, because he had in his hyphenated role brought the film in far under budget. His next crime drama, Express 13 (1931) featured night scenes on location – a first – and involved an attempted assassination on a night train. With his crime film Der Schuβ im Morgengrauen/Shot at Dawn (1932), Zeisler became the golden boy at UFA, having shot German and French language versions simultaneously for the price of one film. Thus, in Spring 1932 he was made head of his own production unit, and in 1935 Zeisler named production head for the whole studio.

Why Zeisler chose to emigrate in September 1935 is not completely clear since his Dutch wife, Lien Dyers, was a film star at the studio and she had to give up a flowering career. One can assume that as an American citizen, Zeisler was not forced to prove his Aryan lineage, so the Nazis might not have known his father was Jewish (in their eyes) or was he allowed to work, despite being “Half-Jewish,” like Reinhold Schünzel or company executive Hugo Corell? Zeisler recalled that the Gestapo searched his offices at UFA, because an illegal anti-Nazi publication, Das Braunbuch (1934), which uncovered the truth about the Reichstag’s fire, was circulating on the lot. Zeisler said he not only read it but was involved in a resistance cell. Apparently, Goebbels also hated Zeisler, so he asked Ludwig Klitsch, his boss at UFA, to take a leave of absence to produce a film in London. On the other hand, Zeisler’s grandson, Dillon Beresford reports, Zeisler had confessed to his daughter that he was working as a spy for the Soviet Union, given he knew Hitler personally and had access to information. In Hollywood rumors surfaced he was a Communist, complicating his American career and making him a constant FBI target, leading ultimately to him losing his US citizenship.

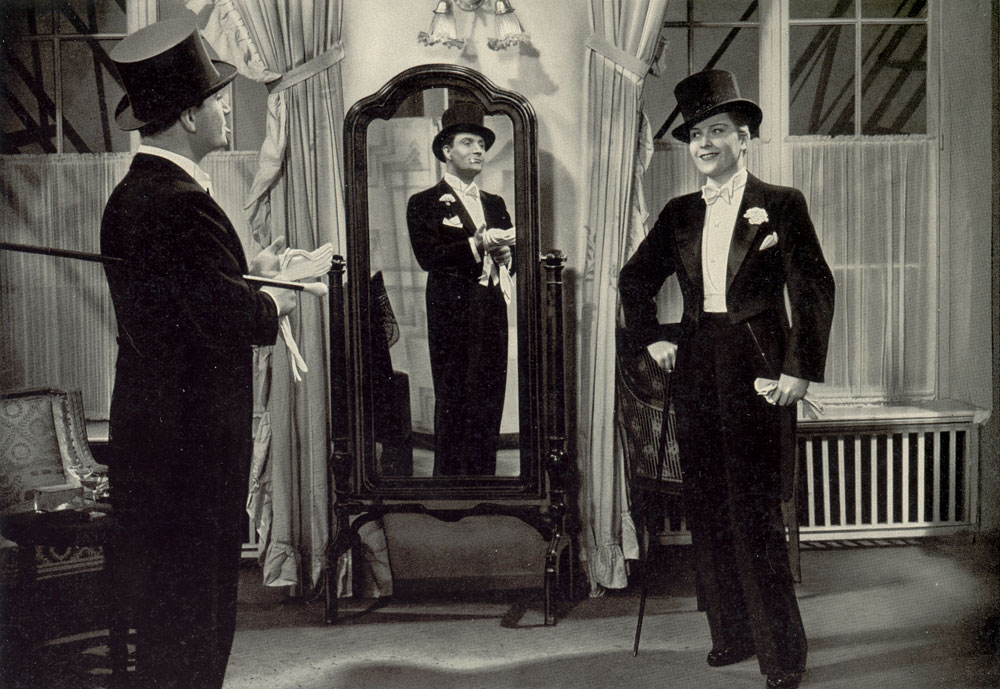

Once in England, Zeisler teamed up with the émigré producer Otto Klement to direct The Amazing Quest of Mr. Ernest Bliss (1936) with Cary Grant. After two more films, Zeisler and Dyers moved to Hollywood in October 1937. But neither he nor his wife had any luck. They would soon divorce and he would not direct again until 1943, when he produced Enemy of Women, which was cut by 50 minutes by the distributor, turning a serious biography into an exploitation film. He then directed three very low-budget crime dramas for Monogram and Eagle-Lion, including Fear (1945) a well-reviewed adaptation of Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment. After a few minor acting gigs, Zeisler called it quits. Exile had not been kind to him.